by Joan Harvey

Let’s face it, I’m tired. A phrase completely knotted up in the rather damaged circuitry that is my brain with Madeline Kahn in Blazing Saddles who managed to out-Dietrich Dietrich while being her own amazing self (if you haven’t watched this in at least the past few days you probably should). But, for better or worse, unlike Kahn, my tiredness is not from thousands of lovers coming and going and going and coming and always too soon.

But I digress. Tiredness is a digression from normal life. Repeated rounds of tiredness have been one of the leftovers people have reported experiencing from Covid-19, and, as I looked into it, from other viruses as well. I doubt I had Covid-19, but I did get very ill after flying back from NYC in late January and I’ve been struggling with recovery ever since. The tricky thing, the thing that really sucks, is that whereas with most bouts of tiredness one can recover relatively quickly and start normal physical activity, with this post-viral business, even tiny amounts of exercise can deplete one so much that only days of total rest really help. And, though I have past experience with this, I’m still not particularly well trained for it. The bigger problem, for me as well as others with this type of fatigue, is that one can feel fine during exercise, and then afterward become, as I have been, completely exhausted and shaky for days. As a pamphlet describing post-viral fatigue puts it, “Doing too much on a good day will often lead to an exacerbation of fatigue and any other symptoms the following day. This characteristic delay in symptom exacerbation is known as post-exertional malaise (PEM).” Read more »

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

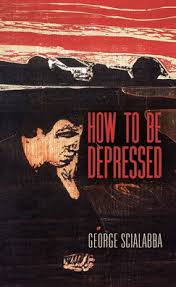

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose. Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

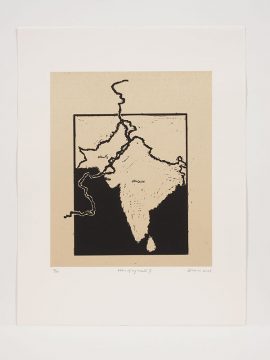

I was slightly nervous before my first meeting with the author Mirza Athar Baig, in the winter of 2017, at the Big M restaurant in Lahore’s Shadman Market. I had recently signed a book deal for my translation of his 2014 Urdu novel Hassan’s State of Affairs, and I was meeting him to discuss the first round of edits.

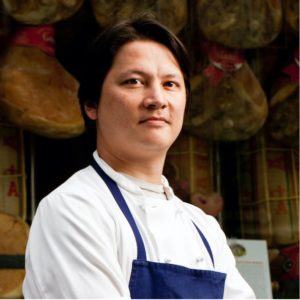

I was slightly nervous before my first meeting with the author Mirza Athar Baig, in the winter of 2017, at the Big M restaurant in Lahore’s Shadman Market. I had recently signed a book deal for my translation of his 2014 Urdu novel Hassan’s State of Affairs, and I was meeting him to discuss the first round of edits. Cooking is art, but it’s also very much science — mostly chemistry, but with important contributions from physics and biology. (Almost like a well-balanced recipe…) And I can’t think of anyone better to talk to about the intersection of these fields than Kenji López-Alt: professional chef and restauranteur, MIT graduate, and author of The Food Lab. We discuss how modern scientific ideas can improve your cooking, and more importantly, how to bring a scientific approach to cooking anything at all. Then we also get into the cultural and personal resonance of food, and offer a few practical tips.

Cooking is art, but it’s also very much science — mostly chemistry, but with important contributions from physics and biology. (Almost like a well-balanced recipe…) And I can’t think of anyone better to talk to about the intersection of these fields than Kenji López-Alt: professional chef and restauranteur, MIT graduate, and author of The Food Lab. We discuss how modern scientific ideas can improve your cooking, and more importantly, how to bring a scientific approach to cooking anything at all. Then we also get into the cultural and personal resonance of food, and offer a few practical tips.

In a short video documentary produced by the Tate Modern in London, the artist talks about her exhibition, “Letters from Home,” which opened on 28 March 2013. Through personal letters, the exhibition illustrates an immigrant’s disconnection from his or her homeland. In the

In a short video documentary produced by the Tate Modern in London, the artist talks about her exhibition, “Letters from Home,” which opened on 28 March 2013. Through personal letters, the exhibition illustrates an immigrant’s disconnection from his or her homeland. In the  The real saga of the Statue of Liberty—the symbolic face of America around the world, and the backdrop of New York’s dazzling Fourth of July fireworks show—is an obscure piece of U.S. history. It had nothing to do with immigration. The telltale clue is the chain under Lady Liberty’s feet: she is stomping on it. “In the early sketches, she was also holding chains in her hand,”

The real saga of the Statue of Liberty—the symbolic face of America around the world, and the backdrop of New York’s dazzling Fourth of July fireworks show—is an obscure piece of U.S. history. It had nothing to do with immigration. The telltale clue is the chain under Lady Liberty’s feet: she is stomping on it. “In the early sketches, she was also holding chains in her hand,”