Matthew Sweet in 1843 Magazine:

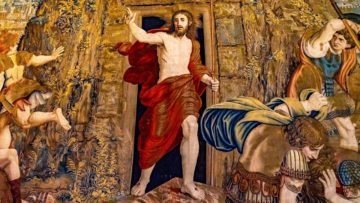

It’s not an age thing. Jesus was in his 30s when he rolled aside the stone from his tomb for Western culture’s foundational did-you-miss-me? moment. Gloria Swanson was 51 when she inhabited the forgotten body of silent-film star Norma Desmond and vogued down the staircase in “Sunset Boulevard”. That’s younger than Naomi Campbell is now. Why do some comebacks inspire and others appal? The best don’t erase the absence that made them possible or ignore its attendant trauma. When Elvis returned to live touring in 1968, audiences went wild for his exertions as much as his voice, and snatched the sweat-damp towels he tossed in their direction. When Monica Seles returned to tennis two years after a man had stabbed her with a nine-inch knife during a game, the crowd cheered her physical and mental victory over her attacker.

It’s not an age thing. Jesus was in his 30s when he rolled aside the stone from his tomb for Western culture’s foundational did-you-miss-me? moment. Gloria Swanson was 51 when she inhabited the forgotten body of silent-film star Norma Desmond and vogued down the staircase in “Sunset Boulevard”. That’s younger than Naomi Campbell is now. Why do some comebacks inspire and others appal? The best don’t erase the absence that made them possible or ignore its attendant trauma. When Elvis returned to live touring in 1968, audiences went wild for his exertions as much as his voice, and snatched the sweat-damp towels he tossed in their direction. When Monica Seles returned to tennis two years after a man had stabbed her with a nine-inch knife during a game, the crowd cheered her physical and mental victory over her attacker.

The Son of God fits this pattern too. Scourged, crucified, murdered, He returns in a shape fit for ascent to heaven. No more fieldwork, no more lecturing, no more miraculous catering, only the hereafter. And, we’re assured, it’s not just about Him. If we live the right kind of life, we get to do this too. When the band you loved as a teenager proves it can still fill a stadium, or an actor with whom you shared your youth comes back for a second act, it inspires and consoles. Comebacks suggest that the world is not, as some medieval scholars thought, a body in decay; that life isn’t a process of loss or dilution governed by the second law of thermodynamics. We look at the flowers rising in the parks and gardens, and think ourselves green again.

More here.

Hungarian-born

Hungarian-born  One would have to be a nihilist, of course, not to wish for an end to a pandemic that has claimed well over two and a half million lives. But for those of us interested in ‘interesting times’, and in the opportunities they open up, the global response to COVID-19 has not been without its political excitements. For the second time in twelve years governments around the world moved to underwrite a system that claims to need no government underwriting, with the result that many of the irrationalities of capitalism were thrown into relief. As incomes withered, or dried up completely, many people came to resent the extent to which their lives were governed by non-productive ownership – by rents and mortgages, principally, the profits from which are hoovered up by a parasitic property system and the financiers who sit atop it. At the same time, the invisible hand of the market was shown to be irrelevant to the needs of a society in crisis, while the speed with which the economy tanked, on the back of a dip in discretionary spending, revealed the basic absurdity of a system predicated on consumer choice.

One would have to be a nihilist, of course, not to wish for an end to a pandemic that has claimed well over two and a half million lives. But for those of us interested in ‘interesting times’, and in the opportunities they open up, the global response to COVID-19 has not been without its political excitements. For the second time in twelve years governments around the world moved to underwrite a system that claims to need no government underwriting, with the result that many of the irrationalities of capitalism were thrown into relief. As incomes withered, or dried up completely, many people came to resent the extent to which their lives were governed by non-productive ownership – by rents and mortgages, principally, the profits from which are hoovered up by a parasitic property system and the financiers who sit atop it. At the same time, the invisible hand of the market was shown to be irrelevant to the needs of a society in crisis, while the speed with which the economy tanked, on the back of a dip in discretionary spending, revealed the basic absurdity of a system predicated on consumer choice. Since 2010, I have been to Guantánamo 13 times. I can’t go as a scholar conducting research or a concerned citizen, so I go as a journalist. When I tell people that I am heading off to Guantánamo, responses tend to range from bafflement to curiosity. Highly educated and politically-aware acquaintances have said things like: “oh, I forgot that place was still open” and “what’s going on there these days?” The symbolic nadir of the US “war on terror” has faded in popular consciousness

