Alison Flood in The Guardian:

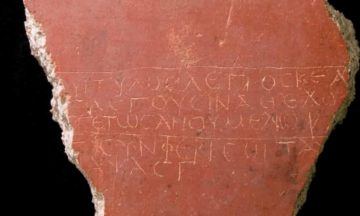

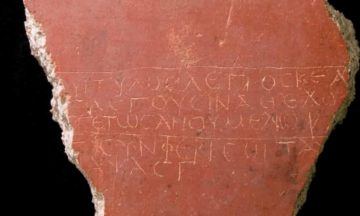

For Taylor Swift, the “haters gonna hate”, but she’ll just “shake it off”. Now research by a Cambridge academic into a little-known ancient Greek text bearing much the same sentiment – “They say / What they like / Let them say it / I don’t care” – is set to cast a new light on the history of poetry and song.

For Taylor Swift, the “haters gonna hate”, but she’ll just “shake it off”. Now research by a Cambridge academic into a little-known ancient Greek text bearing much the same sentiment – “They say / What they like / Let them say it / I don’t care” – is set to cast a new light on the history of poetry and song.

The anonymous text, which concludes with the lines “Go on, love me / It does you good”, was popular across the eastern Roman empire in the second century, and has been found inscribed on 20 gemstones and as a graffito in Cartagena, Spain. After comparing all known versions of the text for the first time, classics professor Tim Whitmarsh spotted that it used a different form of metre than usually found in ancient Greek poetry, employing stressed and unstressed syllables. Whitmarsh said that “stressed poetry”, the ancestor of all modern poetry and song, was unknown before the fifth century, when it began to be used in Byzantine Christian hymns. Before the emergence of stressed poetry, poetry was quantitative – based on syllable length.

“We’ve known for a long time that there was popular poetry in ancient Greek, but a lot of what survives takes a similar form to traditional high poetics. This poem, on the other hand, points to a distinct and thriving culture, primarily oral, which fortunately for us in this case also found its way on to a number of gemstones,” said Whitmarsh. “You didn’t need specialist poets to create this kind of musicalised language, and the diction is very simple, so this was clearly a democratising form of literature. We’re getting an exciting glimpse of a form of oral pop culture that lay under the surface of classical culture.” Whitmarsh believes the verse, with its lines of four syllables, with a strong accent on the first and a weaker on the third, could represent a “missing link” between the lost world of ancient Mediterranean oral poetry and song, and the more modern forms that we know today. It is, he says, so far unparalleled in the classical world.

More here.

It’s a truism that language is integral to identity. So when our relationship with it changes, complications quickly accrue: Do we become someone different in another tongue? Is that all down to culture and context, or is there something inherent in a language that affects who we feel ourselves to be? And what happens when we start our lives speaking one language but then switch to another?

It’s a truism that language is integral to identity. So when our relationship with it changes, complications quickly accrue: Do we become someone different in another tongue? Is that all down to culture and context, or is there something inherent in a language that affects who we feel ourselves to be? And what happens when we start our lives speaking one language but then switch to another?

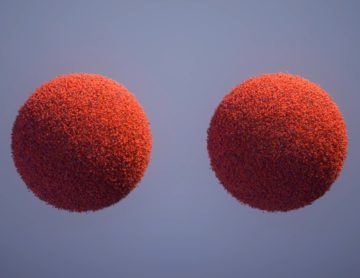

Imagine two friends hiking in the woods. They grow hungry and decide to split an apple, but half an apple feels meager. Then one of them remembers one of the strangest ideas she’s ever encountered. It’s a mathematical theorem involving infinity that makes it possible, at least in principle, to turn one apple into two.

Imagine two friends hiking in the woods. They grow hungry and decide to split an apple, but half an apple feels meager. Then one of them remembers one of the strangest ideas she’s ever encountered. It’s a mathematical theorem involving infinity that makes it possible, at least in principle, to turn one apple into two. The world is only starting to grapple with how profound the artificial-intelligence revolution will be. AI technologies will create waves of progress in critical infrastructure, commerce, transportation, health, education, financial markets, food production, and environmental sustainability. Successful adoption of AI will drive economies, reshape societies, and determine which countries set the rules for the coming century.

