Christian Wiman in Harper’s:

The second-worst thing about cancer chairs is that they are attached to televisions. Someone somewhere is always at war with silence. It’s impossible to read, so I answer email, or watch some cop drama on my computer, or, if it seems unavoidable, explore the lives of my nurses. A trip to Cozumel with old girlfriends, a costume party with political overtones, an advanced degree on the internet: they’re all the same, these lives, which is to say that the nurses tell me nothing, perhaps because amid the din and pain it’s impossible to say anything of substance, or perhaps because they know that nothing is precisely what we both expect. It’s the very currency of the place. Perhaps they are being excruciatingly candid.

The second-worst thing about cancer chairs is that they are attached to televisions. Someone somewhere is always at war with silence. It’s impossible to read, so I answer email, or watch some cop drama on my computer, or, if it seems unavoidable, explore the lives of my nurses. A trip to Cozumel with old girlfriends, a costume party with political overtones, an advanced degree on the internet: they’re all the same, these lives, which is to say that the nurses tell me nothing, perhaps because amid the din and pain it’s impossible to say anything of substance, or perhaps because they know that nothing is precisely what we both expect. It’s the very currency of the place. Perhaps they are being excruciatingly candid.

There is a cancer camaraderie I’ve never felt. That I find inimical, in fact. Along with the official optimism that percolates out of pamphlets, the milestone celebrations that seem aimed at children, the lemonade people squeeze out of their tumors. My stoniness has not always served me well. Among the cancer staff, there is special affection for the jocular sufferer, the one who makes light of lousy bowel movements and extols the spiritual tonic of neuropathy. And why not? Spend your waking life in hell, and you too might cherish the soul who’d learned to praise the flames. I can’t do it. I’m not chipper by nature, and just hearing the word cancer makes me feel like I’m wearing a welder’s mask.

In the cancer chair there is always a pillow and a blanket. I’ve never used either, though on two occasions (2007, 2013) my spastic reactions to my cure led nurses to hurriedly pile blankets on my feverish form in the way I pile blankets on my twin girls when they are cold. Now why did I have to think of that. The comparison, I mean. It is wildly inapt: the nurses’ ministrations are efficient and mirthless, and not once have they concluded with a good tickle. Why must the mind—my mind—make these errant excavations into pure pain? I was just digging along like a dog, chats and chairs, a pillow and a blanket.

My children have never seen a cancer chair. They’ve visited me during extended hospital stays, but that’s different, and the last one is just far back enough in their consciousnesses to be, for now, benign.

More here.

In 2005, Barry Marshall, an Australian gastroenterologist and researcher, shared the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery that peptic ulcers are caused not by stress, as was commonly thought, but by a bacterium called

In 2005, Barry Marshall, an Australian gastroenterologist and researcher, shared the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery that peptic ulcers are caused not by stress, as was commonly thought, but by a bacterium called  In his new book, The Drunken Silenus,

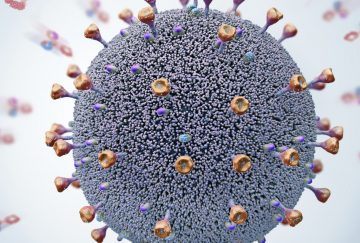

In his new book, The Drunken Silenus,  A pair of studies published this week is shedding light on the duration of immunity following COVID-19, showing patients lose their IgG antibodies—the virus-specific, slower-forming antibodies associated with long-term immunity—within weeks or months after recovery. With COVID-19, most people who become infected do

A pair of studies published this week is shedding light on the duration of immunity following COVID-19, showing patients lose their IgG antibodies—the virus-specific, slower-forming antibodies associated with long-term immunity—within weeks or months after recovery. With COVID-19, most people who become infected do  On Saturday, the

On Saturday, the In one of the twentieth century’s most memorable scenes from literature, a man is standing on a beach, pulling on a long rope that stretches out to sea. The rope is covered in thick seaweed. He yanks and tugs, and out of the foaming waves comes a horse’s head. It’s black and shiny and lies there at the water’s edge, its dead eyes staring while greenish eels slither from every orifice. The eels crawl out, shiny and entrails-like, more than two dozen of them; when the man has shoved them all into a potato sack, he pries open the horse’s grinning mouth, sticks his hands into its throat, and pulls out two more eels, as thick as his own arms.

