Month: December 2022

20th-Century America’s Greatest Landscape Architect

Penelope Rowlands at The American Scholar:

After Bunny’s arrangement with Paul was established, she went on to flower artistically. Partly schooled by John Fowler, of the London interior design firm of Colefax & Fowler, she cast a spell on all seven of her residences—including ones in Nantucket, Washington, D.C., and New York City. In this phase, too, she championed and collaborated with a long line of gay visual artists. These relationships took the form of “violent crushes”; each of them, for her, was a kind of romance. And one, the gifted French jewelry designer Jean Schlumberger—”the black cat,” she called him—is rumored to have been her lover in the early 1950s. He escorted her to Paris, where she attended the haute couture collections for the first time. Once “perilously close to dowdy,” Griswold writes, Bunny was transformed. She became a style icon, seemingly overnight, thanks to her new, romance-tinged friendships with two famed fashion designers, Cristóbal Balenciaga and Hubert de Givenchy. The latter brought Bunny into Paris’s haut monde. She purchased an apartment on the Avenue Foch and basked in the attention of a chic new crowd she called her “French family.” The courtly Givenchy steered Bunny toward one of her most celebrated projects—her impeccable restoration of the 1678 Potager de Roi, Louis XIV’s kitchen garden at Versailles, which had long fallen into desuetude.

After Bunny’s arrangement with Paul was established, she went on to flower artistically. Partly schooled by John Fowler, of the London interior design firm of Colefax & Fowler, she cast a spell on all seven of her residences—including ones in Nantucket, Washington, D.C., and New York City. In this phase, too, she championed and collaborated with a long line of gay visual artists. These relationships took the form of “violent crushes”; each of them, for her, was a kind of romance. And one, the gifted French jewelry designer Jean Schlumberger—”the black cat,” she called him—is rumored to have been her lover in the early 1950s. He escorted her to Paris, where she attended the haute couture collections for the first time. Once “perilously close to dowdy,” Griswold writes, Bunny was transformed. She became a style icon, seemingly overnight, thanks to her new, romance-tinged friendships with two famed fashion designers, Cristóbal Balenciaga and Hubert de Givenchy. The latter brought Bunny into Paris’s haut monde. She purchased an apartment on the Avenue Foch and basked in the attention of a chic new crowd she called her “French family.” The courtly Givenchy steered Bunny toward one of her most celebrated projects—her impeccable restoration of the 1678 Potager de Roi, Louis XIV’s kitchen garden at Versailles, which had long fallen into desuetude.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Untitled

1.

My family arrived here in a Marxist tradition

My mother immediately filled the house with Santa knick-knacks

Weighed the pros and cons of the plastic Christmas tree

as if the problem were hers

During the day she distinguished between long and short vowels

as if the sounds that came out of her mouth

could wash the olive oil from her skin

My mother let bleach run through her syntax

On the other side of punctuation her syllables became whiter

than a winter in Norrland

My mother built us a future consisting of quantity of life

In the suburban basement she lined up canned goods

as if preparing for a war

In the evenings she searched for recipes and peeled potatoes

As if it were her history inscribed

in the Jansson’s temptation casserole

To think that I sucked at those breasts

To think that she put her barbarism in my mouth

2.

My mother said: You are a dreamer born to turn straight eyes aslant

My mother said: If you could regard the circumstances as extenuating

you would let me off easier

My mother said: Never underestimate the trouble people will take

to formulate truths possible for them to bear

My mother said: You were not fit to live even from the start

3.

My mother said: From the division of cells

from a genetic material

from your father’s head

But not from me

My father said: From the clash of civilizations

from a fundamental antagonism

from my tired head

But not from her

by Athena Farrokhzad

from Versopolis

translation: Jennifer Hayashida

2022 Breakthrough of the year: A new space telescope makes a spectacular debut

Daniel Clery in Science:

On 11 July, in a live broadcast from the White House, U.S. President Joe Biden unveiled the first image from what he called a “miraculous” new space telescope. Along with millions of people around the world, he marveled at a crush of thousands of galaxies, some seen as they were 13 billion years ago. “It’s hard to even fathom,” Biden said.

