Month: December 2022

Mike Hodges (1932 – 2022) Screenwriter And Director

Thom Bell (1943 – 2022) Singer/Songwriter

Fado Music from Portugal – Traditional

‘Sweet Days Of Discipline’ By Fleur Jaeggy

Geneva Abdul at The Guardian:

Fleur Jaeggy would like to see herself as something of a mystic.

Fleur Jaeggy would like to see herself as something of a mystic.

It’s something she aspires to, she admitted in an interview last year. The word mystic derives from the Greek mustē, an “initiated person”. When re-reading Sweet Days of Discipline, arguably the Swiss Italian author’s most famous work, it’s evident that she is such a person. Jaeggy is in on a secret, reaching at something beyond our understanding.

The novel from 1989, both slim and surreal, is centred around friendship at a boarding school. Set in postwar Switzerland, it follows the curious dynamics of the narrator who desires her schoolgirl companion Frédérique.

more here.

‘The Velveteen Rabbit’ At 100

Michael Patrick Hearn at The Washington Post:

The story behind the story of “The Velveteen Rabbit” is itself a kind of fairy tale. Much of it was revealed to me during an interview I did with Margery’s daughter, Pamela Bianco, in 1979. Pamela, born in London in 1906, was an art prodigy, and by the tender age of 12, was one of the most famous children in the world. She was 62 when I met her and working in relative obscurity, as she had done for much of her adult life. During our lengthy conversation, she described the evolution of “The Velveteen Rabbit” and her crucial part in its inception. Pamela was the most childlike person I have ever met. That may well be because her childhood was taken from her. I have never quite forgotten her.

The story behind the story of “The Velveteen Rabbit” is itself a kind of fairy tale. Much of it was revealed to me during an interview I did with Margery’s daughter, Pamela Bianco, in 1979. Pamela, born in London in 1906, was an art prodigy, and by the tender age of 12, was one of the most famous children in the world. She was 62 when I met her and working in relative obscurity, as she had done for much of her adult life. During our lengthy conversation, she described the evolution of “The Velveteen Rabbit” and her crucial part in its inception. Pamela was the most childlike person I have ever met. That may well be because her childhood was taken from her. I have never quite forgotten her.

Pamela began drawing at about age 4 — not the usual formless doodles of little kids but remarkably sophisticated faces and figures. She sketched rabbits and guinea pigs and fairies and angels and little girls.

more here.

Chicago Christmas, 1984: How a holiday party went wrong

George Saunders in The New Yorker:

At twenty-six, at the embarrassing end of a series of attempts at channelling Kerouac, I was beyond broke, back in my home town, living in my aunt and uncle’s basement. Having courted and won a girl I had courted but never come close to winning in high school, I was now losing her via my pathetically dwindling prospects. One night she said, “I’m not saying I’m great or anything, but still I think I deserve better than this.”

At twenty-six, at the embarrassing end of a series of attempts at channelling Kerouac, I was beyond broke, back in my home town, living in my aunt and uncle’s basement. Having courted and won a girl I had courted but never come close to winning in high school, I was now losing her via my pathetically dwindling prospects. One night she said, “I’m not saying I’m great or anything, but still I think I deserve better than this.”

That fall, my uncle called in a favor and soon I was on a roofing crew, one of three grunts riding from job to job in the freezing open back of a truck. My fellow-grunts, Leon and John, were the only black guys on the crew, and hence I was known as the Great White Hope. Once everyone had seen me work, I became the Great White Dope. Our job was to move the hot tar from a vat on the ground to the place on the roof where the real roofing was done. Leon had a thick Mississippi accent and no top teeth. He stayed on the ground, pulleying the smoking buckets up to us, muttering obscenities at passing grannies and schoolgirls. John was forty-two, gentle-voiced, and dignified, with a salt-and-pepper beard and his own roofing tools, which he brought to work every day, even though he was never allowed to do anything but lug tar. John had roofed all his adult life, and claimed to have virtuosoed his way into this job by appearing on the job site one day and outshingling the best white shingler.

More here.

Brain stimulation boosts hearing in rats with ear implants

Miriam Naddaf in Nature:

Stimulating neurons that are linked to alertness helps rats with cochlear implants learn to quickly recognize tunes, researchers have found. The results suggest that activity in a brain region called the locus coeruleus (LC) improves hearing perception in deaf rodents. Researchers say the insights are important for understanding how the brain processes sound, but caution that the approach is a long way from helping people. “It’s like we gave them a cup of coffee,” says Robert Froemke, an otolaryngologist at New York University School of Medicine and a co-author of the study, published in Nature on 21 December1. Cochlear implants use electrodes in the inner-ear region called the cochlea, which is damaged in people who have severe or total hearing loss. The device converts acoustic sounds into electrical signals that stimulate the auditory nerve, and the brain learns to process these signals to make sense of the auditory world.

