Peter E. Gordon in The New Statesman:

Peter E. Gordon in The New Statesman:

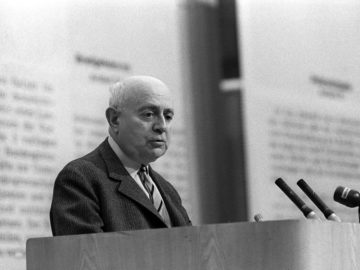

Minima Moralia is a work of exile. Published just over 70 years ago in 1951, the greater share of it was written at the conclusion of the Second World War, when its German-born author Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno was living in Los Angeles County, not far from other artists and intellectuals who had the good fortune to escape the Third Reich. “The violence that expelled me,” he explained, left him with an enduring sense of guilt at the very fact of his survival. The book’s subtitle, “Reflections from Damaged Life”, is a record of this unhealed wound, a bitter confession that even to write about individual experience suggests a complicity with “unspeakable collective events”. But Adorno worked at the trauma and made of it an irritant for thinking, sand for the pearls of insight that would fill each page. It is the most personal book he ever wrote, and even at the highest peaks of abstraction, it does not efface its origins in autobiography. Not unlike the Essais by the 16th-century humanist Michel de Montaigne, Adorno’s book is not only a series of philosophical experiments but also an exercise in self-portraiture. What Adorno calls “subjective experience” must serve as a permanent element for all criticism if it does not wish to contribute to the further destruction of humanity.

How can we classify an intellectual who abhorred classification? Critical of all group loyalty and always distancing himself from his social surroundings, Adorno was a cosmopolitan intellectual who carried his erudition on his back as the only possession that mattered.

More here.