On 11 July, in a live broadcast from the White House, U.S. President Joe Biden unveiled the first image from what he called a “miraculous” new space telescope. Along with millions of people around the world, he marveled at a crush of thousands of galaxies, some seen as they were 13 billion years ago. “It’s hard to even fathom,” Biden said.

Not many telescopes get introduced by the president, but JWST, the gold-plated wunderkind of astronomy built by NASA with the help of the European and Canadian space agencies, deserves that honor. It is the most complex science mission ever put into space and at $10 billion the most expensive. And it did not come easy. Its construction on Earth took 20 years and faced multiple setbacks. New perils came during the telescope’s monthlong, 1.5-million-kilometer journey into space, as its giant sunshield unfurled and its golden mirror blossomed. Engineers ticked off a total of 344 critical steps—any one of which could have doomed the mission had they gone wrong.

More here.

A Means to an End: The intertwined history of education, history, and patriotism in the United States

Michael Hattem in Lapham’s Quarterly:

In 1788, as the young republic was trying to establish itself under the new Constitution, Noah Webster wrote, “Americans, unshackle your minds, and act like independent beings…you have an empire to raise…and a national character to establish.” “To effect these great objects,” he continued, “it is necessary to frame a liberal plan of policy and build it on a broad system of education.” After the War of Independence ended, Webster published several best-selling readers and grammatical texts “calculated particularly for American schools.” These books incorporated many now-familiar stories from the United States’ colonial and revolutionary past, chosen for their “noble, just, and independent sentiments of liberty and patriotism” with the hope that education might “transfuse them into the breasts of the rising generation.” From the very beginnings of the United States, education, history, and patriotism have been fundamentally intertwined.

In 1788, as the young republic was trying to establish itself under the new Constitution, Noah Webster wrote, “Americans, unshackle your minds, and act like independent beings…you have an empire to raise…and a national character to establish.” “To effect these great objects,” he continued, “it is necessary to frame a liberal plan of policy and build it on a broad system of education.” After the War of Independence ended, Webster published several best-selling readers and grammatical texts “calculated particularly for American schools.” These books incorporated many now-familiar stories from the United States’ colonial and revolutionary past, chosen for their “noble, just, and independent sentiments of liberty and patriotism” with the hope that education might “transfuse them into the breasts of the rising generation.” From the very beginnings of the United States, education, history, and patriotism have been fundamentally intertwined.

Education in the United States underwent its first great expansion in the decades between the Revolution and the Civil War. The revolutionary generation had few models of public education. Until then, education had been limited almost entirely to elite white males, who were instructed in Latin and Greek (required for admission to college) at young ages in grammar schools.

More here.

The Short Shelf Life of “Longtermism”

by Tim Sommers

Despite what you might have heard, it almost certainly wasn’t Yogi Berra or Samuel Goldwyn who said it. It may be an old Danish Proverb. But it is probably a remark made by someone in the Danish Parliament between 1937-1938, recorded without attribution in the voluminous autobiography of one Karl Kristian Steincke. It being:

“It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.”

This is one reason you should probably be much less concerned with the end of the world than longtermists like Sam Bankman-Fried, Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and William MacAskill are – or claim to be.

Here’s a slightly more accurate, if more pretentious, way of putting it, this time unequivocally from Wittgenstein:

“When we think of the world’s future, we always mean the destination it will reach if it keeps going in the direction we can see it going in now; it does not occur to us that its path is not a straight line but a curve, constantly changing direction.”

That’s the moral. Here’s the story.

It was not MacAskill, Hilary Greaves, or Nick Bostrom – much less Bankman-Fried – that came up with longtermism, perhaps the most controversial element of the most controversial and visible philosophical and moral movement of the twenty-first century, “effective altruism.” Longtermism, specifically, is the view that we owe the future a certain priority over the present, especially when it comes to existential risks, like nuclear war, pandemics, artificial intelligence, and nanotechnology. Read more »

Human Flourishing in the Age of Machines

by Jonathan Kujawa

Recently some colleagues and I were out to lunch. It was our University’s “Dead Week.” This is the week before finals when students are in a last-minute rush to finish projects and study for exams, and faculty are planning how to wind up their courses and beginning to draft their final exams.

