by Fabio Tollon

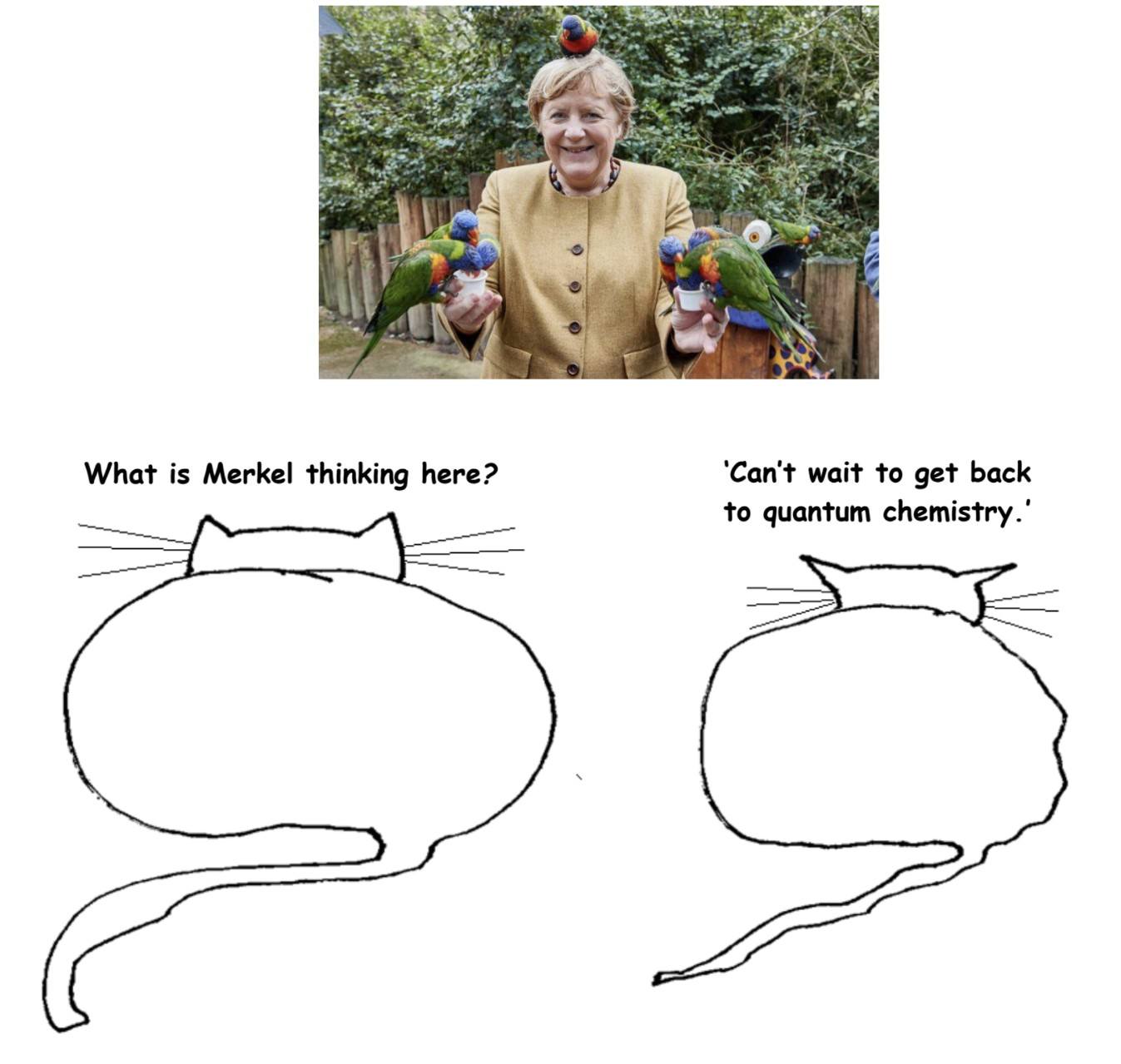

One of the cornerstones good of science is that its results furnish us with an objective understanding of the world. That is, science, when done correctly, tells us how the world is, independently of how we might feel the world to be (based, for example, on our values or commitments). It is thus central to science, and its claims to objectivity, that values do not override facts. An important feature of this view of science is the distinction between epistemic and non-epistemic values. Simply, epistemic values are those which would seem to make for good science: external coherence, explanatory power, parsimony, etc. Non-epistemic values, on the other hand, concern things like our value judgements, biases, and preferences. In order for science to work well, so the story goes, it should only be epistemic values that come to matter when we assess the legitimacy of a given scientific theory (this is often termed the “value-free ideal”). Thus, a central presupposition underpinning this value-free ideal is that we can in fact mark a distinction between epistemic and non-epistemic values Unfortunately, as with most things in philosophy, things are not that simple.

The first thing to note are the various ways that the value-free ideal plays out in the context of discovery, justification, and application. With respect to the context of discovery, it doesn’t seem to matter if we find that non-epistemic values are operative. While decisions about funding lines, the significance we attach to various theories, and the choice of questions we might want to investigate are all important insofar as they influence where we might choose to look for evidence, they do not determine whether the theories we come up with are valid or not.

Similarly, in the context of application, we could invoke the age-old is-ought distinction: scientific theories cannot justify value-laden beliefs. For example, even if research shows that taller people are more intelligent, it would not follow that taller people are more valuable than shorter people. Such a claim would depend on the value that one ascribes to intelligence beforehand. Therefore, how we go about applying scientific theories is influenced by non-epistemic values, and this is not necessarily problematic.