Since 2010, I have been to Guantánamo 13 times. I can’t go as a scholar conducting research or a concerned citizen, so I go as a journalist. When I tell people that I am heading off to Guantánamo, responses tend to range from bafflement to curiosity. Highly educated and politically-aware acquaintances have said things like: “oh, I forgot that place was still open” and “what’s going on there these days?” The symbolic nadir of the US “war on terror” has faded in popular consciousness

Alex Hanna, Emily Denton, Razvan Amironesei, Andrew Smart, and Hilary Nicole in Logic:

Alex Hanna, Emily Denton, Razvan Amironesei, Andrew Smart, and Hilary Nicole in Logic: Marta Figlerowicz in Boston Review:

Marta Figlerowicz in Boston Review: McMurtry

McMurtry Forty years is a long time. I have to say that India is no longer the country of this novel. When I wrote Midnight’s Children I had in mind an arc of history moving from the hope – the bloodied hope, but still the hope – of independence to the betrayal of that hope in the so-called Emergency, followed by the birth of a new hope. India today, to someone of my mind, has entered an even darker phase than the Emergency years. The horrifying escalation of assaults on women, the increasingly authoritarian character of the state, the unjustifiable arrests of people who dare to stand against that authoritarianism, the religious fanaticism, the rewriting of history to fit the narrative of those who want to transform India into a Hindu-nationalist, majoritarian state, and the popularity of the regime in spite of it all, or, worse, perhaps because of it all – these things encourage a kind of despair.

Forty years is a long time. I have to say that India is no longer the country of this novel. When I wrote Midnight’s Children I had in mind an arc of history moving from the hope – the bloodied hope, but still the hope – of independence to the betrayal of that hope in the so-called Emergency, followed by the birth of a new hope. India today, to someone of my mind, has entered an even darker phase than the Emergency years. The horrifying escalation of assaults on women, the increasingly authoritarian character of the state, the unjustifiable arrests of people who dare to stand against that authoritarianism, the religious fanaticism, the rewriting of history to fit the narrative of those who want to transform India into a Hindu-nationalist, majoritarian state, and the popularity of the regime in spite of it all, or, worse, perhaps because of it all – these things encourage a kind of despair. Carl Zimmer’s book begins with a bang. Not a Big Bang, but a small one. In the fall of 1904, a 31-year-old physicist, John Butler Burke, working at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge University, made a “bouillon” of chunks of boiled beef in water. To this mix, he added a dab of radium, the newly discovered element glowing with radioactive energy, and waited overnight. The next morning, he skimmed the radioactive soup, smeared a layer on a glass slide and placed it under a microscope. He saw spicules of coalesced matter — “radiobes,” as he called them — that resembled, to his eyes, the most primeval forms of life.