My colleagues and I joked that writing a final exam is basically an analog version of the Turing Test: You try to craft questions that can distinguish between the students who actually understand the material and those who “solve” problems by being skilled at pattern recognition and applying rote algorithms.

Coincidently, around the time of this lunch, OpenAI released ChatGPT. As 3QD readers no doubt have heard, ChatGPT is a large language model which was trained on a significant chunk of text in 2021. Using that text, it developed a model of which words and phrases most often follow one another. Using that model, ChatGPT then writes replies to prompts submitted by the user. The results are equally amazing and banal. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. Cactus In My Window.

Sughra Raza. Cactus In My Window.

Digital photograph.

Seen and Heard

by Chris Horner

A choice of ‘cultural things’ I enjoyed in 2022 and which you might like, too. Some were from well before this year, but discovered by me in ’22. Novel, non fiction, concert, recording, exhibition. Here we go:

- Novel: The Odd Women – George Gissing.

This is the kind of novel which when read makes you wonder why it isn’t better known and more widely celebrated. The late 19th century saw a wave of plays and novels dealing with ‘the New Woman’ – the educated, worryingly independent, vote-seeking, bicycling women of the late Victorian/Edwardian age. Examples include Victoria Cross’s Anna Lombard (1901), Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) Many of these were predictable rubbish: marriage or death solves everything. Exceptions among plays are Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, and among novels HG Wells’ Ann Veronica (1909), but it’s the Gissing that is really the winner among novels. Gissing avoids most of the cliches and stereotypes and produces a narrative that is genuinely absorbing and a set of themes and characters one remembers long after the book is put down. Gissing is an odd fish: he has real empathy for the plight of the poor and the rejected (both here and in The Nether World and his more famous New Grub Street), but has an ‘official’ conservative ideology which, when he lets it, blocks him from being able to imagine how the agency of working class or (as here) mainly lower middle class women might work for their liberation. In this he isn’t alone: many great novelists have said more through their literature than their ‘official’ beliefs ought to allow them to do (think of Dostoyevsky) In The Odd Women, he largely lets his imagination take him places his philosophy could never encompass. The book emerges as a fascinating account of the situation of the ‘superfluous’ women of the 1890s – and shows how they either succumbed to or overcame the world that seemed to have no place for them. Read more »

This is the kind of novel which when read makes you wonder why it isn’t better known and more widely celebrated. The late 19th century saw a wave of plays and novels dealing with ‘the New Woman’ – the educated, worryingly independent, vote-seeking, bicycling women of the late Victorian/Edwardian age. Examples include Victoria Cross’s Anna Lombard (1901), Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) Many of these were predictable rubbish: marriage or death solves everything. Exceptions among plays are Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, and among novels HG Wells’ Ann Veronica (1909), but it’s the Gissing that is really the winner among novels. Gissing avoids most of the cliches and stereotypes and produces a narrative that is genuinely absorbing and a set of themes and characters one remembers long after the book is put down. Gissing is an odd fish: he has real empathy for the plight of the poor and the rejected (both here and in The Nether World and his more famous New Grub Street), but has an ‘official’ conservative ideology which, when he lets it, blocks him from being able to imagine how the agency of working class or (as here) mainly lower middle class women might work for their liberation. In this he isn’t alone: many great novelists have said more through their literature than their ‘official’ beliefs ought to allow them to do (think of Dostoyevsky) In The Odd Women, he largely lets his imagination take him places his philosophy could never encompass. The book emerges as a fascinating account of the situation of the ‘superfluous’ women of the 1890s – and shows how they either succumbed to or overcame the world that seemed to have no place for them. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Ahead to the Past: Parsing 2022

by Brooks Riley

Looking back at the year gone by is the tedious task of news editors who aim to make sense of the senseless, find connections where none exist, and leave us with a neat package of nostalgia to file away in our collective memory. I’ve never been partial to such wrap-ups, with their facile interpretations of events, their mining for relevance where none exists.