The world is only starting to grapple with how profound the artificial-intelligence revolution will be. AI technologies will create waves of progress in critical infrastructure, commerce, transportation, health, education, financial markets, food production, and environmental sustainability. Successful adoption of AI will drive economies, reshape societies, and determine which countries set the rules for the coming century. Throughout history, the idea of islands where women rule has been part mythological wish fulfilment, part male fantasy – and part cultural-geographical reality. In 2017 I moved to Orkney, an archipelago still dominated, as all of Britain once was, by its monumental neolithic architecture. Early one spring morning I visited the chambered

Throughout history, the idea of islands where women rule has been part mythological wish fulfilment, part male fantasy – and part cultural-geographical reality. In 2017 I moved to Orkney, an archipelago still dominated, as all of Britain once was, by its monumental neolithic architecture. Early one spring morning I visited the chambered  “I

“I To be even remotely plausible, a computer model of the human mind must warp — and restrict — our commonsense definitions of intelligence, knowledge, understanding, and action. Larson discusses the renowned computer scientist Stuart Russell, who

To be even remotely plausible, a computer model of the human mind must warp — and restrict — our commonsense definitions of intelligence, knowledge, understanding, and action. Larson discusses the renowned computer scientist Stuart Russell, who  “We never said the welfare state is a substitute for socialism.” This staple of Harrington’s lecture tours had a flipside, his retort to old-school socialists: “Any idiot can nationalize a bank.” He said both things frequently after Mitterrand retreated. Harrington relied on his core message: bureaucratic collectivism is an unavoidable reality. The question is whether it can be wrested into a democratic and ethically decent form. Freedom will survive the ascendance of globalized markets and corporations only if it achieves economic democracy. Harrington had long argued that the market should operate within a plan, but in the mid-1980s his actual position shifted to the opposite. He conceived planning within a market framework on the model of Swedish and German social democracy—solidarity wages, full employment, co-determination, and collective worker funds. To many critics that smacked of selling out socialism. He replied: “To think that ‘socialization’ is a panacea is to ignore the socialist history of the twentieth century, including the experience of France under Mitterrand. I am for worker- and community-controlled ownership and for an immediate and practical program for full employment which approximates as much of that ideal as possible. No more. No less.”

“We never said the welfare state is a substitute for socialism.” This staple of Harrington’s lecture tours had a flipside, his retort to old-school socialists: “Any idiot can nationalize a bank.” He said both things frequently after Mitterrand retreated. Harrington relied on his core message: bureaucratic collectivism is an unavoidable reality. The question is whether it can be wrested into a democratic and ethically decent form. Freedom will survive the ascendance of globalized markets and corporations only if it achieves economic democracy. Harrington had long argued that the market should operate within a plan, but in the mid-1980s his actual position shifted to the opposite. He conceived planning within a market framework on the model of Swedish and German social democracy—solidarity wages, full employment, co-determination, and collective worker funds. To many critics that smacked of selling out socialism. He replied: “To think that ‘socialization’ is a panacea is to ignore the socialist history of the twentieth century, including the experience of France under Mitterrand. I am for worker- and community-controlled ownership and for an immediate and practical program for full employment which approximates as much of that ideal as possible. No more. No less.” In April, the New York Times

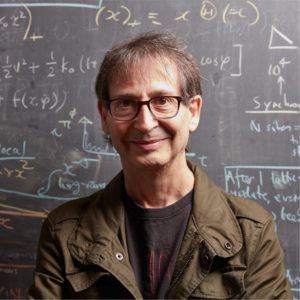

In April, the New York Times  Physics is extremely good at describing simple systems with relatively few moving parts. Sadly, the world is not like that; many phenomena of interest are complex, with multiple interacting parts and interesting things happening at multiple scales of length and time. One area where the techniques of physics overlap with the multi-scale property of complex systems is in the study of phase transitions, when a composite system transitions from one phase to another. Nigel Goldenfeld has made important contributions to the study of phase transitions in their own right (and mathematical techniques for dealing with them), and has also been successful at leveraging that understanding to study biological systems, from the genetic code to the tree of life.