Stimulating neurons that are linked to alertness helps rats with cochlear implants learn to quickly recognize tunes, researchers have found. The results suggest that activity in a brain region called the locus coeruleus (LC) improves hearing perception in deaf rodents. Researchers say the insights are important for understanding how the brain processes sound, but caution that the approach is a long way from helping people. “It’s like we gave them a cup of coffee,” says Robert Froemke, an otolaryngologist at New York University School of Medicine and a co-author of the study, published in Nature on 21 December1. Cochlear implants use electrodes in the inner-ear region called the cochlea, which is damaged in people who have severe or total hearing loss. The device converts acoustic sounds into electrical signals that stimulate the auditory nerve, and the brain learns to process these signals to make sense of the auditory world.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Postscript

And some time make the time to drive out west

Into County Clare, along the Flaggy Shore,

In September or October, when the wind

And the light are working off each other

So that the ocean on one side is wild

With foam and glitter, and inland among stones

The surface of a slate-grey lake is lit

By the earthed lightning of a flock of swans,

Their feathers roughed and ruffling, white on white,

Their fully grown headstrong-looking heads

Tucked or cresting or busy underwater.

Useless to think you’ll park and capture it

More thoroughly. You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.

By Seamus Heaney

from The Spirit Level

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1996

The Media Very Rarely Lies

Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten:

With a title like that, obviously I will be making a nitpicky technical point. I’ll start by making the point, then explain why I think it matters.

With a title like that, obviously I will be making a nitpicky technical point. I’ll start by making the point, then explain why I think it matters.

The point is: the media rarely lies explicitly and directly. Reporters rarely say specific things they know to be false. When the media misinforms people, it does so by misinterpreting things, excluding context, or signal-boosting some events while ignoring others, not by participating in some bright-line category called “misinformation”.

Let me give a few examples from both the alternative and establishment medias.

More here.

How the CDC Abandoned Science

Vinay Prasad in Tablet:

The main federal agency guiding America’s pandemic policy is the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, which sets widely adopted policies on masking, vaccination, distancing, and other mitigation efforts to slow the spread of COVID and ensure the virus is less morbid when it leads to infection. The CDC is, in part, a scientific agency—they use facts and principles of science to guide policy—but they are also fundamentally a political agency: The director is appointed by the president of the United States, and the CDC’s guidance often balances public health and welfare with other priorities of the executive branch.

The main federal agency guiding America’s pandemic policy is the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, which sets widely adopted policies on masking, vaccination, distancing, and other mitigation efforts to slow the spread of COVID and ensure the virus is less morbid when it leads to infection. The CDC is, in part, a scientific agency—they use facts and principles of science to guide policy—but they are also fundamentally a political agency: The director is appointed by the president of the United States, and the CDC’s guidance often balances public health and welfare with other priorities of the executive branch.

…Ultimately, science is not a political sport. It is a method to ascertain truth in a chaotic, uncertain universe. Science itself is transcendent, and will outlast our current challenges no matter what we choose to believe. But the more it becomes subordinate to politics—the more it becomes a slogan rather than a method of discovery and understanding—the more impoverished we all become. The next decade will be critical as we face an increasingly existential question: Is science autonomous and sacred, or a branch of politics? I hope we choose wisely, but I fear the die is already cast.

More here.

Glass frogs turn translucent by ‘hiding’ blood in their liver

Corryn Wetzel in New Scientist:

Glass frogs can boost their transparency by up to 61 per cent by storing most of their blood in their liver while they sleep. Researchers hope that understanding how the frogs manage to pool their blood this way without experiencing blood clots could provide new insights into preventing dangerous clots in other animals, including humans.

Glass frogs can boost their transparency by up to 61 per cent by storing most of their blood in their liver while they sleep. Researchers hope that understanding how the frogs manage to pool their blood this way without experiencing blood clots could provide new insights into preventing dangerous clots in other animals, including humans.

The tropical, marshmallow-sized amphibians spend their days sleeping on bright green leaves and foraging for food under the cover of dark. Being semi-see-through helps glass frogs avoid being spotted by predators, but it’s a challenging biological task, as most animals need to continuously pump red blood cells throughout their body to deliver oxygen to their tissues.

