by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

Maybe this is something that happens when you reach a certain age?

But lately, I’ve found myself yearning to revisit things like paintings and books. Ones I loved when I was young. Like standing before Raphael’s Madonna del Cardellino in the Uffizi again. I was nineteen when I first saw the picture. Viewing it again thirty years later, I asked myself: How has the painting changed? How has the viewer changed? Am I even the same woman now? Or maybe it is the world that has moved on….

It was not long after seeing the Raphael that I first read Moby Dick. A philosophy major at Berkeley, I read Melville’s novel in a class taught by world-renown Heidegger scholar Hubert Dreyfus. The class, was called “Man, God, and Society in Western Literature” and Moby Dick was the last work on the syllabus, after reading Homer, Virgil, and Dante. Indeed, it was the culmination of the class.

The greatest book of American literature ever written, Professor Dreyfus told us this again and again.

Call me Ishmael.

God, I loved that first sentence… But it was the rest of that opening paragraph that really grabbed and shook me. That same one about which Ta-Nehisi Coates judged to be “the greatest paragraph in any work of fiction at any point, in all of history. And not just human history, but galactic and extraterrestrial history too…” Here it is:

Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen, and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.

The words exert the same power over my imagination now as they did back then when I was nineteen. Re-reading the novel this year, as I am also consulting several other books about Moby Dick, I learned that nowadays people consider that Ishmael was depressed and maybe even suicidal during that dark and drizzly November of his soul.

But back when I was nineteen, I didn’t think of it like that. Quite the opposite, in fact. I thought Ishmael was a kind of kindred spirit. Like me, he was someone who wanted to be free. Not suicidal. He simply resisted being made to jump through the hoops demanded by society: to make money and get married. Have a mortgage, pay taxes…. No wonder he wanted to knock people’s hats off their heads. Back then, so did I. Less depressed than he was frustrated and wanting to just get out there and see the world.

And luckily for Ishmael, by the end of the opening chapter of the novel, he had found his soul mate and was off with Queequeg on a great adventure:

By reason of these things, then, the whaling voyage was welcome; the great flood-gates of the wonder-world swung open, and in the wild conceits that swayed me to my purpose, two and two there floated into my inmost soul, endless processions of the whale, and, most of them all, one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.

I had similar feelings, which soon led me to voyage out into the world at twenty-one, not returning back to the US for over two decades. To live big and see the world.

I was reminded of this watching an interview on 60 Minutes Australia with a Cape Cod lobster diver Michael Packard, who managed to find himself caught up in the mouth of a humpback. Tumbling around inside in there, until the whale finally spit him out, the experience led him to take stock of his life. In the interview he remarked how he felt bad for getting in the whale’s way and spoke movingly about how grateful he was to have gotten out alive—back to his family and the ocean he loves so much. Packard explained that he had never wanted an ordinary life. He yearned to be out in the wonder-world, living a life of adventure—and for him, like Ishmael, that meant the sea.

2.

2.

Something else that I missed completely in my youthful reading of Moby Dick: that Ishmael, in finding his soulmate in the “cannibal” Queequeg —and in comparing their affectionate relations to that of marriage— was noteworthy in his open-minded tolerance and cosmopolitanism. Such a sweet show of love and friendship—how did I ever miss it?

Melville was open to the world across the oceans, curious about distant cultures and languages. But he was also drawn to the confusing world that exists between people. I would come to understand this in my new home, in Japan, where “people” is written as ningen, “person between.” 人間.

We are embedded and entangled with one another. This is the wild world of human relations, community and culture. Because we can long for certain people just as we can long for distant places. It turns out that Melville was deeply in awe of a certain man in real life, much as Ishmael was drawn to Queequeg. This was the great novelist Nathanial Hawthorne, who would “drop germinous seeds” in Melville’s soul.

To Hawthorne, Melville wrote:

Your heart beat in my ribs and mine in yours, and both in God’s… It is a strange feeling — no hopefulness is in it, no despair. Content — that is it; and irresponsibility; but without licentious inclination. I speak now of my profoundest sense of being, not of an incidental feeling.

Whence come you, Hawthorne? By what right do you drink from my flagon of life? And when I put it to my lips — lo, they are yours and not mine. I feel that the Godhead is broken up like the bread at the Supper, and that we are the pieces.

