by Thomas Fernandes

Like the Thomson’s gazelle of Part I, the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) evolved an ability to communicate with predators. Not by stotting but by flagging the white underside of their tail.

Why is this considered communication? Communication requires intention, distinguishing a cue from a signal. To a deer, a predator’s smell coming from upwind is a cue. By marking their territory, deer leave signals to others. Cues emerge from simple correlation, association of one signal (odor) with another (the presence of a predator). Over evolutionary time, cues can become signals. After detecting a predator, a deer might turn to flee. Predators constantly evaluate whether to pursue a chase, paying close attention to cues of early detection and fitness. Once predators use these cues to abort the chase, deer might evolve increasingly conspicuous displays, like flagging a highly contrasted tail, simply to advertise this cue to the predator. At this point, the fleeting readiness cue evolves into a fleeting readiness signal.

To be relevant the signal should not be only about detection but also about the ability to outrun predators. As predicted, faster deer are observed to be more likely to wag their tails and the proportion of time the tail stands erect increases with flight speed (Caro et al., 1995). While it may seem surprising that slower deer would not try to bluff their way out of a hunt, a signal is only as efficient as it is honest. If tail wagging were used every time regardless of flight capabilities, it would make the signal meaningless. After all, signals are built from correlations that are of interest to both the sender and the receiver. Break the correlation, break the signal, and everybody loses.

To better understand this behavior, a comparison with mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) proves insightful. Both are close cousins with similar mating patterns, feeding habits, body size and morphology. Yet mule deer tend to inhabit more open, rugged terrain, whereas whitetails occupy patchier, more vegetated ground. From these settings, subtle differences emerge. Their ears are longer, their eyes set wider to the sides, and their white rump is conspicuous even when still. In whitetails, by contrast, the pale patch remains hidden until the tail is raised. An inversion that turns concealment into communication. These distinctions may seem minor, but let us follow the trail.

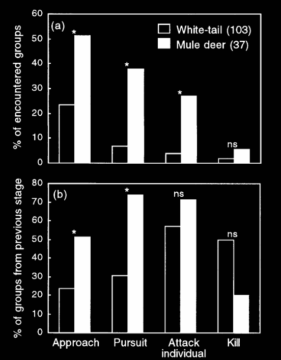

In regions where both species coexist, observations of coyotes hunting reveal a marked divergence. Observers report that coyotes attack mule deer far more often than whitetails: 27% of encounters versus 3.9%. Yet, when attacks occur, the kill rate is 50% for whitetails and 20% for mule deer. These patterns reflect the coyotes’ adaptation to each species’ anti-predation strategies.

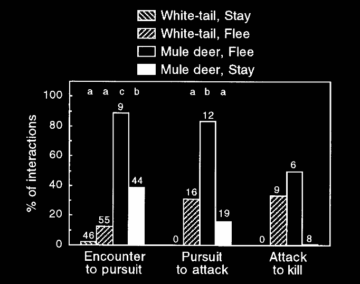

Mule deer detect approaching predators from significantly greater distances, up to eight hundred meters, and always alert upon detection. A critical first move in their defense repertoire. If spotted early enough, they can avoid the encounter altogether. If not, they shift to elevated vantage points, draw together in close groupings, orient toward the threat, and in most cases mount an aggressive defense. Yet the choice between standing ground and running is not made in isolation. It hinges on terrain but also the presence and resolve of nearby deer, whether others will stay and defend, or scatter. When coordination fails, their vulnerability rises sharply as seen in figure 4 for fleeing attempts of mule deer. At each stage coyotes correctly evaluate the prey vulnerability, showing preferential escalation first toward mule deer, then fleeing mule deer. The failure of group coordination increases mortality from approximately 5% of encounters to 15% among isolated individuals that resist, and up to 37% among those that flee. This social uncertainty is what makes early detection necessary to organize. It also makes mule deer behavior harder to predict, rewarding coyotes that press close enough to provoke a reaction. Almost all mule deer are potential targets if they fail to coordinate.

White-tailed deer, by contrast, invariably flee once chased. They can detect predators up to two hundred meters but only alert around fifty meters. Their strategy depends on rapid escape, and such margins are sufficient for them. Signaling clearly pays: whitetails spend less energy evading, and coyotes focus only on high-probability hunts either when very close or when the target is insufficiently fit, such as a fawn.By comparison, mule deer are less predictable and their vulnerability varies accordingly.

Why did these divergent tactics evolve? The proximate answers are ecological. Rugged open country favors a bounding gait and collective defense, while brushy landscapes favor rapid individual flight. Yet there are deeper feedback loops at work. Terrain shapes gait. Gait constrains the possible avoidance strategies. Those strategies in turn shape habitat choice and life history. Over generations, predation pressure and landscape have pushed mule deer and whitetails toward two coherent stable solutions.

Mule deer built for broken ground rely on vigilance and cohesion. Their bounding gait, a stiff, sprung movement lifting several limbs at once, suits steep slopes and rocky terrain where traction is uncertain. This gait makes evasion from coyotes very difficult but allows a defensive strike with forelimbs raised high and hooves poised to repel coyotes. It is an adaptation to the terrain that favors standing ground over outrunning danger. Whitetails, shaped by denser brushy environments, took the opposite path. Their alternating gallop delivers explosive acceleration and a sustained sprint on even ground allowing them to outrun coyotes. Unable to strike, escape is the only reliable option.

That last point is crucial. Fawns are the favorite target of coyotes. As such, the ability to defend one’s children is greatly beneficial. Living in open ground, where detection is more likely, this trait can prove more critical to a species’ success. Indeed, mule deer fawns are less vulnerable than white-tailed fawns in the first few months of life and the following observations from Lingle & Pellis show why:

“In three cases, (mule deer) fawns that were alone with their mothers fled after being repeatedly rushed by coyotes. These mothers then overtook and drove the coyotes back during heated battles lasting about 10 min, while the fawns managed to get several hundred meters in front of the coyotes and near other groups”

The costs and benefits of each strategy ripple across generations. Some, relying on flight as their primary defense, develop sprinting skill rapidly. Others, protected by their peers, can take longer to master more complex defensive maneuvers.

With such effective strategies, one might wonder: how do coyotes manage to survive? Coyotes’ diet consists mostly of smaller prey. Rodents, easily caught but tiny, demand constant foraging: over three thousand a year for sufficient calories (Laundré & Hernández, 2003). Rabbits provide a richer payoff; one can feed a coyote for almost two days. Deer, though far more challenging to catch, offer a month’s worth of food for a single coyote. Chased in packs, the bounty may be shared, yet the effort is worth it. Those are some of the decisions coyotes must weigh; which prey to pursue, when to give up, and how to interpret the signals and cues to their advantage.

At a glance, the two deer are almost indistinguishable. Yet beneath that sameness runs a quiet divergence, two answers to the same challenge. Each has learned to save energy in its own way, to read its landscape and move as the ground allows. What began as a cue becomes a signal, what began as flight becomes strategy. Predation is not just pursuit but exchange: of signs, of attention, of energy. Environment dictates the rules, evolution writes it everywhere for those who care to look.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.