In one of the twentieth century’s most memorable scenes from literature, a man is standing on a beach, pulling on a long rope that stretches out to sea. The rope is covered in thick seaweed. He yanks and tugs, and out of the foaming waves comes a horse’s head. It’s black and shiny and lies there at the water’s edge, its dead eyes staring while greenish eels slither from every orifice. The eels crawl out, shiny and entrails-like, more than two dozen of them; when the man has shoved them all into a potato sack, he pries open the horse’s grinning mouth, sticks his hands into its throat, and pulls out two more eels, as thick as his own arms. Until I read Howard Means’s Splash! and Bonnie Tsui’s Why We Swim, my main encounter with the history of the sport had been a Victorian-inspired swimming gala organised by members of my local team at north London’s Parliament Hill Lido. We competed in novelty races that predated the streamlining of swimming into a competitive sport, swimming upright holding umbrellas in one race, wearing blindfolds in another. We jumped into the pool in vintage dresses to see what it was like to swim hampered by heavy fabrics.

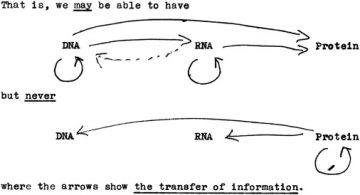

Until I read Howard Means’s Splash! and Bonnie Tsui’s Why We Swim, my main encounter with the history of the sport had been a Victorian-inspired swimming gala organised by members of my local team at north London’s Parliament Hill Lido. We competed in novelty races that predated the streamlining of swimming into a competitive sport, swimming upright holding umbrellas in one race, wearing blindfolds in another. We jumped into the pool in vintage dresses to see what it was like to swim hampered by heavy fabrics. Nothing—not even the Plague—has posed a more persistent threat to humanity than viral diseases: yellow fever, measles, and smallpox have been causing epidemics for thousands of years. At the end of the First World War, fifty million people died of the Spanish flu; smallpox may have killed half a billion during the twentieth century alone. Those viruses were highly infectious, yet their impact was limited by their ferocity: a virus may destroy an entire culture, but if we die it dies, too. As a result, not even smallpox possessed the evolutionary power to influence humans as a species—to alter our genetic structure. That would require an organism to insinuate itself into the critical cells we need in order to reproduce: our germ cells. Only retroviruses, which reverse the usual flow of genetic code from DNA to RNA, are capable of that. A retrovirus stores its genetic information in a single-stranded molecule of RNA, instead of the more common double-stranded DNA. When it infects a cell, the virus deploys a special enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, that enables it to copy itself and then paste its own genes into the new cell’s DNA. It then becomes part of that cell forever; when the cell divides, the virus goes with it. Scientists have long suspected that if a retrovirus happens to infect a human sperm cell or egg, which is rare, and if that embryo survives—which is rarer still—the retrovirus could take its place in the blueprint of our species, passed from mother to child, and from one generation to the next, much like a gene for eye color or asthma.

Nothing—not even the Plague—has posed a more persistent threat to humanity than viral diseases: yellow fever, measles, and smallpox have been causing epidemics for thousands of years. At the end of the First World War, fifty million people died of the Spanish flu; smallpox may have killed half a billion during the twentieth century alone. Those viruses were highly infectious, yet their impact was limited by their ferocity: a virus may destroy an entire culture, but if we die it dies, too. As a result, not even smallpox possessed the evolutionary power to influence humans as a species—to alter our genetic structure. That would require an organism to insinuate itself into the critical cells we need in order to reproduce: our germ cells. Only retroviruses, which reverse the usual flow of genetic code from DNA to RNA, are capable of that. A retrovirus stores its genetic information in a single-stranded molecule of RNA, instead of the more common double-stranded DNA. When it infects a cell, the virus deploys a special enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, that enables it to copy itself and then paste its own genes into the new cell’s DNA. It then becomes part of that cell forever; when the cell divides, the virus goes with it. Scientists have long suspected that if a retrovirus happens to infect a human sperm cell or egg, which is rare, and if that embryo survives—which is rarer still—the retrovirus could take its place in the blueprint of our species, passed from mother to child, and from one generation to the next, much like a gene for eye color or asthma. On May 13, 1961, two articles appeared in Nature, authored by a total of nine people, including Sydney Brenner, François Jacob and Jim Watson, announcing the isolation of messenger RNA (mRNA)