Melville is bewitched by this man, said to be more handsome than Lord Byron and a person who added a “W” to the spelling of his last name so as to unlink himself from an ancestor’s association with those Salem witch trials, about which he would so famously write.

Melville immediately made up his mind after first meeting him to buy a home not six miles from where Hawthorne lived.

And there, he pledged, he would build a tower.

Other artists who dwelled in towers include: Montaigne, Yeats, Rilke, Jung, Vita Sackville-West, George Lucas, among others.

3.

3.

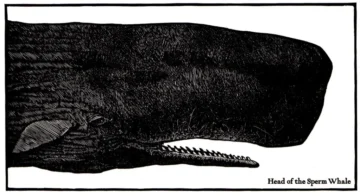

I loved whales long before reading Moby Dick. My first committed social cause was “Save the Whales.” I was a child—maybe ten or eleven years old, when I joined the campaign using my Christmas money to make my first donation. This cause was something I kept up till college. Those were in the days that whales were much on people’s minds. Roger S Payne made his famous discovery about humpback whale song and created a CD of their music in 1970; later persuading National Geographic Magazine to include a disc of their song in an issue that went out to 10.5 million subscribers in 1979. This album not only inspired songs by Pete Seeger, Judy Collins, and Kate Bush, but it also was launched into space aboard Voyager in 1977.

Everyone seemed to be as excited about whales as I was back then. And of all the issues in the world, I would have thought we could have solved that one—since we no longer needed them for oil, right?

How could we not figure out how to let these incredible “charismatic megafauna” survive and flourish?

So, here is a regret I have. And aren’t regrets also the territory of people of a certain age? While I lived in Tokyo, I did something terrible. Trying not to make waves in consensus society Japan, I took a bite of whale at a drinking party when I was working as an Office Lady at Hitachi Logistics in downtown Tokyo. The company HQ was located in the famous Tsukiji Fish market district —and we ate all kinds of fish when we went out. But whale?

Japan is one of the few places in the world that has kept whaling. There is a poem by Misuzu Kaneko (died 1930) that I have long loved called “Whale Memorial” about religious rites once carried out by whaling communities in Japan to honor the dead souls of whales:

Whale memorials are held in spring

around the time flying fish are caught in the sea

bells toll from the temple on the beach

the sound rippling across the water’s surface

as fishermen dressed in haori coats hurry to the temple

in the bay an orphaned whale calf cries listening to the tolling bell

And I wonder how far the sound of the bell will travel

across the sea?

In her book (highly recommended!) Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait, Bathsheba Demuth describes similar traditions in the indigenous communities in Alaska, where the spirit of the dead whale is honored.

In her book (highly recommended!) Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait, Bathsheba Demuth describes similar traditions in the indigenous communities in Alaska, where the spirit of the dead whale is honored.

Isn’t there a difference between sustainable hunting for sustenance versus industrialized all-out war where the animals are seen as objects for profit? Is it meaningful to distinguish between traditional methods of hunting versus the industrialized food of today? Sustenance versus profit. Sustainable versus greed. This is partly why, despite the ban on whaling, the US and Russia permit their indigenous communities to continue traditional hunting practices with limits on the number of slaughtered whales.

To be alive means taking up our place in a chain of conversions,” Demuth writes in her book Floating Coast. “In order to live, something, some being, is always dying.” After centuries of humans’ industrial energy consumption, what will be next to go? This summer, Alaska had its hottest days ever recorded. Seas rising, habitats disappearing, extreme weather events on the rise.

As people act, the climate reacts. Only by understanding that link might we survive, she warns.

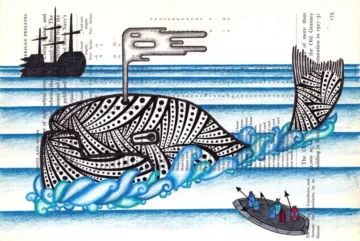

The energy stored in whales once illuminated American homes, cities, and factories. In lanterns, lampposts and lighthouses. Bowheads and sperm whales were intensely hunted by Americans —and this is what Ishmael was doing on that infamous whaler. For the whalers were not eating for sustenance but turning them into profit. This was the big oil of the time.

