Rob Madole in The Baffler:

NORMAN MAILER WAS CHARACTERISTICALLY AROUSED the first time he caught a whiff of death drifting from a nearby battlefield. “A curious smell,” he described in a February 1945 letter to his first wife Bea, whom he’d charged with preserving his correspondence as preliminary notes for the big war novel he’d conceived in basic training. “A smell of decay, not exactly sweet as the authors have it, but a good deal like feces leavened with ripe garbage.” Mailer’s tone is that of a gourmand encountering a rare vintage; his olfactory exemplar is Leo Tolstoy, who’d written evocatively in War and Peace about the “stench of rotting flesh” in military hospitals after the Battle of Friedland, the mere memory of which gives Nikolai Rostov, even weeks after the event, sensory hallucinations.

NORMAN MAILER WAS CHARACTERISTICALLY AROUSED the first time he caught a whiff of death drifting from a nearby battlefield. “A curious smell,” he described in a February 1945 letter to his first wife Bea, whom he’d charged with preserving his correspondence as preliminary notes for the big war novel he’d conceived in basic training. “A smell of decay, not exactly sweet as the authors have it, but a good deal like feces leavened with ripe garbage.” Mailer’s tone is that of a gourmand encountering a rare vintage; his olfactory exemplar is Leo Tolstoy, who’d written evocatively in War and Peace about the “stench of rotting flesh” in military hospitals after the Battle of Friedland, the mere memory of which gives Nikolai Rostov, even weeks after the event, sensory hallucinations.

Mailer, however, didn’t share Rostov’s battlefield revulsion, even after the Jeep giving him a tour swerved down a dirt road and arrived at a field of putrefying Japanese corpses, “perhaps twenty or thirty . . . swollen to the dimensions of very obese men.”

More here.

Question: Can an artificial intelligence chatbot assistant, provide responses to patient questions that are of comparable quality and empathy to those written by physicians?

Question: Can an artificial intelligence chatbot assistant, provide responses to patient questions that are of comparable quality and empathy to those written by physicians? In the fictional world of the Broadway musical Avenue Q, Kate Monster is a puppet with a sweet demeanor, a lavender-colored turtleneck, and a bob hairstyle. She works as an assistant kindergarten teacher, and when she finally gets to teach a kindergarten lesson all by herself, she chooses to teach children about the wonders of the World Wide Web. But when she describes her lesson to a reclusive, shaggy-haired neighbor named Trekkie Monster, he interrupts every line with what he says is the real reason for the Internet: porn.

In the fictional world of the Broadway musical Avenue Q, Kate Monster is a puppet with a sweet demeanor, a lavender-colored turtleneck, and a bob hairstyle. She works as an assistant kindergarten teacher, and when she finally gets to teach a kindergarten lesson all by herself, she chooses to teach children about the wonders of the World Wide Web. But when she describes her lesson to a reclusive, shaggy-haired neighbor named Trekkie Monster, he interrupts every line with what he says is the real reason for the Internet: porn. Kant’s account of the self is no doubt the most fascinating but also the most difficult facet of his philosophical thinking. It is complex, multi-layered, and inextricably bound with many central tenets of his system. It is no surprise, then, that interpreters rarely attempt to reconstruct the whole picture but more often focus on a single aspect of it. What is lacking in localized approaches, however, is the sense of how different pieces of the puzzle fit together. Katharina Kraus’s ambitious new book remedies this by offering a much-needed comprehensive treatment of Kant’s view on the self that straddles the a priori-empirical as well as the theoretical-practical divide. The book skillfully maps out crucial interpretive issues that frame different parts of Kant’s picture and the various stances one could take toward them, while introducing fresh alternatives to the discussion. Its thorough engagement with both Kant’s writings and existing scholarship is exemplary. This book deserves to become a standard reference point for any discussion of Kant’s view on the self.