Another thing that makes such year-end assessments so difficult, is the necessary conjunction of events of varying levels of gravitas: Imagine talking about Twitter king Elon Musk in the same breath as Vladimir Putin, mentally blending images of a digital town meeting with a security council meeting at the Kremlin. One shudders at the juxtaposition of wounded infants in Ukraine with the trivial issue of buccal fat surgery. After a while, all newsworthy events in a given year begin to appear surreal, existing side by side inside separate vacuums that bump into each other like bumper cars at an amusement park.

Part of me doesn’t care much for the immediate past. Part of me wants to get on with it, whatever ‘it’ is. Slowly but surely, I’ve evolved from being a participant in life to being an observer of it. From my modest command center I gaze out at the world through a digital lens and try to understand what’s going on. It’s becoming much harder to do that.

As an observer now, I am less tolerant of the rampant vanities let loose on social media. I find many more public figures ridiculous, and many viral trends simply absurd. (Is it me, or is it them?) My inner curmudgeon stretches its limbs like a newborn, even as it is forced to coexist with my inner teenager who, for some reason, is still alive and kicking. Read more »

Monday Photo: Jupiter Rising

Washington Square, December

by Ethan Seavey

It’s halfway through the month of December and New York is filled with pine boughs and small yellow bells and horse-drawn carriages and scarves. We are seated on the edge of the fountain in Washington Square Park, though this time of year the water has been shut off. A group of five skateboarders are practicing jumps in the large basin. We just bought a pre-rolled joint from one of the stands in the park, of which there are many. But we only buy from one of them. Weed is legal in the city now, but it’s not legally sold, so it can be questionable, and you never want “questionable” when you’re prone to paranoia. We trust the woman who runs this stand, though, because we know where she buys it and she has a rainbow flag on the front of her table.

It’s halfway through the month of December and New York is filled with pine boughs and small yellow bells and horse-drawn carriages and scarves. We are seated on the edge of the fountain in Washington Square Park, though this time of year the water has been shut off. A group of five skateboarders are practicing jumps in the large basin. We just bought a pre-rolled joint from one of the stands in the park, of which there are many. But we only buy from one of them. Weed is legal in the city now, but it’s not legally sold, so it can be questionable, and you never want “questionable” when you’re prone to paranoia. We trust the woman who runs this stand, though, because we know where she buys it and she has a rainbow flag on the front of her table.

So we sit queerly on the edge of a queer fountain smoking some queer weed. We talk about something, I don’t know, maybe how Halloween is a gay holiday but Christmas is a straight one and we have fatigue. A New York Christmas is not one of comfort or much joy. Starting in November, there’s a pressure in the air that pushes you to believe you need to do a long checklist of items. You need to see Rockefeller Center, you need to go to this small pop-up and that department store extravaganza. You need to go to the holiday markets at Union Square, where people shuffle by long lines of other people waiting to shop at little stands, and the ones at Bryant Park, which you never see because Union Square was such a nightmare. A New York Christmas is hearing tinny bells played on speakers for weeks and drunk Santas racing from bar to bar. A New York Christmas is one where you can only find silence and darkness when you’re tucked away into your tiny apartment.

Certainly there is magic in the season as well and I am rarely as gleeful as when I have a quiet Christmas moment with friends. But it is finals week and I can’t see past a devastating head cold. Read more »

On Indices of First Lines

by Eric Bies

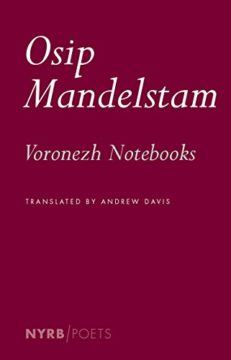

There I sat (or stood (or, who knows, hovered )), trying to read Osip Mandelstam…

(…not, to be sure, the early Stone poems; not the later Poems poems; not the Egyptian Stamp, not even the essay on Dante, but his final literary effort: cobbled together from the vantage of that characteristically Soviet brand of exile-cum-vacation, about 500 klicks south of Moscow), in this case, the Andrew Davis translation of the Voronezh Notebooks.

