Benj Edwards in Ars Technica:

During his response, Snoop described how conversing with a large language model (such as ChatGPT or Bing Chat) reminds him of sci-fi movies he watched as a kid. Showing that he keeps up with current events, Snoop also referenced Geoffery Hinton, who resigned this week from Google so he could speak of the dangers of AI without conflicts of interest:

During his response, Snoop described how conversing with a large language model (such as ChatGPT or Bing Chat) reminds him of sci-fi movies he watched as a kid. Showing that he keeps up with current events, Snoop also referenced Geoffery Hinton, who resigned this week from Google so he could speak of the dangers of AI without conflicts of interest:

Well I got a motherf*cking AI right now that they did made for me. This n***** could talk to me. I’m like, man this thing can hold a real conversation? Like real for real? Like it’s blowing my mind because I watched movies on this as a kid years ago. When I see this sh*t I’m like what is going on? And I heard the dude, the old dude that created AI saying, “This is not safe, ’cause the AIs got their own minds, and these motherf*ckers gonna start doing their own sh*t. I’m like, are we in a f*cking movie right now, or what? The f*ck man? So do I need to invest in AI so I can have one with me? Or like, do y’all know? Sh*t, what the f*ck?” I’m lost, I don’t know.

More here.

The phrase « it’s not too late », for me, brings an artificial smile. I stumble onto it as I walk into a bookstore and see the flashy Carbon Almanac (2022) promoted at the entrance, one of many such books to appear in the last, late year. It shouts from the cover: « It’s not too late. » The foreword was written by Seth Godin, a marketing guru out of the dot-com avantgarde. What will save us is « the hope that comes from realizing that it’s not too late. » The refrain is a staple of the genre. Another entry, a new report from the Club of Rome entitled Earth for All: A Survival Guide for Humanity, offers a kindred burst of optimism about the future against the backdrop of a bleak present. Greater planetary health and social well-being are within reach. The authors will « show you that this is indeed fully possible ». Meanwhile the heavy-weight United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released two punchy reports of its own in 2022. They hammered the message that countries’ pledges to cut emissions fall far below climate change targets, and that the impact of climate change is already devastating for many parts of humanity, the ecosystem, and for the biodiversity that now suffers a mass extinction.

The phrase « it’s not too late », for me, brings an artificial smile. I stumble onto it as I walk into a bookstore and see the flashy Carbon Almanac (2022) promoted at the entrance, one of many such books to appear in the last, late year. It shouts from the cover: « It’s not too late. » The foreword was written by Seth Godin, a marketing guru out of the dot-com avantgarde. What will save us is « the hope that comes from realizing that it’s not too late. » The refrain is a staple of the genre. Another entry, a new report from the Club of Rome entitled Earth for All: A Survival Guide for Humanity, offers a kindred burst of optimism about the future against the backdrop of a bleak present. Greater planetary health and social well-being are within reach. The authors will « show you that this is indeed fully possible ». Meanwhile the heavy-weight United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released two punchy reports of its own in 2022. They hammered the message that countries’ pledges to cut emissions fall far below climate change targets, and that the impact of climate change is already devastating for many parts of humanity, the ecosystem, and for the biodiversity that now suffers a mass extinction. The International Monetary Fund approved a

The International Monetary Fund approved a  A little history never hurt anybody. We can start the clock in 1920. In February of that year, the journal Nature reported the

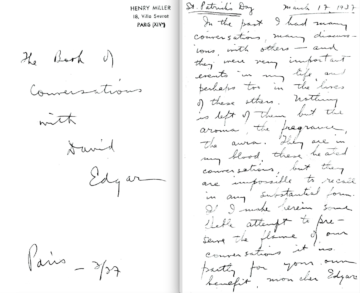

A little history never hurt anybody. We can start the clock in 1920. In February of that year, the journal Nature reported the  So many times, in listening to you, I have had the feeling that the word neurosis is a very inadequate one to describe the struggle which you are waging with yourself. “With yourself”—there perhaps is the only link with the process which has been conveniently dubbed a malady. This same malady, looked at in another way, might also be considered a preparatory stage to a “higher” way of life. That is, as the very chemistry of the evolutionary process. In the course of this most interesting disease the conflict of “opposites” is played out to the last ditch. Everything presents itself to the mind in the form of dichotomy. This is not at all strange when one reflects that the awareness of “opposites” is but a means of bringing to consciousness the need for tension, polarity. “God

