by Dick Edelstein

After creating for a party a playlist of old R&B tracks recently, I was struck by the optimistic mood of so many of the songs that I had selected, by how their hopeful or celebratory moods contrasted with the tone of much of our current popular music, songs that frequently rely on themes expressing cynicism or detachment.

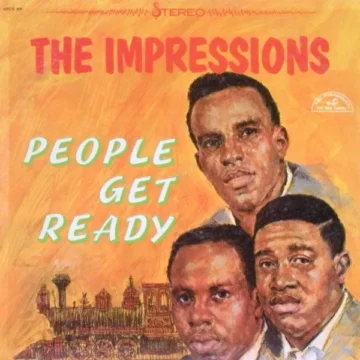

One of my first choices for the playlist was the gospel-inspired song ‘People Get Ready‘ composed by Curtis Mayfield in 1964, not long after the March on Washington and Kennedy’s assassination. The song was first released by The Impressions in 1965 and became one of the first gospel-inspired crossover hits. Before long it had become the unofficial anthem of the Civil Rights Movement, which had already achieved a string of hard fought successes, but not without many tragic events. The track continued to be popular throughout the sixties and seventies, and cover versions were recorded by many well known artists, including Aretha Franklin. Steeped in the tradition of gospel music, Mayfield’s lyrics proclaim the good news and suggest a better future to come:

People get ready

There’s a train a-coming

You don’t need no baggage

You just get on board

All you need is faith

To hear the diesels humming

Don’t need no ticket

You just thank the Lord

Today, we may look back and question the basis of this optimism and whether it was realistic, but I don’t question the religious tone of Curtis Mayfield’s lyrics, since, to me, earnest sincerity has always been the hallmark of his songs. Religious references, in those days, formed an intrinsic part of the ethos of Black music, both gospel and R&B, although in very different ways. While gospel stars like Johnny Taylor and Sam Cooke were able to easily make the transition from gospel to R&B, this move was seen as a betrayal by the true believers of the gospel movement, who considered R&B to be the devil’s music. But the widespread popularity of soul music showed that the devil had many good tunes.

The next choice on my playlist was ‘Shining Star‘ by Earth Wind and Fire, a band that regularly topped the charts throughout the seventies. Along with tracks from Stevie Wonder’s Talking Book and Innervisions albums, EWF tracks were the undisputed top choice at parties of the era. ‘Shining Star’, one of their biggest hits, was a song ahead of its time since the lyrics speak of personal empowerment in a way that is common enough in today’s culture but was much less so in the seventies.

You’re a shining star, no matter who you are

Shining bright to see what you can truly be

‘My Girl‘ by The Temptations was another no-brainer choice for my party list. The song is not only optimistic in tone, its melody is positively buoyant and so is the harmony, not to mention is the lead singing of David Ruffin, so pure that it tugs at your emotions. This is the Motown song par excellence—everything is groovy. It’s Berry Gordy’s ideal—unlimited hit potential and nothing to bother the White folks.

I’ve got sunshine on a cloudy day

When it’s cold outside, I’ve got the month of May

I guess you’d say

What can make me feel this way?

‘Love Train‘ by the O’Jays, like ‘People Get Ready’, makes use of the train image so common in soul and gospel and its lyrics almost sound prophetic today since they refer to Egypt and Israel, as well as to Russia and China.

The next stop that we make will be England

Tell all the folks in Russia, and China, too

Don’t you know that it’s time to get on board?

And let this train keep on riding, riding on through

All of you brothers over in Africa

Tell all the folks in Egypt, and Israel, too

Please don’t miss this train at the station

‘Cause if you miss it, I feel sorry, sorry for you

‘Love Train’ wasn’t just a catchy soul anthem—it was a call for unity and peace during a turbulent time in history that encouraged people from all over the world—England, Russia, China, Egypt, Israel, and Africa—to “join hands” and spread love. It was a musical invitation to transcend borders and differences. The song became an icon of the early disco movement and Philadelphia soul, blending upbeat rhythms with socially conscious lyrics. Its optimistic tone stood out amid the political unrest and war-related anxieties of the early seventies.

