Adam Kirsch in The New Criterion:

Eighty years ago, in the fall of 1941, the musical Best Foot Forward opened on Broadway. Written by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane, who would go on to write the songs for the classic film Meet Me in St. Louis a few years later, Best Foot Forward is not a classic—it’s a piece of fluff about a prep-school boy who invites a Hollywood actress to be his prom date, to the annoyance of his actual girlfriend. But it ran on Broadway for almost a year and then was turned into a movie, with Lucille Ball as the starlet, that’s still worth watching.

Eighty years ago, in the fall of 1941, the musical Best Foot Forward opened on Broadway. Written by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane, who would go on to write the songs for the classic film Meet Me in St. Louis a few years later, Best Foot Forward is not a classic—it’s a piece of fluff about a prep-school boy who invites a Hollywood actress to be his prom date, to the annoyance of his actual girlfriend. But it ran on Broadway for almost a year and then was turned into a movie, with Lucille Ball as the starlet, that’s still worth watching.

A standout number is “The Three Bs,” in which three high-school girls tell Harry James’s big band what not to play: “I never wanna hear Johann Sebastian Bach/ And I don’t wanna listen to Ludwig Beethoven/ And I don’t give a hoot for old Johannes Brahms.” Instead, the three Bs they demand are “the barrelhouse, the boogie-woogie, and the blues,” popular styles of the day that are each sampled in the song.

Aside from being fun, the song also captures an interesting transitional moment in American culture. By 1941, pop had already taken over from classical as the musical lingua franca, the sound everybody wanted to hear.

More here.

In late summer of 1976, two colleagues at Oxford University Press, Michael Rodgers and Richard Charkin, were discussing a book on evolution soon to be published. It was by a first-time author, a junior zoology don in town, and had been given an initial print run of 5,000 copies. As the two publishers debated the book’s fate, Charkin confided that he doubted it would sell more than 2,000 copies. In response, Rodgers, who was the editor who had acquired the manuscript, suggested a bet whereby he would pay Charkin £1 for every 1,000 copies under 5,000, and Charkin was to buy Rodgers a pint of beer for every 1,000 copies over 5,000. By now, the book is one of OUP’s most successful titles, and it has sold more than a million copies in dozens of languages, spread across four editions. That book was Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene, and Charkin is ‘holding back payment in the interests of [Rodgers’s] health and wellbeing’.

In late summer of 1976, two colleagues at Oxford University Press, Michael Rodgers and Richard Charkin, were discussing a book on evolution soon to be published. It was by a first-time author, a junior zoology don in town, and had been given an initial print run of 5,000 copies. As the two publishers debated the book’s fate, Charkin confided that he doubted it would sell more than 2,000 copies. In response, Rodgers, who was the editor who had acquired the manuscript, suggested a bet whereby he would pay Charkin £1 for every 1,000 copies under 5,000, and Charkin was to buy Rodgers a pint of beer for every 1,000 copies over 5,000. By now, the book is one of OUP’s most successful titles, and it has sold more than a million copies in dozens of languages, spread across four editions. That book was Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene, and Charkin is ‘holding back payment in the interests of [Rodgers’s] health and wellbeing’. I moved to Karachi in the aftermath of riots, arriving to smashed shop windows and the smell of burning tires. It was 2012 and the city had been engulfed by protests against a YouTube video that made offensive statements about the Prophet Muhammad. The city’s few remaining cinemas had been attacked, and churches had taken extra security precautions, lest the mob hold Pakistan’s Christians accountable for the crimes of the American filmmakers. The scale of destruction was disproportionate to the offence itself. I was a Londoner moving to my mother’s hometown, a place I had visited only once since childhood. This was an immediate introduction to the discontent that bubbled beneath the surface of the city, always ready to erupt into violence.

I moved to Karachi in the aftermath of riots, arriving to smashed shop windows and the smell of burning tires. It was 2012 and the city had been engulfed by protests against a YouTube video that made offensive statements about the Prophet Muhammad. The city’s few remaining cinemas had been attacked, and churches had taken extra security precautions, lest the mob hold Pakistan’s Christians accountable for the crimes of the American filmmakers. The scale of destruction was disproportionate to the offence itself. I was a Londoner moving to my mother’s hometown, a place I had visited only once since childhood. This was an immediate introduction to the discontent that bubbled beneath the surface of the city, always ready to erupt into violence. Cryptocurrencies have emerged as one of the most captivating, yet head-scratching, investments in the world. They soar in value. They crash. They’ll change the world, their fans claim, by displacing traditional currencies like the dollar, rupee or ruble. They’re named after

Cryptocurrencies have emerged as one of the most captivating, yet head-scratching, investments in the world. They soar in value. They crash. They’ll change the world, their fans claim, by displacing traditional currencies like the dollar, rupee or ruble. They’re named after  Purple morning glories creep and sprawl against a white fence, embracing a sculpture of sorts, wooden arms akimbo; a blue plastic bin flipped over. One can almost hear the crunch of the photographer’s foot against the dried grass. The photographs of Sue Palmer Stone exist somewhere between the extremes of exuberance and decay, fragility and strength, loss and playfulness.

