Emily Lordi in The New Yorker:

“When the psychohistory of a people is marked by ongoing loss, when entire histories are denied, hidden, erased, documentation can become an obsession,” bell hooks writes in her book “Art on My Mind: Visual Politics,” from 1995. She describes photography, in particular, as an accessible medium through which Black Americans, who had been shut out of white art institutions for most of the twentieth century, could picture themselves as they wished to be seen, and create “private, black-owned and -operated gallery space[s]” within their own homes.

“When the psychohistory of a people is marked by ongoing loss, when entire histories are denied, hidden, erased, documentation can become an obsession,” bell hooks writes in her book “Art on My Mind: Visual Politics,” from 1995. She describes photography, in particular, as an accessible medium through which Black Americans, who had been shut out of white art institutions for most of the twentieth century, could picture themselves as they wished to be seen, and create “private, black-owned and -operated gallery space[s]” within their own homes.

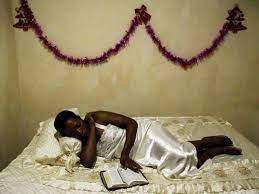

I thought of hooks’s work when viewing “Rest Is Power,” an exhibition at N.Y.U. that gathers more than thirty artists from across the Black diaspora, most of them photographers (standard-bearers like Gordon Parks and Carrie Mae Weems, and younger practitioners like Tyler Mitchell and Daveed Baptiste) to craft a more public, but no less intimate or restorative, counternarrative about Black life. The exhibition, on view at 20 Cooper Square through October 22nd, features Black people in various states of repose (as well as unpopulated interiors and landscapes), from New York to Pujehun, Sierra Leone. The show is part of a broader initiative called the Black Rest Project, through which partner organizations including the Maroon Arts Group, in Columbus, Ohio, and Commissioner, in Miami, will explore the complexities of rest for Black people, and challenge the binary assumption that one can either slow down or make a living, can either struggle or sleep (a myth encoded in the activist mandate to “stay woke”).

More here.