Despite having no lyrics at all, ‘Green Onions‘ by Booker T and the MGs somehow manages to be just as optimistic as ‘My Girl’ and ‘Love Train’. A purely instrumental cut, it needs no words to create an optimistic mood. It is driven by an insistent up-tempo rhythm in march time and is cheerfully propelled forward by a lively, repetitive bass line. The brisk march seems to move forward almost without an effort at all, almost conveying a feeling of briskly walking downhill. Its happy message, though largely subliminal, is as clear as the explicit exhortations and declarations in the other songs that are discussed here.

While the original release is iconic, the 2009 remastered version offers a genuine listening treat, so I include a link to it here for anyone who has not yet heard it. In this version, we can not only clearly hear Steve Cropper’s guitar licks, they are given the prominence they deserve, which definitely adds a new quality to the cut.

Booker T. Jones and the Memphis session musicians he habitually worked with were part of a musical revolution that shaped soul, R&B, and rock in the nineteen sixties and later. Their influence is important because of the many hits they contributed to as session musicians and the cultural barriers they broke not only by changing the direction of soul music, but also by including White musicians in the band.

Of course, not all of the R&B songs of the sixties and seventies were optimistic in tone. Two good examples of this trend are Stevie Wonder’s blockbuster hit ‘Living for the City’, cataloguing the ills facing Black Americans , and Johnny “Guitar” Watson’s ‘Ain’t that a Bitch’, a telling indictment of the working conditions of Black Americans and a significant part of the working class in general.

In ‘Living for the City‘ Wonder tells the vivid story of a young Black man born into grinding poverty in Mississippi, whose family labors long hours for meagre wages. The song is a condemnation of poverty and labor exploitation in a segregationist society:

A boy is born in hard time Mississippi

Surrounded by four walls that ain’t so pretty

His parents give him love and affection

To keep him strong, moving in the right direction

Living just enough, just enough for the cityHis father works some days for fourteen hours

And you can bet, he barely makes a dollar

His mother goes to scrub the floors for many

And you’d best believe, she hardly gets a penny

Living just enough, just enough for the city.

Despite Stevie Wonder’s iconic performance on this record, I think his recording was eventually outshone by Ray Charles’ version on his brilliant album True Genius—a seven minute track featuring a preacher-style monologue. This version is much less well known because it never became a radio hit, but I think anyone who is a fan of the song should hear it.

Johnny Guitar Watson’s ‘Ain’t that a Bitch‘ is one of the most eloquent songs describing the social ills and personal difficulties of Black people and other sections of the American working class. The lyrics speak for themselves:

I’m working forty hours

Six long days

And I’m highly embarrassed

Every time I get my pay

And they working everybody

Lord, they working poor folks to death

And when you pay your rent and your car note

You ain’t got a damn thing left

Protest songs evoking the real living and working conditions of the time reflect a current in R&B that began in the sixties and gained traction in the seventies. And they are clearly counterexamples to the trend towards optimism, somewhat contradicting my notion about the optimism of R&B songs during these two decades. However, the political songs were never as common as the more optimistic and cheerful tunes, and one of the reasons for this was the ambivalent attitude of Motown Record’s owner Berry Gordy towards songs about social justice.

Gordy’s stance on political and protest songs reflected his business-oriented approach for the record label. His goal was to create a commercially successful label with a broad appeal and he believed that protest songs could be divisive. He wanted to create music that would be popular with a Black audience but also have the potential to break out of the R&B box and become mainstream popular hits. He was particularly concerned about the commercial implications of releasing overtly political or socially aware music, which he feared would alienate audiences.

However even someone as powerful as Gordy could not manufacture cultural trends, but only amplify the ones he favored. Motown did eventually release some socially conscious songs, such as Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On‘, but the writers and artists involved often had to overcome significant resistance. Gaye had to push back against Gordy’s reluctance and even threaten to stop recording altogether if the track was not released. Eventually, since Berry could not stem the tide of protest that had carried along many of his most iconic song writers, he reluctantly agreed to record some of these tracks, but he still made sure that the overall tone of Motown music did not upset the mainstream listeners.

When I consider the political chaos that seems to assault the world from all sides today, I think of the lives of my parents, which were marked by two world wars and a major economic depression. As a post-war baby boomer of fortunate birth, I feel I have had it easy by comparison. And now when I find it difficult to glimpse the light at the end of tunnel, and when I am unable to find solace in today’s music, I turn to the R&B of my youth to momentarily bathe myself in optimism.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.