As I sat, etc., and perused the table of contents, I noticed that the book contained—in addition to its eighty-nine numbered poems and introduction—an index of first lines.

I remembered the first time I’d noticed such an index. The memory of the encounter was fresh enough—not quite far enough back to not resound so readily with the powerful shame of my nervousness in the company of poems. I remembered how, once, attempting to temper this skittishness, I’d picked out a couple of battered volumes of Auden and Coleridge, friendly clothbound entries into the Everyman’s Library Pocket Poets Series that are with me still. Now as then they remain neat, tidy, approachable: they were, for a reader who’d made the frosty acquaintance of Eliot and Pound, poetry on training wheels. And instrumentally, at the back of them, one could and still can make alphabetical reference to each poem by the words with which it starts. So, too, I remember noticing this then: that that Auden began with “A cloudless night like this” and ended up “Wrapped in a yielding air, beside.”

Later, but not too much later, I took notice (if not any interest in the real utility) of similar indices appended as yet more backmatter to yet other editions of bound selections, collections, and completions of the poetry that continued to unman me. Read more »

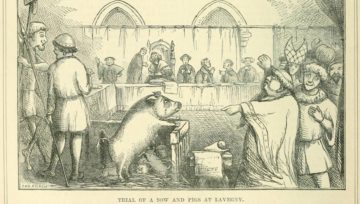

If animals are persons, should they bear criminal responsibility?

Ed Simon in Psyche:

If you were an animal in need of legal representation in early 16th-century Burgundy – a horse that had trampled its owner, a sow that had attacked the farmer’s son, a goat caught in flagrante delicto with the neighbour boy – then the best lawyer in the realm was Barthélemy de Chasseneuz. Though he’d later author the first major text on French customary law, become an eloquent defender of the rights of religious minorities, and be elected parliamentary representative for Dijon, Chasseneuz is most remembered for winning an acquittal on behalf of a group of rats put on trial for eating through the province’s barley crop in 1522. Edward Payson Evans, an American linguist whose book The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals (1906) remains the standard work on the subject, explains that Chasseneuz was ‘forced to employ all sorts of legal shifts and chicane, dilatory pleas and other technical objections,’ including the argument that the rats couldn’t be forced to take the stand because their lives were at risk from the feral cats in the town of Autun, ‘hoping thereby to find some loophole in the meshes of the law through which the accused might escape’ like, well, rats. They were found not guilty.

If you were an animal in need of legal representation in early 16th-century Burgundy – a horse that had trampled its owner, a sow that had attacked the farmer’s son, a goat caught in flagrante delicto with the neighbour boy – then the best lawyer in the realm was Barthélemy de Chasseneuz. Though he’d later author the first major text on French customary law, become an eloquent defender of the rights of religious minorities, and be elected parliamentary representative for Dijon, Chasseneuz is most remembered for winning an acquittal on behalf of a group of rats put on trial for eating through the province’s barley crop in 1522. Edward Payson Evans, an American linguist whose book The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals (1906) remains the standard work on the subject, explains that Chasseneuz was ‘forced to employ all sorts of legal shifts and chicane, dilatory pleas and other technical objections,’ including the argument that the rats couldn’t be forced to take the stand because their lives were at risk from the feral cats in the town of Autun, ‘hoping thereby to find some loophole in the meshes of the law through which the accused might escape’ like, well, rats. They were found not guilty.

Dismissing animal trials as just another backwards practice of a primitive time is to our intellectual detriment, not only because it imposes a pernicious presentism on the past, but also because it’s worth considering whether or not the broader implications of such a ritual don’t have something to tell us about different ways of understanding nonhuman consciousness, and the rights that our fellow creatures deserve.

More here.