Purple morning glories creep and sprawl against a white fence, embracing a sculpture of sorts, wooden arms akimbo; a blue plastic bin flipped over. One can almost hear the crunch of the photographer’s foot against the dried grass. The photographs of Sue Palmer Stone exist somewhere between the extremes of exuberance and decay, fragility and strength, loss and playfulness. Before

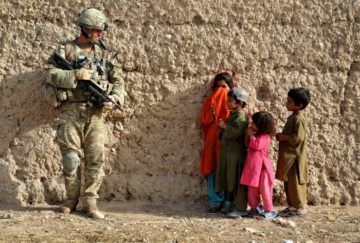

Before  Thomas Meaney in the LRB (Photo by

Thomas Meaney in the LRB (Photo by  Wolfgang Streeck in Sidecar (Photo by

Wolfgang Streeck in Sidecar (Photo by  Faisal Devji in Boston Review:

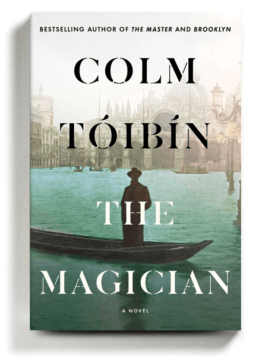

Faisal Devji in Boston Review: In those diaries, Mann frankly discussed his sexual interest in men, an interest that remained coded in his fiction. In “The Magician,” a subtle and substantial new novel about Mann’s life, Colm Toibin writes that, were Goebbels to get his hands on the diaries, he would Oscar Wilde the eminent author, transforming “the reputation of Thomas Mann from great German writer to a name that was a byword for scandal.”

In those diaries, Mann frankly discussed his sexual interest in men, an interest that remained coded in his fiction. In “The Magician,” a subtle and substantial new novel about Mann’s life, Colm Toibin writes that, were Goebbels to get his hands on the diaries, he would Oscar Wilde the eminent author, transforming “the reputation of Thomas Mann from great German writer to a name that was a byword for scandal.” The message Martha is actually sending, the reason large numbers of American women count watching her a comforting and obscurely inspirational experience, seems not very well understood. There has been a flurry of academic work done on the cultural meaning of her success (in the summer of 1998, the New York Times reported that “about two dozen scholars across the United States and Canada” were producing such studies as “A Look at Linen Closets: Liminality, Structure and Anti-Structure in Martha Stewart Living” and locating “the fear of transgression” in the magazine’s “recurrent images of fences, hedges and garden walls”), but there remains, both in the bond she makes and in the outrage she provokes, something unaddressed, something pitched, like a dog whistle, too high for traditional textual analysis. The outrage, which reaches sometimes startling levels, centers on the misconception that she has somehow tricked her admirers into not noticing the ambition that brought her to their attention. To her critics, she seems to represent a fraud to be exposed, a wrong to be righted. “She’s a shark,” one declares in Salon. “However much she’s got, Martha wants more. And she wants it her way and in her world, not in the balls-out boys’ club realms of real estate or technology, but in the delicate land of doily hearts and wedding cakes.”

The message Martha is actually sending, the reason large numbers of American women count watching her a comforting and obscurely inspirational experience, seems not very well understood. There has been a flurry of academic work done on the cultural meaning of her success (in the summer of 1998, the New York Times reported that “about two dozen scholars across the United States and Canada” were producing such studies as “A Look at Linen Closets: Liminality, Structure and Anti-Structure in Martha Stewart Living” and locating “the fear of transgression” in the magazine’s “recurrent images of fences, hedges and garden walls”), but there remains, both in the bond she makes and in the outrage she provokes, something unaddressed, something pitched, like a dog whistle, too high for traditional textual analysis. The outrage, which reaches sometimes startling levels, centers on the misconception that she has somehow tricked her admirers into not noticing the ambition that brought her to their attention. To her critics, she seems to represent a fraud to be exposed, a wrong to be righted. “She’s a shark,” one declares in Salon. “However much she’s got, Martha wants more. And she wants it her way and in her world, not in the balls-out boys’ club realms of real estate or technology, but in the delicate land of doily hearts and wedding cakes.” Vaccines don’t last forever. This is by design: Like many of the microbes they mimic, the contents of the shots stick around only as long as it takes the body to eliminate them, a tenure on the order of

Vaccines don’t last forever. This is by design: Like many of the microbes they mimic, the contents of the shots stick around only as long as it takes the body to eliminate them, a tenure on the order of  In the spring of 1880, in the midst of what felt like a political tipping point, a new monument dedicated to the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin was unveiled in Moscow. Alexander II’s Great Reforms of the 1860s — including the emancipation of the serfs — had not satisfied the appetites of radicals for change. Most alarming to moderate Russians were the women who had begun joining the ranks of the self-described Nihilists. They smoked cigarettes, cut their hair short, preferred Feuerbach to romance novels and spurned marriage in favor of careers in science and medicine (or, occasionally, terrorism).

In the spring of 1880, in the midst of what felt like a political tipping point, a new monument dedicated to the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin was unveiled in Moscow. Alexander II’s Great Reforms of the 1860s — including the emancipation of the serfs — had not satisfied the appetites of radicals for change. Most alarming to moderate Russians were the women who had begun joining the ranks of the self-described Nihilists. They smoked cigarettes, cut their hair short, preferred Feuerbach to romance novels and spurned marriage in favor of careers in science and medicine (or, occasionally, terrorism).