Elif Batuman in The New York Times:

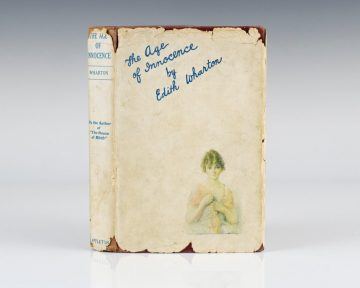

A literary “classic” is a recurring character in one’s life. One reads it, years go by, one reads it again, and it becomes the sum of those readings over time. One identifies with the character closest to one in age — and then one’s age changes. Eventually, each classic tells two stories: its own, and the story of all the times one has read it. In a way, in “The Age of Innocence,” Edith Wharton wrote an allegory of this very process: of the way stories acquire new meanings over time. Like most novels, “The Age of Innocence” offers a version of its author’s biography. Newland Archer, the central character, is, like Wharton herself, someone who has lived long enough to see the ideals of his youth become outdated.

A literary “classic” is a recurring character in one’s life. One reads it, years go by, one reads it again, and it becomes the sum of those readings over time. One identifies with the character closest to one in age — and then one’s age changes. Eventually, each classic tells two stories: its own, and the story of all the times one has read it. In a way, in “The Age of Innocence,” Edith Wharton wrote an allegory of this very process: of the way stories acquire new meanings over time. Like most novels, “The Age of Innocence” offers a version of its author’s biography. Newland Archer, the central character, is, like Wharton herself, someone who has lived long enough to see the ideals of his youth become outdated.

Edith Wharton was born in 1862, during the American Civil War. She started writing her first novel of manners at age 11, but her mother disapproved of women novelists, and of novels in general; she forbade Edith to read any more novels until after her marriage, which took place as soon as it could be arranged — in 1885, to a wealthy sportsman with manic-depressive tendencies. Wharton was 40 when she published her first novel, the year after her mother’s death. She wrote about one book per year for the rest of her life. In 1907, she moved to Paris, which is where she was at the start of World War I. People didn’t know yet that it was World War I, and called it the Great War. Many American expatriates left Paris at that time, but Wharton stayed behind, working on behalf of the hundreds of thousands of refugees who flooded across the French border. She personally housed 600 Belgian orphans, organized workshops for unemployed seamstresses and opened a home for tubercular children.

More here.