Experts Debate the Risks of Made-to-Order DNA

Michael Schulson in Undark:

If DNA is the code of life, then outfits like GeneArt are printshops — they synthesize custom strands of DNA and ship them to scientists, who can use the DNA to make a yeast cell glow in the dark, or to create a plastic-eating bacterium, or to build a virus from scratch. Today there are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of companies selling genes, offering DNA at increasingly low prices. (If DNA resembles a long piece of text, rates today are often lower than 10 cents per letter; at this rate, the genetic material necessary to begin constructing an influenza virus would cost less than $1,500.) And new benchtop technologies — essentially, portable gene printers — promise to make synthetic DNA even more widely available.

If DNA is the code of life, then outfits like GeneArt are printshops — they synthesize custom strands of DNA and ship them to scientists, who can use the DNA to make a yeast cell glow in the dark, or to create a plastic-eating bacterium, or to build a virus from scratch. Today there are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of companies selling genes, offering DNA at increasingly low prices. (If DNA resembles a long piece of text, rates today are often lower than 10 cents per letter; at this rate, the genetic material necessary to begin constructing an influenza virus would cost less than $1,500.) And new benchtop technologies — essentially, portable gene printers — promise to make synthetic DNA even more widely available.

But, since at least the 2000s, the field has been shadowed by fears that someone will use these services to cause harm — in particular, to manufacture a deadly virus and use it to commit an act of bioterrorism.

Meanwhile, the United States imposes few security regulations on synthetic DNA providers. It’s perfectly legal to make a batch of genes from Ebola or smallpox and ship it to a U.S. address, no questions asked — although actually creating the virus from that genetic material may be illegal under laws governing the possession of certain pathogens.

More here.

Designing the Future in Palestine

Noura Erakat in the Boston Review:

Vivien Sansour is excited about wheat. More than 10,000 years ago, she explains, visionaries in the fertile crescent domesticated it and began to transform it into the croissants, pitas, and baguettes that feed the world today. Sansour studies seeds as a way to “design new things the way that [her] ancestors did.” In 2014 she founded the Heirloom Seed Library and then spent the next four years searching for heirloom varieties for preservation and propagation. Many of these seeds, all indigenous to Palestine, are threatened because of colonial regulation of Palestinian lands and lives. Israel has forced other species onto Palestinian farmers for the sake of efficiency and scale, though it maintains one of the largest heirloom seed libraries at the Arava Institute. While the institute maintains an experimental orchard, the seeds themselves are off-limits to farmers. Sansour insists that while the settler sovereign “took our seeds away from us, they don’t have the story and the system of knowledge associated with the seed.”

Vivien Sansour is excited about wheat. More than 10,000 years ago, she explains, visionaries in the fertile crescent domesticated it and began to transform it into the croissants, pitas, and baguettes that feed the world today. Sansour studies seeds as a way to “design new things the way that [her] ancestors did.” In 2014 she founded the Heirloom Seed Library and then spent the next four years searching for heirloom varieties for preservation and propagation. Many of these seeds, all indigenous to Palestine, are threatened because of colonial regulation of Palestinian lands and lives. Israel has forced other species onto Palestinian farmers for the sake of efficiency and scale, though it maintains one of the largest heirloom seed libraries at the Arava Institute. While the institute maintains an experimental orchard, the seeds themselves are off-limits to farmers. Sansour insists that while the settler sovereign “took our seeds away from us, they don’t have the story and the system of knowledge associated with the seed.”

More here.

Mark Blyth: An Assessment of Our Economic Future

Why Dickens Haunts Us

Maureen Dowd in The New York Times:

WASHINGTON — I had always been a bah humbug sort of person about Christmas.

WASHINGTON — I had always been a bah humbug sort of person about Christmas.

It seemed like a season of stress, as my parents scrambled to find the money to buy presents for five kids and have a big feast. I didn’t like the materialism or the mawkishness. Why should there be one week of the year when we were all supposed to be Hallmark happy? “You’re weird,” my mother told me.

