Emily Conover in Science News:

On a warm summer evening, a visitor to 1920s Göttingen, Germany, might have heard the hubbub of a party from an apartment on Friedländer Way. A glimpse through the window would reveal a gathering of scholars. The wine would be flowing and the air buzzing with conversations centered on mathematical problems of the day. The eavesdropper might eventually pick up a woman’s laugh cutting through the din: the hostess, Emmy Noether, a creative genius of mathematics.

On a warm summer evening, a visitor to 1920s Göttingen, Germany, might have heard the hubbub of a party from an apartment on Friedländer Way. A glimpse through the window would reveal a gathering of scholars. The wine would be flowing and the air buzzing with conversations centered on mathematical problems of the day. The eavesdropper might eventually pick up a woman’s laugh cutting through the din: the hostess, Emmy Noether, a creative genius of mathematics.

At a time when women were considered intellectually inferior to men, Noether (pronounced NUR-ter) won the admiration of her male colleagues. She resolved a nagging puzzle in Albert Einstein’s newfound theory of gravity, the general theory of relativity. And in the process, she proved a revolutionary mathematical theorem that changed the way physicists study the universe.

It’s been a century since the July 23, 1918, unveiling of Noether’s famous theorem. Yet its importance persists today. “That theorem has been a guiding star to 20th and 21st century physics,” says theoretical physicist Frank Wilczek of MIT.

Noether was a leading mathematician of her day. In addition to her theorem, now simply called “Noether’s theorem,” she kick-started an entire discipline of mathematics called abstract algebra.

More here.

I’ve of course been following the recent public debate about whether to build a circular collider to succeed the LHC—notably including

I’ve of course been following the recent public debate about whether to build a circular collider to succeed the LHC—notably including  I

I T

T

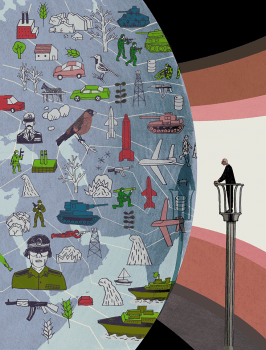

In recent weeks, Donald Trump’s pursuit of a border wall between the United States and Mexico has worked its way back in time — to the Middle Ages. Trump has happily agreed that his proposal is a distinctly “medieval solution.” “It worked then,” he declared in January, “and it works even better now.” That admission proved an invitation to critics, who inveighed against the wall as, in the words of the presidential hopeful Senator Kamala Harris, Trump’s “

In recent weeks, Donald Trump’s pursuit of a border wall between the United States and Mexico has worked its way back in time — to the Middle Ages. Trump has happily agreed that his proposal is a distinctly “medieval solution.” “It worked then,” he declared in January, “and it works even better now.” That admission proved an invitation to critics, who inveighed against the wall as, in the words of the presidential hopeful Senator Kamala Harris, Trump’s “ Mixed Korean: Our Stories, published by Truepeny Press, is an anthology featuring forty mixed Korean authors, and while not limited to Korean adoptees, adoptee voices feature prominently in the collection. In “Half Korean: My Story”, author Tanneke Beudeker writes about growing up half-Korean and half-African American in an adoptive Dutch family in the Netherlands, her childhood joy destroyed when white kids at her Christian school ostracize her for her race. “My parents tried to support me by talking to the teacher, and they did what most parents would do: they kept telling me sticks and stones may break by bones but words will never harm me. But they did, words broke my heart.” Though Beudeker eventually finds a meaningful career working with mentally challenged children, she still finds as an adult, “Even the slightest thing can trigger that old, familiar feeling of not being part of the herd.”

Mixed Korean: Our Stories, published by Truepeny Press, is an anthology featuring forty mixed Korean authors, and while not limited to Korean adoptees, adoptee voices feature prominently in the collection. In “Half Korean: My Story”, author Tanneke Beudeker writes about growing up half-Korean and half-African American in an adoptive Dutch family in the Netherlands, her childhood joy destroyed when white kids at her Christian school ostracize her for her race. “My parents tried to support me by talking to the teacher, and they did what most parents would do: they kept telling me sticks and stones may break by bones but words will never harm me. But they did, words broke my heart.” Though Beudeker eventually finds a meaningful career working with mentally challenged children, she still finds as an adult, “Even the slightest thing can trigger that old, familiar feeling of not being part of the herd.” The American Pragmatist Richard Rorty (1931-2007) advocated a therapeutic approach to philosophy throughout his career. He leaned quietly towards such an approach even in the early days, when his writings blended unobtrusively with a self-confident analytic tradition that certainly did not see any need for therapy. But it later became obvious in what is often regarded as his most important work: Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979).

