Tim Wise in Counterpunch:

The moralizing has begun.

The moralizing has begun.

Those who have rarely been the target of organized police gangsterism are once again lecturing those who have about how best to respond to it. Be peaceful, they implore, as protesters rise up in Minneapolis and across the country in response to the killing of George Floyd. This, coming from the same people who melted down when Colin Kaepernick took a knee — a decidedly peaceful type of protest. Because apparently, when white folks say, “protest peacefully,” we mean “stop protesting.”

Everything is fine, nothing to see here.

It is telling that much of white America sees fit to lecture black people about the evils of violence, even as we enjoy the national bounty over which we claim possession solely as a result of the same. I beg to remind you, George Washington was not a practitioner of passive resistance. Neither the early colonists nor the nation’s founders fit within the Gandhian tradition. There were no sit-ins at King George’s palace, no horseback freedom rides to affect change. There were just guns, lots and lots of guns. We are here because of blood, and mostly that of others. We are here because of our insatiable desire to take by force the land and labor of others. We are the last people on Earth with a right to ruminate upon the superior morality of peaceful protest. We have never believed in it and rarely practiced it. Instead, we have always taken what we desire, and when denied it, we have turned to means utterly genocidal to make it so.

…In short, most white Americans are like that friend you have, who never went to medical school, but went to Google this morning and now feels confident he or she is qualified to diagnose your every pain. As with your friend and the med school to which they never gained entry, most white folks never took classes on the history of racial domination and subordination, but are sure we know more about it than those who did. Indeed, we suspect we know more about the subject than those who, more than merely taking the class, actually lived the subject matter.

When white folks ask, “Why are they so angry, and why do some among them loot?” we betray no real interest in knowing the answers to those questions.

More here.

Epidemiological studies are now revealing that the number of individuals who carry and can pass on the infection, yet remain completely asymptomatic, is larger than originally thought. Scientists believe these people have contributed to the spread of the virus in care homes, and they are central in the debate regarding face mask policies, as health officials attempt to avoid new waves of infections while societies reopen.

Epidemiological studies are now revealing that the number of individuals who carry and can pass on the infection, yet remain completely asymptomatic, is larger than originally thought. Scientists believe these people have contributed to the spread of the virus in care homes, and they are central in the debate regarding face mask policies, as health officials attempt to avoid new waves of infections while societies reopen.

What’s your reaction when you see the term “double-entry book-keeping”? Do you associate it with cool, societal-changing innovations like the Internet, Google, social media, laptops, and smartphones? Probably not. Neither did I—until I was asked to write a brief article about the fifteenth century Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli, to go into the sale catalog for the upcoming (June) Christie’s auction of an original first edition of his famous book Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita (“Summary of arithmetic, geometry, proportions and proportionality”), published in 1494, which I referred to in

What’s your reaction when you see the term “double-entry book-keeping”? Do you associate it with cool, societal-changing innovations like the Internet, Google, social media, laptops, and smartphones? Probably not. Neither did I—until I was asked to write a brief article about the fifteenth century Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli, to go into the sale catalog for the upcoming (June) Christie’s auction of an original first edition of his famous book Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita (“Summary of arithmetic, geometry, proportions and proportionality”), published in 1494, which I referred to in  Each of us is different, in some way or another, from every other person. But some are more different than others — and the rest of the world never stops letting them know. Societies set up “norms” that define what constitute acceptable standards of behavior, appearance, and even belief. But there will always be those who find themselves, intentionally or not, in violation of those norms — people who we might label “weird.” Olga Khazan was weird in one particular way, growing up in a Russian immigrant family in the middle of Texas. Now as an established writer, she has been exploring what it means to be weird, and the senses in which that quality can both harm you and provide you with hidden advantages.

