by Mark Harvey

Walking across a piece of my land the other day, I noticed that various grasses had become entirely brown from lack of water. Bromes and Poaceae, normally still green this time of year, looked brittle and were the color of tea. Cheat grass, that invasive species from Eurasia, looked even yellower and drier than it normally does. I picked some of the cheat grass, also known as downy brome, and it practically crumbled in my hands. This has been the driest year I can remember in my part of western Colorado. I don’t just mean statistics based on snowpack and rainfall, because that is only part of the story. Other factors include evaporation rates, timing of the snowmelt and residual lack of moisture in the soil from last year. The first clue that this is an exceptionally dry year came when a spring-fed lake on our ranch never filled with water. Normally by the time the snow melts off, the lake fills to the brim and holds water through the entire summer. This year, even in June it was empty.

Another spring-fed pond that normally stays full all summer is already half empty.

The land has a feeling of wanting to ignite and explode with the slightest spark. It’s the cheat grass that scares me the most for it’s incredibly flammable and covers tens of millions of acres in the intermountain west. Cheat grass has a biological advantage over other native grasses because it germinates earlier than most others, which gives it a head start in the competition for water and soil nutrients. It also dries out sooner than other grasses as the summer wears on and serves as what’s called a “ladder fuel” when it comes to wildfires. The term ladder refers to a ground plant’s ability to help fires climb up onto trees.

According to Glenn Lewis, a fire behavior analyst, the moisture content in western Colorado’s plant communities is at near historic lows—in the 97% percentile since records have been kept.

The great war room for managing wildfires across the nation is up in Boise, Idaho. The National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) is comprised of eight agencies including the Bureau of Land Management, the Forest Service, the National Park Service, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Association of State Foresters, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the US Fire Administration, and the Department of Defense.

Some refer to NIFC as the Pentagon for wildfire management across the nation. The agency is set up to analyze vast swaths of the country that are most likely to catch fire, make predictions about volatility, and in the event of big fires, help dispatch personnel and every kind of resource from radios to helicopters.

NIFC is highly organized, and uses advanced technology to predict and model wildfire behavior. The big factors that suggest an area will catch fire are fuel loads, fuel qualities, and weather. Combine very dry vegetation, high temperatures, vapor pressure deficits, wind, and a stray cigarette or a lightning bolt and you might get a forest fire that burns 50,000 acres and 50 houses.

While the computer modeling for predicting fires is advancing rapidly, based on machine learning, better data, and geospatial technology, it’s still very difficult to forecast just where something will break out. Between the complexities of weather, the vast array of fuels in any given environment, and the mostly random sources of ignition, it’s a hugely complicated business.

During droughts, it’s often obvious what’s going on above ground with dried and brown vegetation, but what happens below the surface can be a mystery. Unconfined aquifers where some farmers and ranchers get their water can rise and fall quickly depending on snowmelt, rainfall and consumption. There was a time when aquifers were poorly understood and unregulated. A little over a hundred years ago in Texas, one W. A East, a citizen of Denison, noticed a well he had been using for years had gone dry shortly after the neighboring railroad company drilled a massive well themselves and began pumping thousands of gallons of water per day for their steam locomotives.

In 1904, East sued the railroad company for drying up his wells, but the Texas courts sided with the railroad, saying in their decision that the source and movement of underground water “are so secret, occult and concealed that an attempt to administer any set of legal rules in respect to them would be involved in hopeless uncertainty, and would be practically be impossible.”

Thus began the long and painful history of the “rule of capture” in Texas which is basically, he who has the biggest pump wins. While Texas has adopted some regulations to manage its aquifers, the rule of capture still holds today in the Lone Star State.

Nowadays hydrologists have a much better picture of how ground water and aquifers work and states like Colorado have much more sophisticated laws and regulations governing ground water than Texas

One new technology that makes what’s going on underground less “secret, occult, and concealed” comes out of program called Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE). GRACE was jointly developed by NASA and The German Aerospace Center (DLR) in the late 1990s and deployed in 2002. It works like this. Not too far above the Earth, there are two satellites orbiting our planet about 15 times per day, measuring groundwater levels, snowpack and glaciation. One satellite is following the other at a distance of about 135 miles and, using microwave technology, scientists can measure the distance between the satellites to within 1 micron.

The satellites travel at a fairly consistent speed, but due to gravitational differences based on variations in the Earth’s mass, the lead satellite slightly accelerates when it flies over a denser region (such as mountain ranges or regions with excess water mass), and the trailing satellite does so shortly thereafter. This causes the distance between them to increase slightly and then return to “normal”, depending on the gravitational pull below. Though the changes in distance between the two satellites is minuscule (mere microns), scientist can infer a lot about ground water from the relationship between the two satellites.

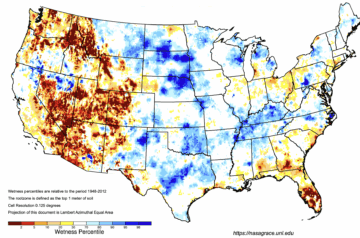

The maps made by NASA of US groundwater, both at the root zone and at the shallow ground water zone (less than 10’ deep) are a mosaic of dark red, light red, yellow, white and blue depending on aridity. Areas with dark red and red are severely dried out (90 to 99 percent of normal based on about 60 years of data). On this year’s July map, huge swaths of the intermountain west and the southwest fall into this category.

Where I live, my observations of our empty and half empty ranch ponds, concur with NASA’s satellite observations—the root-zone soil and the shallow ground water zones are near historic lows when it comes to moisture.

The GRACE program has also shown that massive amounts of ground water have been lost over the last twenty years in the American southwest. In the upper and lower Colorado Basin (combined), data from the satellites shows that approximately 33 cubic kilometers of groundwater storage have been lost. If my math is correct, that’s close to nine trillion gallons, or the equivalent of what 80,000,000 households would use in a year.

The last few weeks the skies in western Colorado have been hazy with smoke from fires both within the state and fires to west. It’s not easy to know whether the air is being fouled by the Turner Gulch Fire in Mesa County near the Utah border or the Dragon Bravo Fire in Arizona—probably both. A small fire broke out near our ranch a couple of weeks ago and was quickly put out by expert teams using a helicopter, a ground crew and engines.

To me, this summer of 2025 has felt like something has truly shifted in Western Colorado. Data has shown incremental annual changes in snowpack, frost-free days, average temperatures, and other vital signs of our state. But maybe those changes have been too gradual to really feel a fundamental change in the state’s character. The ground is moving under our feet. As is the water.