B D McClay in The New Yorker:

Sophie Blind is dead. Her head was cut clean off her shoulders as she made a dash for a taxi and was hit by a car. She doesn’t seem to mind, though it is a little awkward. “I knew I was dead when I came,” she admits, “but I didn’t want to be the first to say it.” Besides, the event didn’t leave much of a mark: “in less than half an hour,” she informs us, “normal traffic was resumed.” Though death and decapitation seem like straightforward facts, Sophie is the heroine of a novel: “Divorcing,” by Susan Taubes. And in a novel both of these things, it turns out, can be meant in different ways.

Sophie Blind is dead. Her head was cut clean off her shoulders as she made a dash for a taxi and was hit by a car. She doesn’t seem to mind, though it is a little awkward. “I knew I was dead when I came,” she admits, “but I didn’t want to be the first to say it.” Besides, the event didn’t leave much of a mark: “in less than half an hour,” she informs us, “normal traffic was resumed.” Though death and decapitation seem like straightforward facts, Sophie is the heroine of a novel: “Divorcing,” by Susan Taubes. And in a novel both of these things, it turns out, can be meant in different ways.

“Divorcing” is the only published book by Taubes, who shortly after its release, in 1969, drowned herself “in a ski jacket and slacks,” as the East Hampton Star would report when her body was found. She was forty-one. She left behind letters, some of which have been published; some unpublished writing; some scattered academic articles; and a dissertation still sitting in Harvard’s archives. She is doomed, it would seem, to always appear in the shadow of her longer-lived, more prolific husband, Jacob Taubes, as interesting in her own right, no elaboration. Interesting—but not that interesting. After her death, as she’d say, normal traffic resumed.

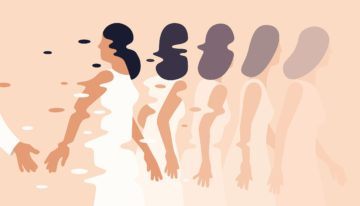

Susan Taubes and Sophie Blind share certain biographical traits: psychoanalyst fathers, intellectual husbands, needy mothers, Hungarian childhoods, a conflicted and sometimes even disdainful relationship with their own Jewishness. Nonetheless, “Divorcing,” which was recently reissued by New York Review Books, does not read like a roman à clef. It does engage, as many of those books do, with the collapse of a marriage and a subsequent search for meaning. But while the sort of novels dropped in its blurbs—Renata Adler’s “Speedboat” and Elizabeth Hardwick’s “Sleepless Nights”—occupy a cool, collected “I” that remains untouched, “Divorcing” is a much more unsettled affair. From its opening pages, which unspool in both first and third persons, from a heroine who may or may not have a head, the book does not even attempt stability. Sophie’s death is a case in point; Taubes has no interest in establishing whether it is metaphorical or literal. The book goes on to include dreams, letters, therapy sessions, and a widening study of Sophie’s family history. There are conversational fragments that could be taking place at almost any time within the narrative. And in the final pages, Sophie emerges from a nap and from a sensory deprivation chamber. Was all of the preceding a dream? Does it matter? Sophie Blind is dead. She isn’t here. She isn’t, at all.

More here.