From Harvard Magazine:

“WORRYING SEEMS ABOUT as necessary as breathing these days,” President Lawrence J. Bacow remarked last Friday in his address at the tenth annual Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching (HILT) conference. “Global challenges abound, and efforts to address them will have to be based in deep considerations of equity and justice, of community and humanity. How do we prepare our students to undertake that work? How can we do a better job as teachers, as scholars, as leaders, of putting our own work in as broad a context as possible?” These questions opened the conference, this year titled “Tackling Global Challenges from the Harvard Classroom and Beyond” and attended by more than 300 Harvard faculty members and academic leaders. The conference is designed to create a University-wide dialogue about teaching and learning innovation among Harvard’s professors, senior leaders, academic professionals, and students. (Read about the 2020 conference here.)

“WORRYING SEEMS ABOUT as necessary as breathing these days,” President Lawrence J. Bacow remarked last Friday in his address at the tenth annual Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching (HILT) conference. “Global challenges abound, and efforts to address them will have to be based in deep considerations of equity and justice, of community and humanity. How do we prepare our students to undertake that work? How can we do a better job as teachers, as scholars, as leaders, of putting our own work in as broad a context as possible?” These questions opened the conference, this year titled “Tackling Global Challenges from the Harvard Classroom and Beyond” and attended by more than 300 Harvard faculty members and academic leaders. The conference is designed to create a University-wide dialogue about teaching and learning innovation among Harvard’s professors, senior leaders, academic professionals, and students. (Read about the 2020 conference here.)

This year’s event—again conducted virtually via Zoom—encouraged Harvard educators to reflect on their experience teaching remotely during a pandemic that “exacerbated issues” like social and healthcare inequality “that have existed in society for many, many years,” said panelist and senior lecturer in molecular and cellular biology Alain Viel. Undergraduate courses have returned to in-person instruction, but “We can’t ignore what happened during the last 17 months,” said Bharat N. Anand, vice provost for advances in learning. Those 17 months—marked by the pandemic, remote teaching, protests against systemic racism and police brutality, and economic hardship for millions of people—made it clear to educators that their students will enter a changed world after graduation.

Graduate School of Education (HGSE) dean Bridget Terry Long noted that as students spread around the world into a wide variety of communities, Harvard was no longer “far removed in Cambridge in the ivory tower.” With both the state of the world and the global reach of remote teaching in mind, the conference posed one central question: “How can we best prepare students to address global challenges in thoughtful and creative ways?”

More here.

Dave Eggers’s newest book, The Every, is about a near-future mega-monopoly clearly based on Amazon, Facebook, and Google. It’s his follow-up to The Circle, and follows a different protagonist, Delaney, who seeks to destroy the company from the inside.

Dave Eggers’s newest book, The Every, is about a near-future mega-monopoly clearly based on Amazon, Facebook, and Google. It’s his follow-up to The Circle, and follows a different protagonist, Delaney, who seeks to destroy the company from the inside.

In the question to understand the biology of life, we are (so far) limited to what happened here on Earth. That includes the diversity of biological organisms today, but also its entire past history. Using modern genomic techniques, we can extrapolate backward to reconstruct the genomes of primitive organisms, both to learn about life’s early stages and to guide our ideas about life elsewhere. I talk with astrobiologist Betül Kaçar about paleogenomics and our prospects for finding (or creating!) life in the universe.

In the question to understand the biology of life, we are (so far) limited to what happened here on Earth. That includes the diversity of biological organisms today, but also its entire past history. Using modern genomic techniques, we can extrapolate backward to reconstruct the genomes of primitive organisms, both to learn about life’s early stages and to guide our ideas about life elsewhere. I talk with astrobiologist Betül Kaçar about paleogenomics and our prospects for finding (or creating!) life in the universe. “Leave? Certainly not. This Brit is staying” wrote journalist Stephen Vines in July 1997. Vines had given up his full-time position at the Observer in London to be stationed in Hong Kong on a part-time basis in 1987. At the time of the Handover, Vines had been living and working in Hong Kong as a journalist and businessman for ten years. He had faith in the people of Hong Kong, in the energy and audacity of the city. He believed that it was “foolish to jump before being pushed,” referring to those who had made plans to leave the city before the governance of the territory was returned to China. Vines kept his resolution and stayed in Hong Kong for another 24 years, constantly reporting on the business, finance, and politics of this city for a wide range of local and international media outlets. In 2021, he paid homage to the people of Hong Kong with his new book, Defying the Dragon: Hong Kong and the World’s Largest Dictatorship. In August, two months after the book’s publication, Vines ended his 34-year-long sojourn in the city and departed for London.

