Michael Gibson at City Journal:

In 1963, the philosophers Gilbert Ryle and Isaiah Berlin had lunch with the composer Igor Stravinsky. Ryle, the least famous of the bunch, was the most scathing in his survey of the philosophical landscape. He dubbed the celebrated American pragmatists William James and John Dewey the “Great American Bores.” He condemned the work of French Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin, with its speculation about an emerging world consciousness, as “old teleological pancake.” Then he summed it up in a sweeping crossfire that could serve as the most Oxonian of putdowns: “Every generation or so philosophical progress is set back by the appearance of a ‘genius.’”

What did Ryle have against such geniuses? And is progress in philosophy even possible?

Largely thanks to Ryle and his colleagues, by the 1950s Oxford had ascended to a commanding position in philosophy, at least in the English-speaking world. On the European continent, things were different: German and French philosophers had run headlong down another path. The two broad traditions that emerged from the split after World War I are known as analytic and continental philosophy. The gap between the two styles is vast.

More here.

Over the last year, AI large-language models (LLMs) like

Over the last year, AI large-language models (LLMs) like  One hundred and fifty years ago, John Stuart Mill died in his home in Avignon. His last words were to his step-daughter, Helen Taylor: “You know that I have done my work.”

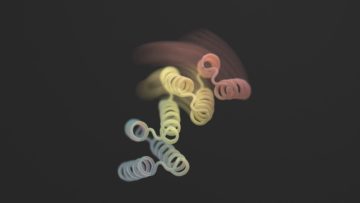

One hundred and fifty years ago, John Stuart Mill died in his home in Avignon. His last words were to his step-daughter, Helen Taylor: “You know that I have done my work.” We often think of proteins as immutable 3D sculptures. That’s not quite right. Many proteins are transformers that twist and change their shapes depending on biological needs. One configuration may propagate damaging signals from a stroke or heart attack. Another may block the resulting molecular cascade and limit harm.

We often think of proteins as immutable 3D sculptures. That’s not quite right. Many proteins are transformers that twist and change their shapes depending on biological needs. One configuration may propagate damaging signals from a stroke or heart attack. Another may block the resulting molecular cascade and limit harm. It’s fitting that choreographer George Balanchine is experiencing a cultural moment around the 40th anniversary of his death. In the ephemeral realm of dance, the longevity of his influence is unique and it shows no signs of waning. Balanchine’s ballets—beloved for their sophisticated abstraction and musicality—have become staples of the repertoire for ballet companies in the United States and beyond, and they have been performed more often since his death than during his lifetime. Two institutions jointly founded by Balanchine and impresario Lincoln Kirstein—the New York City Ballet (NYCB) and the School of American Ballet (SAB)—continue to cultivate his artistic legacy on the stages and in the classrooms of Lincoln Center. Among his other accomplishments, Balanchine made The Nutcracker a Christmas classic in the United States, and for many ballet enthusiasts it would be as difficult to conceive of ballet without Balanchine as it would be to spend the holidays without the Mouse King and the Sugar Plum Fairy.

It’s fitting that choreographer George Balanchine is experiencing a cultural moment around the 40th anniversary of his death. In the ephemeral realm of dance, the longevity of his influence is unique and it shows no signs of waning. Balanchine’s ballets—beloved for their sophisticated abstraction and musicality—have become staples of the repertoire for ballet companies in the United States and beyond, and they have been performed more often since his death than during his lifetime. Two institutions jointly founded by Balanchine and impresario Lincoln Kirstein—the New York City Ballet (NYCB) and the School of American Ballet (SAB)—continue to cultivate his artistic legacy on the stages and in the classrooms of Lincoln Center. Among his other accomplishments, Balanchine made The Nutcracker a Christmas classic in the United States, and for many ballet enthusiasts it would be as difficult to conceive of ballet without Balanchine as it would be to spend the holidays without the Mouse King and the Sugar Plum Fairy. In March, 1929, when the twenty-four-year-old Chinese American actress

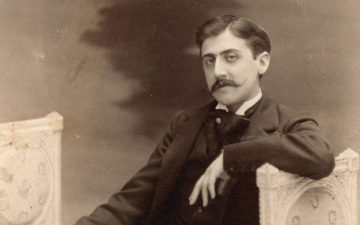

In March, 1929, when the twenty-four-year-old Chinese American actress  Among the many dolls mentioned in Greta Gerwig’s film Barbie there is one associated with time and memory and literally named after Marcel Proust. It didn’t sell well. Perhaps Mattel got the wrong writer. They could have gone for the same Marcel, but as a comedian, a French, philosophical, disguised partner of Dickens. Critics have been finding Proust funny since 1928—he died in 1922. Christopher Prendergast’s

Among the many dolls mentioned in Greta Gerwig’s film Barbie there is one associated with time and memory and literally named after Marcel Proust. It didn’t sell well. Perhaps Mattel got the wrong writer. They could have gone for the same Marcel, but as a comedian, a French, philosophical, disguised partner of Dickens. Critics have been finding Proust funny since 1928—he died in 1922. Christopher Prendergast’s  Science fiction has long entertained the idea of artificial intelligence becoming conscious — think of HAL 9000, the supercomputer-turned-villain in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. With the rapid progress of artificial intelligence (AI), that possibility is becoming less and less fantastical, and has even been acknowledged by leaders in AI. Last year, for instance, Ilya Sutskever, chief scientist at OpenAI, the company behind the chatbot ChatGPT, tweeted that some of the most cutting-edge AI networks