Toward the end of Floating Coast, Demuth mentions that even after the transition from whale oil to petroleum, whale oil was still used sparingly in the 1970s on nuclear submarines and in ballistic missiles—impervious to cold temperatures, it was the perfect way to keep things working. Philip Hoare in his wonderful book on whales told the story of its use, not just in the nuclear industry under water but on the Hubble telescope.

4.

Whales in space? Really?

It’s no coincidence that the SETI Institute, the NASA program set up to look for other life forms in the universe, would decide to set up a whale language translation study, called CETI. The reasoning is that if we can’t communicate with other species on our own planet, how are we supposed to communicate with aliens?

Of course, we have been able to teach primates, Corvids, parrots and other birds, and certainly dolphins a bit of our human language — But how many words do we speak of Dolphinese or Chimpanzine? And what songs can we sing in Whale-song? In much the way we have to approach SETI communication in terms with communicating with creatures who might not have eyes, ears and a mouth or who think in math, so too must we approach animal communication in terms of their bodies. To speak in the music of whales and the chorus of insects? Or the fragrant language of deer?

Loosely based on a true story, Moby Dick ends in annihilation. Not of the whale, of course, but of the ship—and all on board, save one survivor. In the real-life story Melville was inspired by, a sperm whale attacks and sinks a whaler in the South Pacific. Afraid of cannibals, the surviving crew steers their lifeboats away from the nearby islands. Instead, they row thousands of miles toward the Pacific toward south America. And in a supremely ironic act, the men on the lifeboats, starving and dangerously dehydrated, resort to cannibalism of their own.

That was in the heyday of American whaling when several species of whales were hunted close to extinction.

5.

“Keep True to the Dreams of Thy Youth”, attributed to the German poet Friedrich Schiller, this was a motto that Melville affixed to his writing desk. But how to stay true to our dreams when life somehow always gets in the way!

Rereading Moby-Dick in what was a year of fires and floods and melting ice, I became again the young woman who experienced the novel as a profound invitation to adventure and risk. But I am also the older woman standing in her tower surveying the troubled world she inhabits, now finding in this story a map of a life that she had wanted but might have misplaced. Perhaps it is time to climb down from my tower. And boarding the next ship, chancing fear and storm and shipwreck, in search of whale-song, and that temple bell, where maybe even within the leviathan’s gaping mouth, the great flood-gates of the wonder-world will once again fling open.

Illustrations: From Matt Kish’s Moby Dick in Pictures (one Drawing for Every Page)

A picture of a whale shrine

And the cover of my beautiful Albion edition of the novel

To read:

I think Moby Dick is on many people’s minds these past few years, since Covid.

Dayswork, by Chris Bachelder, Jennifer Habel, was one of the most original novels I’ve read in years. You wouldn’t even know it was a novel since it reads more like a journal, drawing on research notes interspersed with fragments of thoughts about the protagonist’s husband and about their life during the lockdown. A lot is going on balancing work and two kids but the couple more and more talk about Herman Melville and Moby Dick.

Charles Olson’s Call Me Ishmaelle.

And Xiaolu Guo’s feminist re-telling of the novel, Call Me Ishmaelle. Out in the UK last year and coming out in the US in early Jan.

Another whale novel for you: Whalefall, by Daniel Kraus and North Sun, or, the Voyage of the Whaleship Esther, by Ethan Rutherford (National Book Award finalist and an Obama 2025 Best Book)

“Ira and the Whale” Rachel B. Glaser in Lithub

Another favorite whale book I read this year was How to Speak Whale: The Power and Wonder of Listening to Animals. The book started life when its author, naturalist filmmaker Tom Mustill was kayaking in Monterey Bay when a massive humpback breeched on his kayak, “releasing the energy equivalent of forty grenades.” Someone caught it on video, which went viral online, setting Mustill off on a quest to try and understand these wondrous creatures.

Also recommended: The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Sea, by Philip Hoare and A natural history of Moby-Dick: Ahab’s Rolling Sea, by Richard J. King

Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait, by Bathsheba Demuth

More about Kaneko’s whale poem (with a different translation of her poem) by Shaun O’Dwyer in the Japan Times

Beyond Contact: A Guide to SETI and Communicating with Alien Civilizations, Brian McConnell.