“Leave? Certainly not. This Brit is staying” wrote journalist Stephen Vines in July 1997. Vines had given up his full-time position at the Observer in London to be stationed in Hong Kong on a part-time basis in 1987. At the time of the Handover, Vines had been living and working in Hong Kong as a journalist and businessman for ten years. He had faith in the people of Hong Kong, in the energy and audacity of the city. He believed that it was “foolish to jump before being pushed,” referring to those who had made plans to leave the city before the governance of the territory was returned to China. Vines kept his resolution and stayed in Hong Kong for another 24 years, constantly reporting on the business, finance, and politics of this city for a wide range of local and international media outlets. In 2021, he paid homage to the people of Hong Kong with his new book, Defying the Dragon: Hong Kong and the World’s Largest Dictatorship. In August, two months after the book’s publication, Vines ended his 34-year-long sojourn in the city and departed for London. “WORRYING SEEMS ABOUT

“WORRYING SEEMS ABOUT  In 2018, Jennifer Culverson was at home in Charleston, South Carolina, when she was violently assaulted by her then-boyfriend. (Culverson’s name has been changed to protect her identity.) Her attacker overpowered her and battered her head against the floor with such force that it caused a traumatic brain injury. In the weeks and months that followed, Culverson couldn’t walk or get out of bed. She had trouble putting words together and her speech was slurred.

In 2018, Jennifer Culverson was at home in Charleston, South Carolina, when she was violently assaulted by her then-boyfriend. (Culverson’s name has been changed to protect her identity.) Her attacker overpowered her and battered her head against the floor with such force that it caused a traumatic brain injury. In the weeks and months that followed, Culverson couldn’t walk or get out of bed. She had trouble putting words together and her speech was slurred. Reading between the lines, I think she learned pretty much the same thing a lot of the rest of us learned during the grim years of the last decade. Of the fifty-odd biases discovered by Kahneman, Tversky, and their successors, forty-nine are cute quirks, and one is destroying civilization. This last one is confirmation bias – our tendency to interpret evidence as confirming our pre-existing beliefs instead of changing our minds. This is the bias that explains why your political opponents continue to be your political opponents, instead of converting to your obviously superior beliefs. And so on to religion, pseudoscience, and all the other scourges of the intellectual world.

Reading between the lines, I think she learned pretty much the same thing a lot of the rest of us learned during the grim years of the last decade. Of the fifty-odd biases discovered by Kahneman, Tversky, and their successors, forty-nine are cute quirks, and one is destroying civilization. This last one is confirmation bias – our tendency to interpret evidence as confirming our pre-existing beliefs instead of changing our minds. This is the bias that explains why your political opponents continue to be your political opponents, instead of converting to your obviously superior beliefs. And so on to religion, pseudoscience, and all the other scourges of the intellectual world. The author of some of the most acclaimed works of the modern literary canon, including The Trial (1925), The Castle (1926), and The Metamorphosis (1915), was drawing and sketching extensively before he published a single word. Brod, Kafka’s closest friend and literary executor, held on to as many of the drawings as he could. When Kafka died in 1924, Brod famously disregarded the author’s instructions that everything was “to be burned, completely and unread.” He spent the rest of his life publishing and promoting Kafka’s work, and when he fled the Nazi occupation of Prague in 1939 for Palestine, he took Kafka’s papers and drawings with him. He published a small selection of the pictures in his biographical writings on Kafka and sold two of them to the Albertina in Vienna. Others appeared in Kafka’s diaries, today at the Bodleian Library at Oxford, which Brod edited for publication in 1948. This is all the world has known until now of Kafka’s art — scarcely 40 or so drawings and sketches from what was once a far larger corpus, much of it lost or destroyed, and the rest mostly invisible to the public until this year.

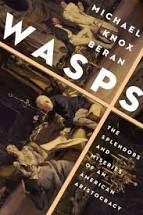

The author of some of the most acclaimed works of the modern literary canon, including The Trial (1925), The Castle (1926), and The Metamorphosis (1915), was drawing and sketching extensively before he published a single word. Brod, Kafka’s closest friend and literary executor, held on to as many of the drawings as he could. When Kafka died in 1924, Brod famously disregarded the author’s instructions that everything was “to be burned, completely and unread.” He spent the rest of his life publishing and promoting Kafka’s work, and when he fled the Nazi occupation of Prague in 1939 for Palestine, he took Kafka’s papers and drawings with him. He published a small selection of the pictures in his biographical writings on Kafka and sold two of them to the Albertina in Vienna. Others appeared in Kafka’s diaries, today at the Bodleian Library at Oxford, which Brod edited for publication in 1948. This is all the world has known until now of Kafka’s art — scarcely 40 or so drawings and sketches from what was once a far larger corpus, much of it lost or destroyed, and the rest mostly invisible to the public until this year. Michael Knox Beran begins his exploration brutally by telling us that the WASPs are finished, quite dead. Edie Sedgwick, one of Andy Warhol’s muses, was the last desperate gasp of the WASPs, reduced to being brought to prominence (of a kind) by someone from Pittsburgh and then cruelly abandoned. She died of a drug overdose in 1971. Her father, Fuzzy, was bad enough, removing himself to California, where he turned his vast private estate into a version of the Playboy Mansion. The book goes backwards from there but things don’t get any better. Early on comes this extraordinary sentence: ‘There is … great difficulty in writing about people whose time has passed, who were bathed in the lukewarm bath of snobbery, who, with flashes of insight, were largely mediocre.’