Kant’s account of the self is no doubt the most fascinating but also the most difficult facet of his philosophical thinking. It is complex, multi-layered, and inextricably bound with many central tenets of his system. It is no surprise, then, that interpreters rarely attempt to reconstruct the whole picture but more often focus on a single aspect of it. What is lacking in localized approaches, however, is the sense of how different pieces of the puzzle fit together. Katharina Kraus’s ambitious new book remedies this by offering a much-needed comprehensive treatment of Kant’s view on the self that straddles the a priori-empirical as well as the theoretical-practical divide. The book skillfully maps out crucial interpretive issues that frame different parts of Kant’s picture and the various stances one could take toward them, while introducing fresh alternatives to the discussion. Its thorough engagement with both Kant’s writings and existing scholarship is exemplary. This book deserves to become a standard reference point for any discussion of Kant’s view on the self. The first and only time I went to the Walmart in Iowa City was surreal. When I was in high school, my parents’ business-oriented small press had published a book called The Case Against Walmart that called for a national consumer boycott of the company; the author denounced everything from the superstore’s destruction of environmentally protected lands to its sweatshop labor to its knockoff merchandise. So by the time I made a pilgrimage out to the superstore at age twenty-one, I hadn’t stepped in a Walmart for nearly a decade, and it had acquired this transgressive power—the very act of crossing the threshold was as shameful as it was thrilling. Immediately, I sensed the store’s anonymizing power: outside, I was nearby the Iowa Municipal Airport, en route to the Hy-Vee grocery store; inside, I was anywhere. I didn’t know what I expected, but it was wonderful, and terrible, and weird, and empty, but also full of stuff. In the real world, I was allergic to animals, but I found myself hypnotized in the pet aisle: snake food, dry cat food, wet cat food, Iams, I am what I am. Each shade of paint chip in the Benjamin Moore display bouquet was more erotic than the one before. Primrose Petals, I Love You Pink, Pretty Pink, Hot Lips. Everything was too bright, oversaturated, illuminated in fluorescent Super Soaker–level high beams. I wasn’t high; I didn’t need to be. I barely saw another human, but the accumulation of things constituted many lifetimes of living. I was in a mass graveyard—a place defined by, as Annie Ernaux puts it, “the dead silence of goods as far as the eye could see.”

The first and only time I went to the Walmart in Iowa City was surreal. When I was in high school, my parents’ business-oriented small press had published a book called The Case Against Walmart that called for a national consumer boycott of the company; the author denounced everything from the superstore’s destruction of environmentally protected lands to its sweatshop labor to its knockoff merchandise. So by the time I made a pilgrimage out to the superstore at age twenty-one, I hadn’t stepped in a Walmart for nearly a decade, and it had acquired this transgressive power—the very act of crossing the threshold was as shameful as it was thrilling. Immediately, I sensed the store’s anonymizing power: outside, I was nearby the Iowa Municipal Airport, en route to the Hy-Vee grocery store; inside, I was anywhere. I didn’t know what I expected, but it was wonderful, and terrible, and weird, and empty, but also full of stuff. In the real world, I was allergic to animals, but I found myself hypnotized in the pet aisle: snake food, dry cat food, wet cat food, Iams, I am what I am. Each shade of paint chip in the Benjamin Moore display bouquet was more erotic than the one before. Primrose Petals, I Love You Pink, Pretty Pink, Hot Lips. Everything was too bright, oversaturated, illuminated in fluorescent Super Soaker–level high beams. I wasn’t high; I didn’t need to be. I barely saw another human, but the accumulation of things constituted many lifetimes of living. I was in a mass graveyard—a place defined by, as Annie Ernaux puts it, “the dead silence of goods as far as the eye could see.” F

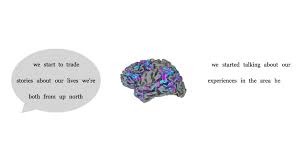

F The study centered on three participants, who came to Dr. Huth’s lab for 16 hours over several days to listen to “The Moth” and other narrative podcasts. As they listened, an fMRI scanner recorded the blood oxygenation levels in parts of their brains. The researchers then used a large language model to match patterns in the brain activity to the words and phrases that the participants had heard.

The study centered on three participants, who came to Dr. Huth’s lab for 16 hours over several days to listen to “The Moth” and other narrative podcasts. As they listened, an fMRI scanner recorded the blood oxygenation levels in parts of their brains. The researchers then used a large language model to match patterns in the brain activity to the words and phrases that the participants had heard. In August

In August Geoffrey Hinton was an artificial intelligence pioneer. In 2012, Dr. Hinton and two of his graduate students at the University of Toronto

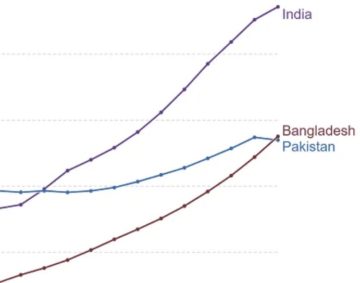

Geoffrey Hinton was an artificial intelligence pioneer. In 2012, Dr. Hinton and two of his graduate students at the University of Toronto  This past week was a happy one for many Indians, who celebrated the milestone of becoming the world’s

This past week was a happy one for many Indians, who celebrated the milestone of becoming the world’s  Have you been feeling anxious about technology lately? If so, you’re in good company. The United Nations has

Have you been feeling anxious about technology lately? If so, you’re in good company. The United Nations has  When OpenAI released its artificial-intelligence chatbot, ChatGPT, to the public at the end of last year, it unleashed a wave of excitement, fear, curiosity and debate that has only grown as rival competitors have accelerated their efforts and members of the public have tested out new A.I.-powered technology. Gary Marcus, an emeritus professor of psychology and neural science at New York University and an A.I. entrepreneur himself, has been one of the most prominent — and critical — voices in these discussions. More specifically, Marcus, a prolific author and writer of the Substack “The Road to A.I. We Can Trust,” as well as the host of a new podcast, “Humans vs. Machines,” has positioned himself as a gadfly to A.I. boosters. At a recent TED conference, he even called for the establishment of an international institution to help govern A.I.’s development and use. “I’m not one of these long-term riskers who think the entire planet is going to be taken over by robots,” says Marcus, who is 53. “But I am worried about what bad actors can do with these things, because there is no control over them. We’re not really grappling with what that means or what the scale could be.”