On May 13, 1961, two articles appeared in Nature, authored by a total of nine people, including Sydney Brenner, François Jacob and Jim Watson, announcing the isolation of messenger RNA (mRNA)  In Theory of the Gimmick (Harvard University Press, 2020), Ngai tracks the gimmick through a number of guises: stage props, wigs, stainless-steel banana slicers, temp agencies, fraudulent photographs, subprime loans, technological doodads, the novel of ideas. Across its many forms, the gimmick arouses our suspicion. When we say something is a gimmick, we mean it is overrated and deceptive, that you would have to be a sucker to fall for it. Yet gimmicks exert a strange hold on us. As with a magic show, we can enjoy the gimmick even while we know we are being tricked.

In Theory of the Gimmick (Harvard University Press, 2020), Ngai tracks the gimmick through a number of guises: stage props, wigs, stainless-steel banana slicers, temp agencies, fraudulent photographs, subprime loans, technological doodads, the novel of ideas. Across its many forms, the gimmick arouses our suspicion. When we say something is a gimmick, we mean it is overrated and deceptive, that you would have to be a sucker to fall for it. Yet gimmicks exert a strange hold on us. As with a magic show, we can enjoy the gimmick even while we know we are being tricked. Rome’s

Rome’s  A core principle of the academic movement that shot through elite schools in America since the early nineties was the view that individual rights, humanism, and the democratic process are all just stalking-horses for white supremacy. The concept, as articulated in books like former corporate consultant Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility (Amazon’s

A core principle of the academic movement that shot through elite schools in America since the early nineties was the view that individual rights, humanism, and the democratic process are all just stalking-horses for white supremacy. The concept, as articulated in books like former corporate consultant Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility (Amazon’s  O

O William James in turn experienced a vastation of his own. In Varieties of Religious Experience he provides a report by a ‘French correspondent’ – in reality, himself – that describes how on an ordinary evening, at twilight, ‘suddenly there fell upon me without warning, just as if it came out of darkness, a horrible fear of my own existence’. His terror became embodied in the image of an epileptic patient he had seen in an asylum, ‘like a sculptured Egyptian cat or Peruvian mummy, moving nothing but his black eyes … That shape am I.’

William James in turn experienced a vastation of his own. In Varieties of Religious Experience he provides a report by a ‘French correspondent’ – in reality, himself – that describes how on an ordinary evening, at twilight, ‘suddenly there fell upon me without warning, just as if it came out of darkness, a horrible fear of my own existence’. His terror became embodied in the image of an epileptic patient he had seen in an asylum, ‘like a sculptured Egyptian cat or Peruvian mummy, moving nothing but his black eyes … That shape am I.’ The millimeter-long roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans has about 20,000 genes—and so do you. Of course, only the human in this comparison is capable of creating either a circulatory system or a sonnet, a state of affairs that made this genetic equivalence one of the most confusing insights to come out of the Human Genome Project. But there are ways of accounting for some of our complexity beyond the level of genes, and as one new study shows, they may matter far more than people have assumed.

The millimeter-long roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans has about 20,000 genes—and so do you. Of course, only the human in this comparison is capable of creating either a circulatory system or a sonnet, a state of affairs that made this genetic equivalence one of the most confusing insights to come out of the Human Genome Project. But there are ways of accounting for some of our complexity beyond the level of genes, and as one new study shows, they may matter far more than people have assumed.