Science fiction has long entertained the idea of artificial intelligence becoming conscious — think of HAL 9000, the supercomputer-turned-villain in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. With the rapid progress of artificial intelligence (AI), that possibility is becoming less and less fantastical, and has even been acknowledged by leaders in AI. Last year, for instance, Ilya Sutskever, chief scientist at OpenAI, the company behind the chatbot ChatGPT, tweeted that some of the most cutting-edge AI networks  About 10 years ago, a very thick book written by a French economist became a surprising bestseller. It was called

About 10 years ago, a very thick book written by a French economist became a surprising bestseller. It was called  As Borat, the first fake news journalist, I interviewed some college students—three young white men in their ballcaps and polo shirts. It only took a few drinks, and soon they were telling me what they really believed. They asked if, in my country, women are slaves. They talked about how, here in the U.S., “the Jews” have “the upper hand.” When I asked, do you have slaves in America?, they replied, “we wish!” “We should have slaves,” one said, “it would be a better country.” Those young men made a choice. They chose to believe some of the oldest and most vile lies that are at the root of all hate. And so it pains me that we have to say it yet again. The idea that people of color are inferior is a lie. The idea that Jews are dangerous and all-powerful is a lie. The idea that women are not equal to men is a lie. The idea that queer people are a threat to our children is a lie.

As Borat, the first fake news journalist, I interviewed some college students—three young white men in their ballcaps and polo shirts. It only took a few drinks, and soon they were telling me what they really believed. They asked if, in my country, women are slaves. They talked about how, here in the U.S., “the Jews” have “the upper hand.” When I asked, do you have slaves in America?, they replied, “we wish!” “We should have slaves,” one said, “it would be a better country.” Those young men made a choice. They chose to believe some of the oldest and most vile lies that are at the root of all hate. And so it pains me that we have to say it yet again. The idea that people of color are inferior is a lie. The idea that Jews are dangerous and all-powerful is a lie. The idea that women are not equal to men is a lie. The idea that queer people are a threat to our children is a lie. Ten years ago, a tech-savvy group of people with type 1

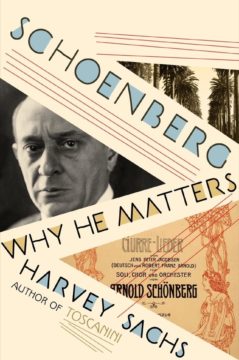

Ten years ago, a tech-savvy group of people with type 1  ARNOLD SCHOENBERG (1874–1951) was a pivotal figure in the development of 20th-century music. Of the thousands of composers who came before and after him, he stood alone both as the embodiment of the high Romanticism of the 19th and early 20th centuries led by Gustav Mahler, Richard Wagner, and Richard Strauss, and as a rebel who broke down the gates of traditions that had ruled music composition for three centuries. After he spent his childhood in pre–World War I Vienna in a Jewish ghetto, Nazi antisemitism drove him from Europe, eventually to land in Los Angeles, where he stayed to the end of his life, teaching first at USC and then UCLA.

ARNOLD SCHOENBERG (1874–1951) was a pivotal figure in the development of 20th-century music. Of the thousands of composers who came before and after him, he stood alone both as the embodiment of the high Romanticism of the 19th and early 20th centuries led by Gustav Mahler, Richard Wagner, and Richard Strauss, and as a rebel who broke down the gates of traditions that had ruled music composition for three centuries. After he spent his childhood in pre–World War I Vienna in a Jewish ghetto, Nazi antisemitism drove him from Europe, eventually to land in Los Angeles, where he stayed to the end of his life, teaching first at USC and then UCLA. The camera zooms in on the person’s arm to reveal the cells, then a cell nucleus. A DNA strand grows on the screen. The camera focuses on a single atom within the strand, dives into a frenetic cloud of rocketing particles, crosses it, and leaves us in oppressive darkness. An initially imperceptible tiny dot grows smoothly, revealing the atomic nucleus. The narrator lectures that the nucleus of an atom is tens of thousands of times smaller than the atom itself, and poetically concludes that we are made from emptiness.

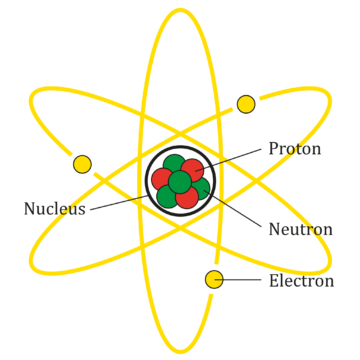

The camera zooms in on the person’s arm to reveal the cells, then a cell nucleus. A DNA strand grows on the screen. The camera focuses on a single atom within the strand, dives into a frenetic cloud of rocketing particles, crosses it, and leaves us in oppressive darkness. An initially imperceptible tiny dot grows smoothly, revealing the atomic nucleus. The narrator lectures that the nucleus of an atom is tens of thousands of times smaller than the atom itself, and poetically concludes that we are made from emptiness.