Thus, in both the context of validation and the context of discovery, we find non-epistemic values to be operative. This, however, is not seen as much of a problem, so long as these values do not “leak” into the context of justification, as it is here that science’s claims to objectivity are preserved. Is this really possible in practice though? Read more »

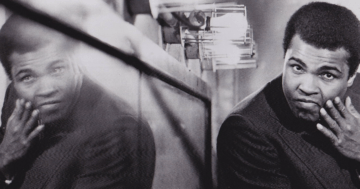

There’s power in watching Ali exact his revenge against Ernie Terrell, who had refused to call him by his Muslim name prior to their fight, punishing Terrell in the ring as he repeatedly taunts him: “What’s my name?” As the essayist Gerald Early says, “It was a sign that a new kind of Black athlete had appeared, a whole new kind of Black consciousness had appeared—it was a whole new kind of Black male dispensation that had come about as a result of that fight. That fight to me and I think for many other young Black people such as myself at the time was a turning point.”

There’s power in watching Ali exact his revenge against Ernie Terrell, who had refused to call him by his Muslim name prior to their fight, punishing Terrell in the ring as he repeatedly taunts him: “What’s my name?” As the essayist Gerald Early says, “It was a sign that a new kind of Black athlete had appeared, a whole new kind of Black consciousness had appeared—it was a whole new kind of Black male dispensation that had come about as a result of that fight. That fight to me and I think for many other young Black people such as myself at the time was a turning point.”

It’s National Inclusion Week when we all come together to ‘celebrate everyday inclusion in all its forms’. This year’s theme is ‘unity’ where ‘thousands of inclusioneers worldwide’ are being encouraged to ‘take action to be #UnitedForInclusion.’ In the bewildering world of identity politics, however, there is one group of excluded individuals you won’t be hearing much about. As a demographic, they suffer from all kinds of discrimination and yet social justice activists seem uninterested in their plight. Unlike oppressed minorities, this particular group may be in the majority and yet they garner little in the way of sympathy from anyone, barring their mums, perhaps.