Michael Knox Beran begins his exploration brutally by telling us that the WASPs are finished, quite dead. Edie Sedgwick, one of Andy Warhol’s muses, was the last desperate gasp of the WASPs, reduced to being brought to prominence (of a kind) by someone from Pittsburgh and then cruelly abandoned. She died of a drug overdose in 1971. Her father, Fuzzy, was bad enough, removing himself to California, where he turned his vast private estate into a version of the Playboy Mansion. The book goes backwards from there but things don’t get any better. Early on comes this extraordinary sentence: ‘There is … great difficulty in writing about people whose time has passed, who were bathed in the lukewarm bath of snobbery, who, with flashes of insight, were largely mediocre.’ Two years ago, to prepare for an unusual photo shoot, a team of scientists plucked the wings from thousands of fruit flies and pressed each flake of iridescent tissue between glass plates. As often as not, the wing tore or folded, or an air pocket or errant piece of dust got trapped along with it, ruining the sample. Fly wings are “not like Saran wrap,” said

Two years ago, to prepare for an unusual photo shoot, a team of scientists plucked the wings from thousands of fruit flies and pressed each flake of iridescent tissue between glass plates. As often as not, the wing tore or folded, or an air pocket or errant piece of dust got trapped along with it, ruining the sample. Fly wings are “not like Saran wrap,” said  Rationality is uncool. To describe someone with a slang word for the cerebral, like nerd, wonk, geek, or brainiac, is to imply they are terminally challenged in hipness. For decades, Hollywood screenplays and rock-song lyrics have equated joy and freedom with an escape from reason. “A man needs a little madness or else he never dares cut the rope and be free,”

Rationality is uncool. To describe someone with a slang word for the cerebral, like nerd, wonk, geek, or brainiac, is to imply they are terminally challenged in hipness. For decades, Hollywood screenplays and rock-song lyrics have equated joy and freedom with an escape from reason. “A man needs a little madness or else he never dares cut the rope and be free,”  For centuries, humans complained about the weather. In 1848, the Smithsonian Institution decided to do something about it. Weather conditions had been considered to be either God’s will or explainable only by homespun nostrums like “Clear moon, frost soon” or by observing, say, the behavior of ants, which don’t like rain. The Farmer’s Almanac promised readers more accurate forecasts when it debuted in 1818, but even those predictions were determined by a “secret formula.” And still are.

For centuries, humans complained about the weather. In 1848, the Smithsonian Institution decided to do something about it. Weather conditions had been considered to be either God’s will or explainable only by homespun nostrums like “Clear moon, frost soon” or by observing, say, the behavior of ants, which don’t like rain. The Farmer’s Almanac promised readers more accurate forecasts when it debuted in 1818, but even those predictions were determined by a “secret formula.” And still are. As a young lieutenant, Daniel Kahneman was asked to improve the Israeli army’s haphazard process of assessing capabilities among combat-eligible recruits.

As a young lieutenant, Daniel Kahneman was asked to improve the Israeli army’s haphazard process of assessing capabilities among combat-eligible recruits. The medications, developed to treat and prevent viral infections in people and animals, work differently depending on the type. But they can be engineered to boost the immune system to fight infection, block receptors so viruses can’t enter healthy cells, or lower the amount of active virus in the body.

The medications, developed to treat and prevent viral infections in people and animals, work differently depending on the type. But they can be engineered to boost the immune system to fight infection, block receptors so viruses can’t enter healthy cells, or lower the amount of active virus in the body. DNA plays a major role, indeed a starring role, in generating socioeconomic inequality in the United States, according to Kathryn Paige Harden, a behavioral geneticist at the University of Texas. In her provocative new book, The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality, she contends that our genes predispose us to getting more or less education, which then largely determines our place in the social order. This argument isn’t new. It has appeared perhaps most notoriously in Arthur Jensen’s infamous 1969 article in the Harvard Educational Review (

DNA plays a major role, indeed a starring role, in generating socioeconomic inequality in the United States, according to Kathryn Paige Harden, a behavioral geneticist at the University of Texas. In her provocative new book, The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality, she contends that our genes predispose us to getting more or less education, which then largely determines our place in the social order. This argument isn’t new. It has appeared perhaps most notoriously in Arthur Jensen’s infamous 1969 article in the Harvard Educational Review ( C

C