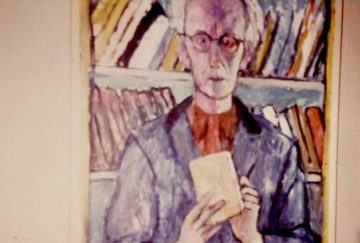

Carl Zimmer’s book begins with a bang. Not a Big Bang, but a small one. In the fall of 1904, a 31-year-old physicist, John Butler Burke, working at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge University, made a “bouillon” of chunks of boiled beef in water. To this mix, he added a dab of radium, the newly discovered element glowing with radioactive energy, and waited overnight. The next morning, he skimmed the radioactive soup, smeared a layer on a glass slide and placed it under a microscope. He saw spicules of coalesced matter — “radiobes,” as he called them — that resembled, to his eyes, the most primeval forms of life. The continuity stretching from the earlier flower and plant paintings to the landscape work in New Mexico comes from O’Keeffe’s lifelong obsession with looking at things. I mean that quite literally. How do you look at a thing? How do you see a thing? Well, you just look, don’t you? But O’Keeffe’s answer is, “No, you don’t just look, because you don’t know how to look.” So what’s the difference between looking in the normal way and looking in the O’Keeffe way? Much of it has to do with time. O’Keeffe liked to look at things for a long time. She’d stare at a single flower over and over again, hour after hour. We think we know what that means. But do we? I suspect the actual experience is crucial here. That’s to say, don’t assume you know what it means to look at one thing hour after hour unless you’ve done it. I’ve done it, sort of. I stared at a flower once more or less without interruption for over an hour. It was immensely difficult for the first twenty minutes or so. Then something changed. My vision started to surrender to something else. Everything suddenly slowed down and intensified. I started to see the flower as a whole, as well as the tiny individual parts, simultaneously. A kind of meditational state kicked in. My vision became a form, almost, of physical touching. It was sensuous and sensual, which is why all the critics who’ve talked about the sensuality of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings are not completely wrong.

The continuity stretching from the earlier flower and plant paintings to the landscape work in New Mexico comes from O’Keeffe’s lifelong obsession with looking at things. I mean that quite literally. How do you look at a thing? How do you see a thing? Well, you just look, don’t you? But O’Keeffe’s answer is, “No, you don’t just look, because you don’t know how to look.” So what’s the difference between looking in the normal way and looking in the O’Keeffe way? Much of it has to do with time. O’Keeffe liked to look at things for a long time. She’d stare at a single flower over and over again, hour after hour. We think we know what that means. But do we? I suspect the actual experience is crucial here. That’s to say, don’t assume you know what it means to look at one thing hour after hour unless you’ve done it. I’ve done it, sort of. I stared at a flower once more or less without interruption for over an hour. It was immensely difficult for the first twenty minutes or so. Then something changed. My vision started to surrender to something else. Everything suddenly slowed down and intensified. I started to see the flower as a whole, as well as the tiny individual parts, simultaneously. A kind of meditational state kicked in. My vision became a form, almost, of physical touching. It was sensuous and sensual, which is why all the critics who’ve talked about the sensuality of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings are not completely wrong. Artificial-intelligence systems are nowhere near advanced enough to replace humans in many tasks involving reasoning, real-world knowledge, and social interaction. They are showing human-level competence in low-level pattern recognition skills, but at the cognitive level they are merely imitating human intelligence, not engaging deeply and creatively, says

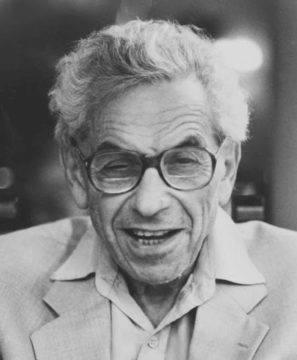

Artificial-intelligence systems are nowhere near advanced enough to replace humans in many tasks involving reasoning, real-world knowledge, and social interaction. They are showing human-level competence in low-level pattern recognition skills, but at the cognitive level they are merely imitating human intelligence, not engaging deeply and creatively, says  Somewhere out of the mysterious interplay between nature and nurture, internal and external factors, cultures and structures, and bottom-up and top-down forces there emerge the individual and group outcomes that we care about and which ultimately make the difference between human flourishing and its absence. What distinguishes various political ideologies, in effect, is how the line of causation is drawn, or, more specifically, from which direction. What gets left unexamined in the rush for compelling narratives and ideological certainty, however, is the territory between different causes and how they combine to shape reality. Few have gone further to map that territory than the American economist, political philosopher, and public intellectual Thomas Sowell.

Somewhere out of the mysterious interplay between nature and nurture, internal and external factors, cultures and structures, and bottom-up and top-down forces there emerge the individual and group outcomes that we care about and which ultimately make the difference between human flourishing and its absence. What distinguishes various political ideologies, in effect, is how the line of causation is drawn, or, more specifically, from which direction. What gets left unexamined in the rush for compelling narratives and ideological certainty, however, is the territory between different causes and how they combine to shape reality. Few have gone further to map that territory than the American economist, political philosopher, and public intellectual Thomas Sowell.