When OpenAI released its artificial-intelligence chatbot, ChatGPT, to the public at the end of last year, it unleashed a wave of excitement, fear, curiosity and debate that has only grown as rival competitors have accelerated their efforts and members of the public have tested out new A.I.-powered technology. Gary Marcus, an emeritus professor of psychology and neural science at New York University and an A.I. entrepreneur himself, has been one of the most prominent — and critical — voices in these discussions. More specifically, Marcus, a prolific author and writer of the Substack “The Road to A.I. We Can Trust,” as well as the host of a new podcast, “Humans vs. Machines,” has positioned himself as a gadfly to A.I. boosters. At a recent TED conference, he even called for the establishment of an international institution to help govern A.I.’s development and use. “I’m not one of these long-term riskers who think the entire planet is going to be taken over by robots,” says Marcus, who is 53. “But I am worried about what bad actors can do with these things, because there is no control over them. We’re not really grappling with what that means or what the scale could be.” Human technologies are therefore not much different from other innovations produced in our planet’s 3.8-billion-year living history — with the exception that they are in our evolutionary future, not our past. Multicellular organisms evolved vision; what I will call “multisocietial aggregates” of humans evolved microscopes and telescopes, which are capable of seeing into the smallest and largest scales of our universe. Life seeing life. All of these innovations are based on trial and error and selection and evolution on past objects.

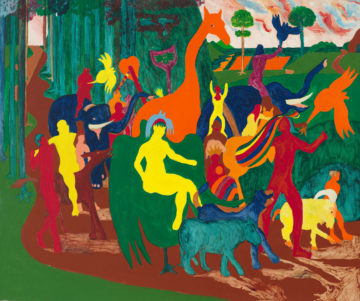

Human technologies are therefore not much different from other innovations produced in our planet’s 3.8-billion-year living history — with the exception that they are in our evolutionary future, not our past. Multicellular organisms evolved vision; what I will call “multisocietial aggregates” of humans evolved microscopes and telescopes, which are capable of seeing into the smallest and largest scales of our universe. Life seeing life. All of these innovations are based on trial and error and selection and evolution on past objects. There is no exact word for what Thompson does with the Old Masters. His paintings—the subject of “Bob Thompson: Agony & Ecstasy,” the unmissable show at Rosenfeld, and another, “Bob Thompson: So Let Us All Be Citizens,” at 52 Walker—contain hundreds of motifs snatched from the Western canon, wedged into dense compositions, and coated in bright colors. The results are too calm for parody and too self-secure for homage. Stanley Crouch thought that Thompson, a jazz fanatic, improvised on European art the way a saxophonist improvises on standards, but even that seems a notch too reverent. He doesn’t riff on masterpieces so much as rifle through them, grabbing a handful of Goya or Tintoretto as though reaching for the cadmium yellow. For “The Entombment” (1960), his painting of a hatted man tumbling off his horse, he seems to have taken the lifeless, drooping torso from El Greco’s “The Entombment of Christ” (which El Greco lifted from Michelangelo, but that’s another story) and cast it in a drama of his own making, so that every brushstroke whooshes toward the bottom like a waterfall.

There is no exact word for what Thompson does with the Old Masters. His paintings—the subject of “Bob Thompson: Agony & Ecstasy,” the unmissable show at Rosenfeld, and another, “Bob Thompson: So Let Us All Be Citizens,” at 52 Walker—contain hundreds of motifs snatched from the Western canon, wedged into dense compositions, and coated in bright colors. The results are too calm for parody and too self-secure for homage. Stanley Crouch thought that Thompson, a jazz fanatic, improvised on European art the way a saxophonist improvises on standards, but even that seems a notch too reverent. He doesn’t riff on masterpieces so much as rifle through them, grabbing a handful of Goya or Tintoretto as though reaching for the cadmium yellow. For “The Entombment” (1960), his painting of a hatted man tumbling off his horse, he seems to have taken the lifeless, drooping torso from El Greco’s “The Entombment of Christ” (which El Greco lifted from Michelangelo, but that’s another story) and cast it in a drama of his own making, so that every brushstroke whooshes toward the bottom like a waterfall.