More here.

What Annie Ernaux Owes To Memory

David McAllister at Prospect Magazine:

A novel, which is fiction, can never be classified as nonfiction—indeed, a “nonfiction novel” sounds like a contradiction in terms. This is because when we use these two categories, we are not talking about form or content—as we might with more granular terms, such as autofiction, memoir or biography—but making a judgement call. We are saying: these are the books that tell “the truth”, whereas these are the ones that do not.

A novel, which is fiction, can never be classified as nonfiction—indeed, a “nonfiction novel” sounds like a contradiction in terms. This is because when we use these two categories, we are not talking about form or content—as we might with more granular terms, such as autofiction, memoir or biography—but making a judgement call. We are saying: these are the books that tell “the truth”, whereas these are the ones that do not.

Annie Ernaux, the latest recipient of the Nobel prize in literature, exposes the linguistic shallowness of these classifications. She is an author of novels that adopt only the most threadbare fictional guises; a deeply personal memoirist who looks back on her life, as she puts it, “like a historian with a character from the past”; and the writer of an experimental autobiography, The Years, that wound up on the shortlist for an international prize in fiction. Any contradiction or category error here is a quirk of translation. In Ernaux’s native France, the concept of la non-fiction is virtually non-existent; she is at greater liberty than we are to dismiss such poor attempts at labelling. “Our experience of the world cannot be subject to classification,” she writes in Exteriors.

more here.

Annie Ernaux, Nobel Prize Lecture

An Interview With Jean-Luc Marion

Kenneth L. Woodward and Jean-Luc Marion at Commonweal:

KW: Many philosophers have said that a certain attitude is required in order to philosophize. For example, the neo-Thomist Josef Pieper said a philosopher had to have a sense of wonder. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel said “radical amazement” is required. You have said the capacity to be astonished is essential. What do you mean by astonishment?

KW: Many philosophers have said that a certain attitude is required in order to philosophize. For example, the neo-Thomist Josef Pieper said a philosopher had to have a sense of wonder. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel said “radical amazement” is required. You have said the capacity to be astonished is essential. What do you mean by astonishment?

JLM: Good question. If I may be a bit polemical, I would say that the greatest possible failure for a professional philosopher is never to be astonished. And many philosophers are in that situation. They philosophize using a set of concepts or tools that protect them against encountering anything new. They have enough ways to make any question lead to a (pre-determined) answer, or even to disappear. But my experience of philosophy—and it’s why people like Descartes or Heidegger were so important—is that philosophy begins when you have this gift of a question that resists an answer. By “answer,” I mean one that is based on what was known before that question was asked. A new question opens up a new landscape that you cannot walk through unless you get a new pair of shoes.

more here.

“The Oxen” by Thomas Hardy, read by Robert Pinsky

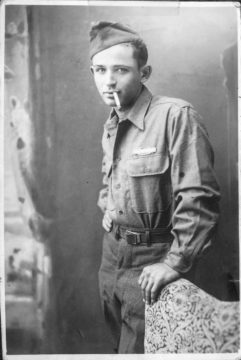

The Making of Norman Mailer: The young man went to war and became a novelist. But did he ever really come back?

David Denby in The New Yorker:

When Norman Mailer was inducted into the Army, in March, 1944, he was a freshly married twenty-one-year-old Harvard graduate, a slight young man of five feet eight inches and a hundred and thirty-five pounds. In the previous few years, he had published some stories and written a play and two novels (one of them published, in a typescript facsimile, as “A Transit to Narcissus,” in 1978). Even as a student, he thought of himself as a professional writer, and from the day that Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, in December, 1941, he had wanted to write a big book about the war. He was sent for basic training to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where many of the men were from Pennsylvania, the South, and the Upper Midwest. Mailer was from middle-class Jewish Brooklyn; he had landed in the great working-class Gentile world, and was eager to observe. He canvassed the recruits about their sex lives, taking notes on a yellow legal pad. (He discovered that many of them did not believe in foreplay.) Mailer knew that tough Jews served in the war, including criminals, louts, and bitterly determined, hardworking men, but he was without physical skills. He had never worked a thresher, or manhandled heavy goods into a truck, or tinkered with Dad’s jalopy.