Then I took a course on Charles Dickens at Columbia University with the estimable Prof. James Eli Adams, and I began to fathom the magic. As Dickens said in his sketch, “A Christmas Tree,” published in his journal “Household Words” in 1850, “Oh, now all common things become uncommon and enchanted to me.” His biographer Peter Ackroyd wrote that “Dickens can be said to have almost single-handedly created the modern idea of Christmas.” Christmas morally radicalized Dickens. The disparity between the circumstances and fates of different people offended Dickens in the Christmas season. For him, it was a time to think about what we owe one another, how we live with one another; a time to have a proper sense of outrage about inequality and injustice, and to think about the past, present and future and how much they have to do with each other; a time to consider the good values we’ve thrown away and the bad values — selfishness, egotism, social snobbery, condescension and the worship of money — that infiltrate the heart. Dickens became an outsider looking in when his middle-class life got disrupted by cold, grinding reality: His father went to debtors’ prison and, at 12, Dickens had to leave school to work in a bootblacking factory in London.

…As Mitch Glazer, who co-wrote “Scrooged,” the hilarious 1988 movie with Bill Murray, put it: “Dickens hits us with the setup: regret, loss, mistakes, missed love, wasted life, and then the punchline: ‘It’s not too late!’ In every version from his novella to Mr. Magoo to ours, I always get emotional when Scrooge is reborn.” Dickens has taught me that it’s not too late to focus on the sweet memories, like the time my mom somehow bought me a doll’s kitchen I longed for that my parents couldn’t afford, or the way she would be aghast if we didn’t wear red and green.

The magic is there, if you look. So on this Christmas, as Tiny Tim said, God bless us, every one!

More here.

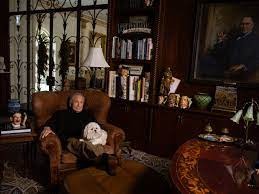

Dick Cavett Takes a Few Questions

Michael Schulman in The New Yorker:

To revisit “The Dick Cavett Show,” which ran late night on ABC from 1969 to 1975 (and in various other incarnations before and after), is to enter a time capsule—not just because of Cavett’s guests, who included aging Hollywood doyennes (Bette Davis, Katharine Hepburn), rock legends in their chaotic prime (Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix), and squabbling intellectuals (Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer), but because Cavett’s free-flowing yet informed interviewing style is all but absent from contemporary television. Late-night shows are now tightly scripted affairs, where celebrities can plug a new movie, tell a rehearsed anecdote, and maybe get roped into a lip-synch battle. But Cavett gently prodded his subjects into revealing themselves. Though he was pegged as the “intellectual” late-night host, he resisted the label. He was a creature of show business: spontaneous, witty, and interested in everything.

To revisit “The Dick Cavett Show,” which ran late night on ABC from 1969 to 1975 (and in various other incarnations before and after), is to enter a time capsule—not just because of Cavett’s guests, who included aging Hollywood doyennes (Bette Davis, Katharine Hepburn), rock legends in their chaotic prime (Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix), and squabbling intellectuals (Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer), but because Cavett’s free-flowing yet informed interviewing style is all but absent from contemporary television. Late-night shows are now tightly scripted affairs, where celebrities can plug a new movie, tell a rehearsed anecdote, and maybe get roped into a lip-synch battle. But Cavett gently prodded his subjects into revealing themselves. Though he was pegged as the “intellectual” late-night host, he resisted the label. He was a creature of show business: spontaneous, witty, and interested in everything.

Cavett’s interviews with the likes of George Harrison, Orson Welles, Lily Tomlin, and Richard Pryor have racked up millions of views on YouTube, providing a unique window into a raw, freewheeling, contentious time. A Nebraska native who went to Yale and got his start writing for the late-night hosts Jack Paar and Johnny Carson (before becoming Carson’s competition), Cavett presided over an era split between culture and counterculture, squares and hippies. He wasn’t quite either, but he was somehow at home with both. Two of his most frequent guests, each of whom became a close friend, were Groucho Marx and Muhammad Ali—who represented either pole. On December 27th, American Masters will air a documentary about the former, “Groucho & Cavett,” the filmmaker Robert S. Bader’s follow-up to “Ali & Cavett: The Tale of the Tapes.”

More here.