The American Pragmatist Richard Rorty (1931-2007) advocated a therapeutic approach to philosophy throughout his career. He leaned quietly towards such an approach even in the early days, when his writings blended unobtrusively with a self-confident analytic tradition that certainly did not see any need for therapy. But it later became obvious in what is often regarded as his most important work: Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979). Is climate change more like an asteroid or diabetes? Last month, one of us

Is climate change more like an asteroid or diabetes? Last month, one of us  Ronald S. Sullivan Jr. is the faculty dean of Winthrop House, one of the 12 undergraduate dormitories in which most students live during their final three years at Harvard College. The faculty deans are mentors, guardians, and counselors — truly in loco parentis. They are responsible for their house’s overall social environment and manage a staff charged with facilitating the well-being of the students.

Ronald S. Sullivan Jr. is the faculty dean of Winthrop House, one of the 12 undergraduate dormitories in which most students live during their final three years at Harvard College. The faculty deans are mentors, guardians, and counselors — truly in loco parentis. They are responsible for their house’s overall social environment and manage a staff charged with facilitating the well-being of the students. And the title is not just a sonorous bit of rhetoric plucked from Shakespeare by producer Elliott Kastner, who needed something better than the “awful fucking title” MacLean had come up with (Castle of Eagles). Kastner’s title cleverly inverts or, as is said in the world of agents and double agents, “turns” the intended sense of the lines in Richard III: “The world is grown so bad / That wrens make prey where eagles dare not perch,” words that Burton could have enunciated with the clarity Larry Olivier would later bring to the voice-over of all twenty-six episodes of The World at War, starting with the famous opening shots of Oradour-sur-Glane (“Down this road, on a summer day in 1944, the soldiers came . . .”), a clarity Eastwood neither attempts nor envies, especially since the English officers in the briefing all look like they’re kitted out in uniforms from the previous war or a shelved episode of Dad’s Army while he lounges at the back in something much sharper, more contemporary, more American-looking, sporting a post-Elvis haircut and wearing the shoulder flashes, as Wymark points out, of the American Ranger Division.

And the title is not just a sonorous bit of rhetoric plucked from Shakespeare by producer Elliott Kastner, who needed something better than the “awful fucking title” MacLean had come up with (Castle of Eagles). Kastner’s title cleverly inverts or, as is said in the world of agents and double agents, “turns” the intended sense of the lines in Richard III: “The world is grown so bad / That wrens make prey where eagles dare not perch,” words that Burton could have enunciated with the clarity Larry Olivier would later bring to the voice-over of all twenty-six episodes of The World at War, starting with the famous opening shots of Oradour-sur-Glane (“Down this road, on a summer day in 1944, the soldiers came . . .”), a clarity Eastwood neither attempts nor envies, especially since the English officers in the briefing all look like they’re kitted out in uniforms from the previous war or a shelved episode of Dad’s Army while he lounges at the back in something much sharper, more contemporary, more American-looking, sporting a post-Elvis haircut and wearing the shoulder flashes, as Wymark points out, of the American Ranger Division. In 1942, the American composer Alan Hovhaness attended a master class at Tanglewood led by Bohuslav Martinů. In his early 30s at the time, Hovhaness had already written a considerable amount of music, including a symphony that the BBC Symphony Orchestra performed to some acclaim—the conductor of that concert, Leslie Heward, had proclaimed Hovhaness a “young genius.” Martinů’s class, however, was the province of Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, and other such hungry wolves. One day, a recording of Hovhaness’s symphony was played, eliciting a response that was derisive in the extreme. Copland could barely listen, chatting loudly throughout. Bernstein was even crueler: when the symphony concluded, he went to the piano, played a mocking minor scale, and declared, “I hate this dirty ghetto music.”

In 1942, the American composer Alan Hovhaness attended a master class at Tanglewood led by Bohuslav Martinů. In his early 30s at the time, Hovhaness had already written a considerable amount of music, including a symphony that the BBC Symphony Orchestra performed to some acclaim—the conductor of that concert, Leslie Heward, had proclaimed Hovhaness a “young genius.” Martinů’s class, however, was the province of Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, and other such hungry wolves. One day, a recording of Hovhaness’s symphony was played, eliciting a response that was derisive in the extreme. Copland could barely listen, chatting loudly throughout. Bernstein was even crueler: when the symphony concluded, he went to the piano, played a mocking minor scale, and declared, “I hate this dirty ghetto music.” Christine Korsgaard is a distinguished philosopher who has taught at Harvard for most of her career. Though not known to the general public, she is eminent within the field for her penetrating and analytically dense writings on ethical theory and her critical interpretations of the works of Immanuel Kant. Now, for the first time, she has written a book about a question that anyone can understand. Fellow Creatures: Our Obligations to the Other Animals is a blend of moral passion and rigorous theoretical argument. Though it is often difficult—not because of any lack of clarity in the writing but because of the intrinsic complexity of the issues—this book provides the opportunity for a wider audience to see how philosophical reflection can enrich the response to a problem that everyone should be concerned about.