When Norman Mailer was inducted into the Army, in March, 1944, he was a freshly married twenty-one-year-old Harvard graduate, a slight young man of five feet eight inches and a hundred and thirty-five pounds. In the previous few years, he had published some stories and written a play and two novels (one of them published, in a typescript facsimile, as “A Transit to Narcissus,” in 1978). Even as a student, he thought of himself as a professional writer, and from the day that Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, in December, 1941, he had wanted to write a big book about the war. He was sent for basic training to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where many of the men were from Pennsylvania, the South, and the Upper Midwest. Mailer was from middle-class Jewish Brooklyn; he had landed in the great working-class Gentile world, and was eager to observe. He canvassed the recruits about their sex lives, taking notes on a yellow legal pad. (He discovered that many of them did not believe in foreplay.) Mailer knew that tough Jews served in the war, including criminals, louts, and bitterly determined, hardworking men, but he was without physical skills. He had never worked a thresher, or manhandled heavy goods into a truck, or tinkered with Dad’s jalopy.

In early January, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur landed with an enormous invasion force on Luzon, the largest of the Philippine islands; Mailer, after waiting in a troopship, went ashore a few weeks later. He was thrown as a rifleman into the 112th Cavalry Regiment, out of Texas. The 112th had been in combat in the Pacific for more than a year, and many men in the unit had died. Mailer described those who remained as a little crazy, and physically messed up—some with open ulcers from jungle rot. The Texans were joined by men from other parts of the country, some of them bar fighters and casual anti-Semites (not by theory but by habit). “I didn’t open my mouth for six months in that outfit,” he later said.

More here.

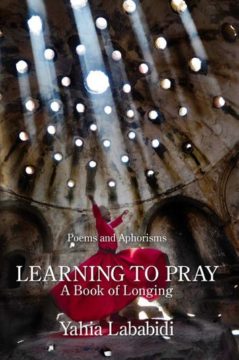

Is Sufi poetry the new religion?

Vinita Agrawal in Frontline:

The twin books of Egyptian poet Yahia Lababidi— Learning to Pray: A Book of Longing and Desert Songs, published in 2021 and 2022, respectively—uphold the Sufi tradition that was critical in shaping the imagery, symbolism, metaphors, tropes, and indeed the world view, of classical Sufi poetry and portray mercy with a pluralistic vision by upholding an expression of love above all divides. Lababidi does this by the clean magic of his language, relatable imagery and fine craft.

The twin books of Egyptian poet Yahia Lababidi— Learning to Pray: A Book of Longing and Desert Songs, published in 2021 and 2022, respectively—uphold the Sufi tradition that was critical in shaping the imagery, symbolism, metaphors, tropes, and indeed the world view, of classical Sufi poetry and portray mercy with a pluralistic vision by upholding an expression of love above all divides. Lababidi does this by the clean magic of his language, relatable imagery and fine craft.

In Lababidi’s poetry, one is brought face to face with the knowledge that it is love and love alone which can address all discord, whether spiritual or material, and help us find peace. This peace is beyond the fabric of political peace or peace between nations as we know it—it is the sublime bliss of becoming one with God, the cessation of inner turmoil and the sweet melding of the heart with the divine. And is that not the fundamental teaching of all religions?

More here.

Friday Poem

Being Called a Faggot While Walking the Road to Clemson, South Carolina

The honeysuckle dew slick

& sweet this morning

& only an empty Wendy’s cup

thrown to ditch

& the truck passing

(& it is almost always

a truck) slows just

to roll down

the window & O

I wish they could smell

this & O I wish

I could quit

them driving

so fast & missing

this honeysuckle, so dew-

sweet this morning.

by D. Gilson

from Split This Rock, 2015

The Deadly Lack of Imagination in the Democratic Party

Thomas Frank in the New York Times:

Democrats did so well, in part, because a conservative Supreme Court handed them a political gift by overturning Roe v. Wade and Republicans ran a group of dreadful celebrity Senate candidates.

Democrats did so well, in part, because a conservative Supreme Court handed them a political gift by overturning Roe v. Wade and Republicans ran a group of dreadful celebrity Senate candidates.

The reality of the triumph, however, is that liberals are back to stalemate. Stalemate, that is, with an opponent that has been radicalizing for 50 years. An opponent that continually produces outrageous fire-breathing extremists, then supplants them with a new crop when the zealotry of the first bunch has worn off. It feels like the cycle is endless. But there is an answer to this problem, if we can just think beyond the limits of our current political imagination.

Ever since I started paying attention, virtually all the country’s political dynamism has been located on the right. They brought us Prop 13, the Reagan revolution, the Gingrich revolution, the Tea Party and Trumpism, each successive explosion securing some new tax cut or making some grand deregulatory thrust before exhausting itself and leaving the stage. That there will be another explosion soon, picking up where the last one left off, is almost a certainty.