Alex Turnbull in Phenomenal World:

Alex Turnbull in Phenomenal World:

The energy system that underpins contemporary life is marked with blindspots. Take the fossil fuel sector. Facing simultaneous existential and geopolitical vulnerability—due to Russia invading Ukraine, advances in renewable energy, and the climate imperative—there is profound uncertainty about how demand for fossil fuels will transform over the next five to seven years, the time it takes to bring a new gas or offshore oil field online. On the supply side, that uncertainty is matched by the lack of knowledge and monitoring of physical flows of commodities—let alone the kind of detailed information needed to model the ways that geopolitical, climate, and technological disruptions may play out.

Climate campaigners aim for an end to fossil fuel extraction—the minimum requirement to reduce catastrophic and irreversible climatic harm. But with much built infrastructure still relying on fossil fuels, unexpected supply shocks roil households, firms, and governments. New analysis from Isabella Weber, Jesus Lara Jauegui, Lucas Teixeira, and Luiza Nassif Pires shows that energy—in particular petroleum, coal, and oil and gas extraction—are intrinsically more important to inflation than other prices.

What if policymakers could assess inflation with the knowledge that it is driven partly by geopolitical shocks with an unknown timeframe to resolution, and can be approached by policy tools, poured concrete, and steel? These micro considerations do not tend to filter up to the macro modelers whose work informs monetary and fiscal policy. The consequences are significant.

More here.

Marco D’Eramo in Sidecar:

Marco D’Eramo in Sidecar: David Kurnick in Bookforum:

David Kurnick in Bookforum: Paul Grimstad in The Baffler:

Paul Grimstad in The Baffler: On August 11th an unemployed 42-year-old grabbed his shotgun and a large jerry can of petrol. Dressed in a T-shirt and flip-flops, Bassam al-Sheikh Hussein walked into a

On August 11th an unemployed 42-year-old grabbed his shotgun and a large jerry can of petrol. Dressed in a T-shirt and flip-flops, Bassam al-Sheikh Hussein walked into a  Bushra Rehman’s stunningly beautiful coming-of-age novel “Roses, in the Mouth of a Lion” is set in the Corona neighborhood of Queens, New York, which was enshrined in pop culture by Paul Simon’s 1972 hit “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard.” Rehman’s exuberant young protagonist, Razia, knows the song well, although it puzzles her. “Why would Paul Simon be singing about Corona?” she muses. “I didn’t see many white people there unless they were policemen or firemen, and I didn’t think Paul Simon had ever been one of those.”

Bushra Rehman’s stunningly beautiful coming-of-age novel “Roses, in the Mouth of a Lion” is set in the Corona neighborhood of Queens, New York, which was enshrined in pop culture by Paul Simon’s 1972 hit “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard.” Rehman’s exuberant young protagonist, Razia, knows the song well, although it puzzles her. “Why would Paul Simon be singing about Corona?” she muses. “I didn’t see many white people there unless they were policemen or firemen, and I didn’t think Paul Simon had ever been one of those.” I

I Failure, as Costica Bradatan puts it in his bracing new book, is good for you, but not for the reasons you might think. “In Praise of Failure” is maddening, disturbing, exasperating, seductive — I found myself turned around at so many points that even as I was closing in on the last chapter I wasn’t quite sure where I would land at the end.

Failure, as Costica Bradatan puts it in his bracing new book, is good for you, but not for the reasons you might think. “In Praise of Failure” is maddening, disturbing, exasperating, seductive — I found myself turned around at so many points that even as I was closing in on the last chapter I wasn’t quite sure where I would land at the end. You might worry about offending someone, or lack the time to articulate your disagreement. You may even find yourself in a conversational context so polarised that introducing an objection will likely backfire.

You might worry about offending someone, or lack the time to articulate your disagreement. You may even find yourself in a conversational context so polarised that introducing an objection will likely backfire. For years, I resisted

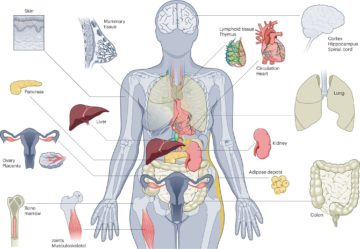

For years, I resisted  Multiple researchers at the Jackson Laboratory (JAX) are taking part in an ambitious research program spanning several top research institutions to study senescent cells. Senescent cells stop dividing in response to stressors and seemingly have a role to play in human health and the aging process. Recent research with mice suggests that clearing senescent cells delays the onset of age-related dysfunction and disease as well as all-cause mortality.

Multiple researchers at the Jackson Laboratory (JAX) are taking part in an ambitious research program spanning several top research institutions to study senescent cells. Senescent cells stop dividing in response to stressors and seemingly have a role to play in human health and the aging process. Recent research with mice suggests that clearing senescent cells delays the onset of age-related dysfunction and disease as well as all-cause mortality. E

E In a quiet group chat in an obscure part of the internet, a small number of anonymous accounts are swapping references from academic publications and feverishly poring over complex graphs of DNA analysis. These are not your average trolls, but scholars, researchers and students who have come together online to discuss the latest findings in archaeology. Why would established academics not be having these conversations in a conference hall or a lecture theatre? The answer might surprise you.

In a quiet group chat in an obscure part of the internet, a small number of anonymous accounts are swapping references from academic publications and feverishly poring over complex graphs of DNA analysis. These are not your average trolls, but scholars, researchers and students who have come together online to discuss the latest findings in archaeology. Why would established academics not be having these conversations in a conference hall or a lecture theatre? The answer might surprise you. I work on AI alignment,

I work on AI alignment,  That we often are not the masters of our own machines, and can even become their witless lackeys, is a cautionary claim as old as the Hebrew prophet Isaiah and as urgent as the latest bogus newsfeed on Dr. Fauci’s evil ways. (Instead of saving lives, he’s been busy, don’t you know, torturing puppies, rendering impotent our patriotic men, and implanting surveillance chips in our brains: accusations all conveyed via apps relentlessly surveilled by Facebook, Apple, Google, and their like.) As a species gifted with inventive minds and opposable thumbs, we are ever about the business of generating new tools and techniques that will, we are certain, better our lives. Time after time, though, those new methods and machines also prove to change our public spaces and private selves in radical ways we fail to foresee and come to regret.

That we often are not the masters of our own machines, and can even become their witless lackeys, is a cautionary claim as old as the Hebrew prophet Isaiah and as urgent as the latest bogus newsfeed on Dr. Fauci’s evil ways. (Instead of saving lives, he’s been busy, don’t you know, torturing puppies, rendering impotent our patriotic men, and implanting surveillance chips in our brains: accusations all conveyed via apps relentlessly surveilled by Facebook, Apple, Google, and their like.) As a species gifted with inventive minds and opposable thumbs, we are ever about the business of generating new tools and techniques that will, we are certain, better our lives. Time after time, though, those new methods and machines also prove to change our public spaces and private selves in radical ways we fail to foresee and come to regret.