So many times, in listening to you, I have had the feeling that the word neurosis is a very inadequate one to describe the struggle which you are waging with yourself. “With yourself”—there perhaps is the only link with the process which has been conveniently dubbed a malady. This same malady, looked at in another way, might also be considered a preparatory stage to a “higher” way of life. That is, as the very chemistry of the evolutionary process. In the course of this most interesting disease the conflict of “opposites” is played out to the last ditch. Everything presents itself to the mind in the form of dichotomy. This is not at all strange when one reflects that the awareness of “opposites” is but a means of bringing to consciousness the need for tension, polarity. “God  When we talk about artificial intelligence, we rely on metaphor, as we always do when dealing with something new and unfamiliar. Metaphors are, by their nature, imperfect, but we still need to choose them carefully, because bad ones can lead us astray. For example, it’s become very common to compare powerful A.I.s to genies in fairy tales. The metaphor is meant to highlight the difficulty of making powerful entities obey your commands; the computer scientist Stuart Russell has cited the parable of King Midas, who demanded that everything he touched turn into gold, to illustrate the dangers of an A.I. doing what you tell it to do instead of what you want it to do. There are multiple problems with this metaphor, but one of them is that it derives the wrong lessons from the tale to which it refers. The point of the Midas parable is that greed will destroy you, and that the pursuit of wealth will cost you everything that is truly important. If your reading of the parable is that, when you are granted a wish by the gods, you should phrase your wish very, very carefully, then you have missed the point.

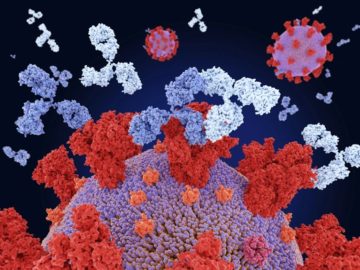

When we talk about artificial intelligence, we rely on metaphor, as we always do when dealing with something new and unfamiliar. Metaphors are, by their nature, imperfect, but we still need to choose them carefully, because bad ones can lead us astray. For example, it’s become very common to compare powerful A.I.s to genies in fairy tales. The metaphor is meant to highlight the difficulty of making powerful entities obey your commands; the computer scientist Stuart Russell has cited the parable of King Midas, who demanded that everything he touched turn into gold, to illustrate the dangers of an A.I. doing what you tell it to do instead of what you want it to do. There are multiple problems with this metaphor, but one of them is that it derives the wrong lessons from the tale to which it refers. The point of the Midas parable is that greed will destroy you, and that the pursuit of wealth will cost you everything that is truly important. If your reading of the parable is that, when you are granted a wish by the gods, you should phrase your wish very, very carefully, then you have missed the point. Antibodies are among the immune system’s key weapons against infection. The proteins have become a darling of the biotechnology industry, in part because they can be engineered to attach to almost any protein imaginable to manipulate its activity. But generating antibodies with useful properties and improving on these involves “a lot of brute-force screening”, says Brian Hie, a computational biologist at Stanford who also co-led the study.

Antibodies are among the immune system’s key weapons against infection. The proteins have become a darling of the biotechnology industry, in part because they can be engineered to attach to almost any protein imaginable to manipulate its activity. But generating antibodies with useful properties and improving on these involves “a lot of brute-force screening”, says Brian Hie, a computational biologist at Stanford who also co-led the study. In a lab mouse version of

In a lab mouse version of  D

D Recently, a friend and I went to a screening of one of our favorite movies, Moonstruck, followed by a conversation with the screenwriter, now in his early seventies. Onstage he was quick-witted and charming, just the kind of person I’d expected to pen such a smart, savory love story. Afterward, as we headed home on the packed subway, I mentioned to my friend that I’d found the screenwriter to be very handsome. She agreed. We wondered aloud if he had grown into his good looks or if he’d always possessed them. Then we took to Google for the answer.

Recently, a friend and I went to a screening of one of our favorite movies, Moonstruck, followed by a conversation with the screenwriter, now in his early seventies. Onstage he was quick-witted and charming, just the kind of person I’d expected to pen such a smart, savory love story. Afterward, as we headed home on the packed subway, I mentioned to my friend that I’d found the screenwriter to be very handsome. She agreed. We wondered aloud if he had grown into his good looks or if he’d always possessed them. Then we took to Google for the answer.

Democrats were once the party of the working class. From the New Deal era through the mid-1960s, clear majorities of

Democrats were once the party of the working class. From the New Deal era through the mid-1960s, clear majorities of  ISTANBUL HAS THE WORLD’S LARGEST AIRPORT,

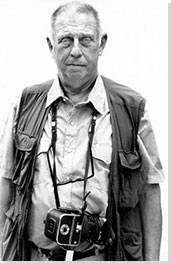

ISTANBUL HAS THE WORLD’S LARGEST AIRPORT, Coen began by leafing through books of Friedlander pictures and decided to arrange the new book to draw attention to Friedlander’s compositional approaches. “Looking through these books and going back and forth, it was a pattern recognition for me — patterns which I know are instinctive but are manifold in everything he does,” he said.

Coen began by leafing through books of Friedlander pictures and decided to arrange the new book to draw attention to Friedlander’s compositional approaches. “Looking through these books and going back and forth, it was a pattern recognition for me — patterns which I know are instinctive but are manifold in everything he does,” he said.