Each of us is different, in some way or another, from every other person. But some are more different than others — and the rest of the world never stops letting them know. Societies set up “norms” that define what constitute acceptable standards of behavior, appearance, and even belief. But there will always be those who find themselves, intentionally or not, in violation of those norms — people who we might label “weird.” Olga Khazan was weird in one particular way, growing up in a Russian immigrant family in the middle of Texas. Now as an established writer, she has been exploring what it means to be weird, and the senses in which that quality can both harm you and provide you with hidden advantages. Albert Memmi, the great Tunisian-born French Jewish intellectual,

Albert Memmi, the great Tunisian-born French Jewish intellectual,  The moralizing has begun.

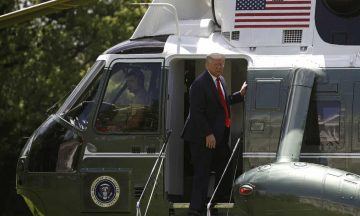

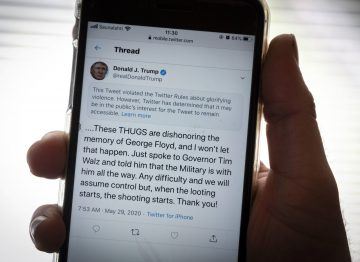

The moralizing has begun. You’d be forgiven if you hadn’t noticed. His verbal bombshells are louder than ever, but Donald J Trump is no longer president of the United States. By having no constructive response to any of the monumental crises now convulsing America, Trump has abdicated his office. He is not governing. He’s golfing, watching cable TV and tweeting. How has Trump responded to the widespread unrest following the murder in Minneapolis of George Floyd, a black man who died after a white police officer knelt on his neck for minutes as he was handcuffed on the ground? Trump called the protesters “thugs” and threatened to have them shot. “When the looting starts, the shooting starts,” he tweeted, parroting a former Miami police chief whose words spurred race riots in the late 1960s. On Saturday, he gloated about “the most vicious dogs, and most ominous weapons” awaiting protesters outside the White House, should they ever break through Secret Service lines.

You’d be forgiven if you hadn’t noticed. His verbal bombshells are louder than ever, but Donald J Trump is no longer president of the United States. By having no constructive response to any of the monumental crises now convulsing America, Trump has abdicated his office. He is not governing. He’s golfing, watching cable TV and tweeting. How has Trump responded to the widespread unrest following the murder in Minneapolis of George Floyd, a black man who died after a white police officer knelt on his neck for minutes as he was handcuffed on the ground? Trump called the protesters “thugs” and threatened to have them shot. “When the looting starts, the shooting starts,” he tweeted, parroting a former Miami police chief whose words spurred race riots in the late 1960s. On Saturday, he gloated about “the most vicious dogs, and most ominous weapons” awaiting protesters outside the White House, should they ever break through Secret Service lines. Peter E. Gordon and Sam Moyn debate if and how the “fascism” label is appropriate for Orbán, Erdoğan, Modi, or Trump, over at the NY Review of Books.

Peter E. Gordon and Sam Moyn debate if and how the “fascism” label is appropriate for Orbán, Erdoğan, Modi, or Trump, over at the NY Review of Books.  Stephen Nash in Sapiens:

Stephen Nash in Sapiens: O

O

Christian Barry and Seth Lazar in Ethics and International Affairs:

Christian Barry and Seth Lazar in Ethics and International Affairs: To untangle the Omegaverse fight, it helps to understand its origins in a parallel literary universe — the vast, unruly, diverse, exuberant and often pornographic world of fan fiction.

To untangle the Omegaverse fight, it helps to understand its origins in a parallel literary universe — the vast, unruly, diverse, exuberant and often pornographic world of fan fiction. Physicist Richard Feynman had the following advice for those interested in science: “So I hope you can accept Nature as She is—absurd.”

Physicist Richard Feynman had the following advice for those interested in science: “So I hope you can accept Nature as She is—absurd.” President Trump told reporters Friday evening that he didn’t know the racially charged history behind the phrase “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Trump tweeted the phrase Friday morning in reference to the

President Trump told reporters Friday evening that he didn’t know the racially charged history behind the phrase “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Trump tweeted the phrase Friday morning in reference to the