Physics is extremely good at describing simple systems with relatively few moving parts. Sadly, the world is not like that; many phenomena of interest are complex, with multiple interacting parts and interesting things happening at multiple scales of length and time. One area where the techniques of physics overlap with the multi-scale property of complex systems is in the study of phase transitions, when a composite system transitions from one phase to another. Nigel Goldenfeld has made important contributions to the study of phase transitions in their own right (and mathematical techniques for dealing with them), and has also been successful at leveraging that understanding to study biological systems, from the genetic code to the tree of life. Salar Abdoh: I’ve read my share of books and articles over the years about Afghanistan and talked to people who spent stretches of time there, but it’s no exaggeration to say that I’ve never come across one person who has more in-the-field experience than you have about a land that few understand but many weigh in on, far too irresponsibly.

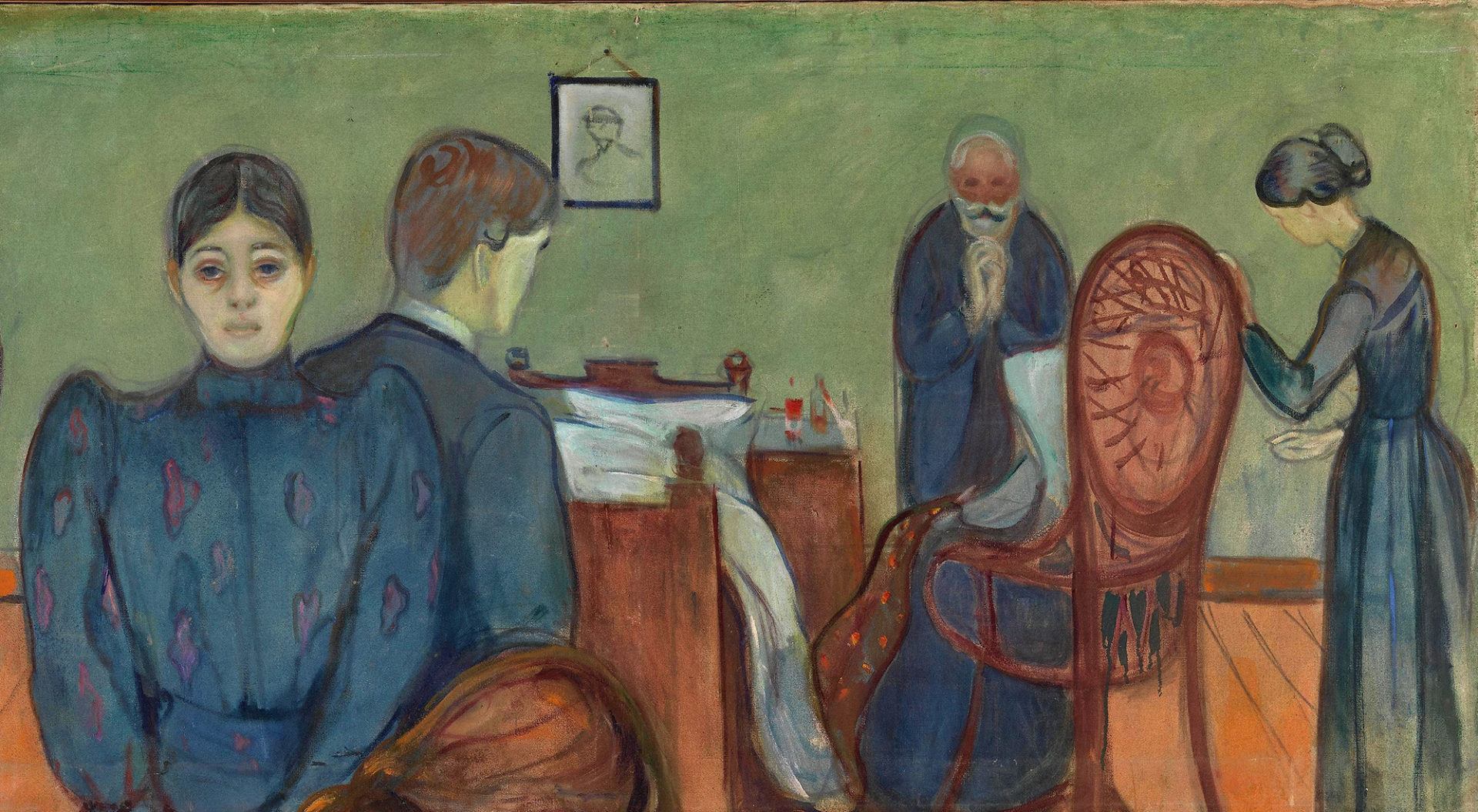

Salar Abdoh: I’ve read my share of books and articles over the years about Afghanistan and talked to people who spent stretches of time there, but it’s no exaggeration to say that I’ve never come across one person who has more in-the-field experience than you have about a land that few understand but many weigh in on, far too irresponsibly. JÓZEF CZAPSKI was a reserve officer in the Polish army when German and Soviet forces invaded his country in September 1939. His unit surrendered to the Soviets toward the end of that month. In “Memories of Starobielsk,” the 40-page essay that gives this collection, translated by Alissa Valles, its title, Czapski tells how he and his comrades were deceived by the promise that they would be sent through neutral territory to France, from where they could continue the fight against the Germans. Instead, they were marched eastward as prisoners of war, over the Soviet frontier:

JÓZEF CZAPSKI was a reserve officer in the Polish army when German and Soviet forces invaded his country in September 1939. His unit surrendered to the Soviets toward the end of that month. In “Memories of Starobielsk,” the 40-page essay that gives this collection, translated by Alissa Valles, its title, Czapski tells how he and his comrades were deceived by the promise that they would be sent through neutral territory to France, from where they could continue the fight against the Germans. Instead, they were marched eastward as prisoners of war, over the Soviet frontier: Simone de Beauvoir’s rucksack invariably contained a candle, an alarm clock, a copy of the local Guide Bleu, a Michelin map, and a felt-covered water bottle filled with red wine. She hadn’t always walked with a rucksack: when she arrived in Marseilles, age twenty-three, to take up her first teaching post, she’d walked with a basket. It was here, among the mountains, valleys, and cliffs of Provence, that a passion for solitary rambles and “communion with nature” first took hold of her. “I derived a satisfaction I had never known in all the rush and bustle of my Paris life,” she wrote in her memoir.

