Nicolas Pelham in MIL:

Like many students of the Middle East, I am still haunted by Edward Said 41 years after he wrote “Orientalism”. The seminal book argued that Western academics, writers, artists and journalists had been agents of European soft power for over two centuries, constructing an image of the East that was exotic and therefore in need of taming. Orientalists’ art, literature, maps and artefacts reinforced the superior mindset of colonialists and whetted the appetite of Western governments to invade and possess Eastern nations, according to Said. His ideas shook up coverage of the Middle East years before I began working as a journalist in the region, but I wrote racked with guilt. On one of my first assignments in Egypt, the British embassy in Cairo flew me with the then British prime minister, John Major, to visit the war cemeteries that Britain tends for soldiers killed fighting in the deserts of El Alamein during the second world war. It was a privilege rarely afforded to a young reporter and they expected a puff piece. I returned with a report about irate locals demanding Britain give up control of a site commemorating battles between two invading European armies on Egyptian soil. I titled it “Egypt for the Egyptians”.

Like many students of the Middle East, I am still haunted by Edward Said 41 years after he wrote “Orientalism”. The seminal book argued that Western academics, writers, artists and journalists had been agents of European soft power for over two centuries, constructing an image of the East that was exotic and therefore in need of taming. Orientalists’ art, literature, maps and artefacts reinforced the superior mindset of colonialists and whetted the appetite of Western governments to invade and possess Eastern nations, according to Said. His ideas shook up coverage of the Middle East years before I began working as a journalist in the region, but I wrote racked with guilt. On one of my first assignments in Egypt, the British embassy in Cairo flew me with the then British prime minister, John Major, to visit the war cemeteries that Britain tends for soldiers killed fighting in the deserts of El Alamein during the second world war. It was a privilege rarely afforded to a young reporter and they expected a puff piece. I returned with a report about irate locals demanding Britain give up control of a site commemorating battles between two invading European armies on Egyptian soil. I titled it “Egypt for the Egyptians”.

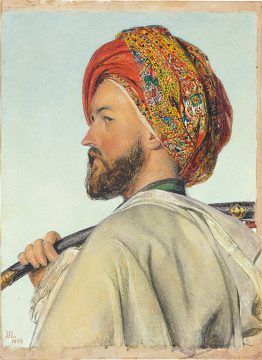

Since the publication of “Orientalism” in 1978 many museums and art galleries have hidden away their collections of desert landscapes, desolate ancient ruins and other memorabilia from 19th-century tours of the Orient. A new exhibition at the British Museum attempts to cast off the guilt and shame. Its neutral title – “Inspired by the East: how the Islamic world influenced Western art” – seems to strip art of political baggage. “We’re hoping to move beyond Said,” explains a curator. The exhibition hopes to highlight the quality of Orientalist art, presenting it as a more sincere – and surprising – cultural exchange.

The curators are right that Orientalism is more complex and blurred than Said believed.

More here.