Christine Korsgaard is a distinguished philosopher who has taught at Harvard for most of her career. Though not known to the general public, she is eminent within the field for her penetrating and analytically dense writings on ethical theory and her critical interpretations of the works of Immanuel Kant. Now, for the first time, she has written a book about a question that anyone can understand. Fellow Creatures: Our Obligations to the Other Animals is a blend of moral passion and rigorous theoretical argument. Though it is often difficult—not because of any lack of clarity in the writing but because of the intrinsic complexity of the issues—this book provides the opportunity for a wider audience to see how philosophical reflection can enrich the response to a problem that everyone should be concerned about. “Prof” was the English physicist and mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson, for whom doing science came as naturally as breathing. “It was just the way he looked at the world,” recalls his great-nephew, Lord Julian Hunt. “He was always questioning. Everything was an experiment.” Even at the age of 4, recounts his biographer Oliver Ashford in Prophet or Professor? Life and Work of Lewis Fry Richardson, the young Lewis had been prone to empiricism: Told that putting money in the bank would “make it grow,” he’d buried some coins in a bank of dirt. (Results: Negative.) In 1912, the now-grown Richardson had reacted to news of the Titanic’s sinking by setting out in a rowboat with a horn and an umbrella to test how ships might use directed blasts of noise to detect icebergs in fog. (Onlookers might have shaken their heads, but Richardson later won a patent for the fruit of that day’s work.) Nothing—not fellow scientists’ incomprehension, the distractions of teaching, or even an artillery bombardment—could dissuade him when, as he once put it, “a beautiful theory held me in its thrall.”

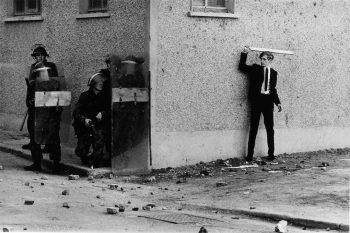

“Prof” was the English physicist and mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson, for whom doing science came as naturally as breathing. “It was just the way he looked at the world,” recalls his great-nephew, Lord Julian Hunt. “He was always questioning. Everything was an experiment.” Even at the age of 4, recounts his biographer Oliver Ashford in Prophet or Professor? Life and Work of Lewis Fry Richardson, the young Lewis had been prone to empiricism: Told that putting money in the bank would “make it grow,” he’d buried some coins in a bank of dirt. (Results: Negative.) In 1912, the now-grown Richardson had reacted to news of the Titanic’s sinking by setting out in a rowboat with a horn and an umbrella to test how ships might use directed blasts of noise to detect icebergs in fog. (Onlookers might have shaken their heads, but Richardson later won a patent for the fruit of that day’s work.) Nothing—not fellow scientists’ incomprehension, the distractions of teaching, or even an artillery bombardment—could dissuade him when, as he once put it, “a beautiful theory held me in its thrall.” The horrors of the battlefield are never far away in Tate Britain’s retrospective of Don McCullin’s work: the dead Khmer Rouge soldiers in a crater in Cambodia, Congolese soldiers tormenting freedom fighters in Stanleyville, young Christians on a bombed-out Beirut street, posing like a boy band over the body of a dead Palestinian girl. But McCullin has said again and again that he doesn’t like to be called a war photographer; preferring, simply, “photographer”. He is as interested in the people fighting wars as the people caught in their rip tide. “Starving Twenty Four Year Old Mother With Child” taken in Biafra in 1968, shows a woman, so gaunt she appears elderly, trying to feed her baby, who is sucking on empty, wrinkled breasts. Another picture, taken in a psychiatric hospital in Beirut in 1982, shows a child curled up on a mattress, flies settled on his body. He is tied to the metal bedstead with string, to stop him wandering off amid the broken glass. There is no need to see or hear the bombs to understand their effect on the helpless, and the desperation of those who care for them.

The horrors of the battlefield are never far away in Tate Britain’s retrospective of Don McCullin’s work: the dead Khmer Rouge soldiers in a crater in Cambodia, Congolese soldiers tormenting freedom fighters in Stanleyville, young Christians on a bombed-out Beirut street, posing like a boy band over the body of a dead Palestinian girl. But McCullin has said again and again that he doesn’t like to be called a war photographer; preferring, simply, “photographer”. He is as interested in the people fighting wars as the people caught in their rip tide. “Starving Twenty Four Year Old Mother With Child” taken in Biafra in 1968, shows a woman, so gaunt she appears elderly, trying to feed her baby, who is sucking on empty, wrinkled breasts. Another picture, taken in a psychiatric hospital in Beirut in 1982, shows a child curled up on a mattress, flies settled on his body. He is tied to the metal bedstead with string, to stop him wandering off amid the broken glass. There is no need to see or hear the bombs to understand their effect on the helpless, and the desperation of those who care for them. Anthropologists at the University of Oxford have discovered what they believe to be seven universal moral rules.

Anthropologists at the University of Oxford have discovered what they believe to be seven universal moral rules.