Simone de Beauvoir’s rucksack invariably contained a candle, an alarm clock, a copy of the local Guide Bleu, a Michelin map, and a felt-covered water bottle filled with red wine. She hadn’t always walked with a rucksack: when she arrived in Marseilles, age twenty-three, to take up her first teaching post, she’d walked with a basket. It was here, among the mountains, valleys, and cliffs of Provence, that a passion for solitary rambles and “communion with nature” first took hold of her. “I derived a satisfaction I had never known in all the rush and bustle of my Paris life,” she wrote in her memoir. For Taylor Swift, the “haters gonna hate”, but she’ll just “shake it off”. Now research by a Cambridge academic into a little-known ancient Greek text bearing much the same sentiment – “They say / What they like / Let them say it / I don’t care” – is set to cast a new light on the history of poetry and song.

For Taylor Swift, the “haters gonna hate”, but she’ll just “shake it off”. Now research by a Cambridge academic into a little-known ancient Greek text bearing much the same sentiment – “They say / What they like / Let them say it / I don’t care” – is set to cast a new light on the history of poetry and song. Twenty years ago, precisely on 9-11-2001, I was booked to fly out from NYC to Tehran. All flights were cancelled, so I witnessed the aftermath of the gruesome attack here in Manhattan. I wrote about what I saw and what I felt, drawing on what I then understood about the world. It was hardly a deep understanding especially about the Middle East, Iran, or Islamism, I admit. (That I was woefully unprepared to navigate the tumultuous waters of Middle Eastern geopolitics – which after 9-11 began churning with a new intensity – was something I would learn the hard way in the decade to come.) My essay “September 11: An Iranian In New York” was published in English in November after reaching Tehran. It was then published in Persian in one of Tehran’s main newspaper’s magazine edition. I have appended the Persian at the end this post.

Twenty years ago, precisely on 9-11-2001, I was booked to fly out from NYC to Tehran. All flights were cancelled, so I witnessed the aftermath of the gruesome attack here in Manhattan. I wrote about what I saw and what I felt, drawing on what I then understood about the world. It was hardly a deep understanding especially about the Middle East, Iran, or Islamism, I admit. (That I was woefully unprepared to navigate the tumultuous waters of Middle Eastern geopolitics – which after 9-11 began churning with a new intensity – was something I would learn the hard way in the decade to come.) My essay “September 11: An Iranian In New York” was published in English in November after reaching Tehran. It was then published in Persian in one of Tehran’s main newspaper’s magazine edition. I have appended the Persian at the end this post.