It’s National Inclusion Week when we all come together to ‘celebrate everyday inclusion in all its forms’. This year’s theme is ‘unity’ where ‘thousands of inclusioneers worldwide’ are being encouraged to ‘take action to be #UnitedForInclusion.’ In the bewildering world of identity politics, however, there is one group of excluded individuals you won’t be hearing much about. As a demographic, they suffer from all kinds of discrimination and yet social justice activists seem uninterested in their plight. Unlike oppressed minorities, this particular group may be in the majority and yet they garner little in the way of sympathy from anyone, barring their mums, perhaps. People who have psychologically mediated physical symptoms always fear being accused of feigning illness. I knew that one of the reasons Dr. Olssen was desperate for me to provide a brain-related explanation for the children’s condition was to help them escape such an accusation. She also knew that a brain disorder had a better chance of being respected than a psychological disorder. To refer to resignation syndrome as stress induced would lessen the seriousness of the children’s condition in people’s minds. It is the way of the world that the length of time a person spends as sick, immobile, and unresponsive is less impressive if it doesn’t come with a corresponding change on a brain scan.

People who have psychologically mediated physical symptoms always fear being accused of feigning illness. I knew that one of the reasons Dr. Olssen was desperate for me to provide a brain-related explanation for the children’s condition was to help them escape such an accusation. She also knew that a brain disorder had a better chance of being respected than a psychological disorder. To refer to resignation syndrome as stress induced would lessen the seriousness of the children’s condition in people’s minds. It is the way of the world that the length of time a person spends as sick, immobile, and unresponsive is less impressive if it doesn’t come with a corresponding change on a brain scan.

The well-known counterintuitive Monty Hall problem continues to baffle people if the emails I receive are any indication. A meta-problem is to understand why so many people are unconvinced by the various solutions. Sometimes people even cite the large number of the unconvinced as proof that the solution is a matter of real controversy, just as in politics an inconvenient fact, such as the ubiquity of Covid-19, is obscured by fake controversies.

The well-known counterintuitive Monty Hall problem continues to baffle people if the emails I receive are any indication. A meta-problem is to understand why so many people are unconvinced by the various solutions. Sometimes people even cite the large number of the unconvinced as proof that the solution is a matter of real controversy, just as in politics an inconvenient fact, such as the ubiquity of Covid-19, is obscured by fake controversies.

It had been a long time since I thought about lawns. I don’t mean in a grand philosophical sense, or the stoned contemplation of a single blade of grass. I mean thought about them at all. Before moving to Mississippi we had lived in Vancouver for 13 years, where we felt lucky to have a place to store our toothbrushes and maybe an extra pair of slacks; we really hit the jackpot when we acquired a postage-stamp-sized balcony on which we could murder tomato plants. Actual yards were out of the question for anyone who hadn’t bought a house on the west end of town 30 years ago; by the time we moved to Vancouver in 2006 as a tenure-track assistant professor and a trailing-spouse adjunct, it was already clear that we would never own a lawn.

It had been a long time since I thought about lawns. I don’t mean in a grand philosophical sense, or the stoned contemplation of a single blade of grass. I mean thought about them at all. Before moving to Mississippi we had lived in Vancouver for 13 years, where we felt lucky to have a place to store our toothbrushes and maybe an extra pair of slacks; we really hit the jackpot when we acquired a postage-stamp-sized balcony on which we could murder tomato plants. Actual yards were out of the question for anyone who hadn’t bought a house on the west end of town 30 years ago; by the time we moved to Vancouver in 2006 as a tenure-track assistant professor and a trailing-spouse adjunct, it was already clear that we would never own a lawn.

Robert Dash. Flower Bud of the Arbequina Olive Tree (black olives).

Robert Dash. Flower Bud of the Arbequina Olive Tree (black olives). What is it to be twenty? Forty? Sixty? Eighty? These points that mark the four quarters of a life — fifths if you’re lucky, larger portions if you’re not.

What is it to be twenty? Forty? Sixty? Eighty? These points that mark the four quarters of a life — fifths if you’re lucky, larger portions if you’re not.  1. The public library is holding a book or DVD for me.

1. The public library is holding a book or DVD for me.