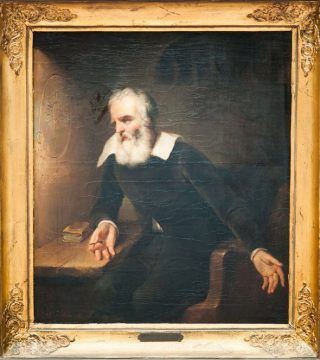

Mario Livio in Scientific American:

“And yet it moves.” This may be the most famous line attributed to the renowned scientist Galileo Galilei. The “it” in the quote refers to Earth. “It moves” was a startling denial of the notion, adopted by the Catholic Church at the time, that Earth was at the center of the universe and therefore stood still. Galileo was convinced that model was wrong. Although he could not prove it, his astronomical observations and his experiments in mechanics led him to conclude that Earth and the other planets were revolving around the sun. That brings us to “and yet.” As much as Galileo may have hoped to convince the Church that in moving Earth from its anointed position, he was not contradicting Scripture, he did not fully appreciate that Church officials could not accept what they regarded as his impudent invasion into their exclusive province: theology.

“And yet it moves.” This may be the most famous line attributed to the renowned scientist Galileo Galilei. The “it” in the quote refers to Earth. “It moves” was a startling denial of the notion, adopted by the Catholic Church at the time, that Earth was at the center of the universe and therefore stood still. Galileo was convinced that model was wrong. Although he could not prove it, his astronomical observations and his experiments in mechanics led him to conclude that Earth and the other planets were revolving around the sun. That brings us to “and yet.” As much as Galileo may have hoped to convince the Church that in moving Earth from its anointed position, he was not contradicting Scripture, he did not fully appreciate that Church officials could not accept what they regarded as his impudent invasion into their exclusive province: theology.

During his trial for suspicion of heresy, Galileo chose his words carefully. It was only after the trial, angered by his conviction no doubt, that he was said to have muttered to the inquisitors, “Eppur si muove”(“And yet it moves)”, as if to say that they may have won this battle, but in the end, truth would win out. But did Galileo really utter those famous words? There is no doubt that he thought along those lines. His bitterness about the trial; the fact that he had been forced to abjure and recant his life’s work; the humiliating reality that his book Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems had been put on the Church’s Index of Prohibited Books; and his deep contempt for the inquisitors who judged him continually occupied his mind for all the years following the trial. We can also be certain that he did not (as legend has it) mutter that phrase in front of the inquisitors. Doing so would have been insanely risky. But did he say it at all? If not, when and how did the myth about this motto start circulating?

More here.