by Dave Maier

In the Third Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche levels a powerful attack on the modern Platonistic conception of mind and nature, urging us to reject such “contradictory concepts” as “knowledge in itself,” or the idea of “an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking.” More recently, Donald Davidson’s attack on the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content, and thus of belief and meaning, requires us to see inquiry into how things are as essentially interpretative.

In the Third Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche levels a powerful attack on the modern Platonistic conception of mind and nature, urging us to reject such “contradictory concepts” as “knowledge in itself,” or the idea of “an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking.” More recently, Donald Davidson’s attack on the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content, and thus of belief and meaning, requires us to see inquiry into how things are as essentially interpretative.

This idea can seem to conflict with our natural conception of the world as objective, fundamentally independent of what we say or think. In a similar context, Wittgenstein has his imaginary interlocutor challenge him (Philosophical Investigations §241): “So you are saying that human agreement decides what is true or false?” The implication is clear: if your position requires that what we say makes things true, rather than simply mirrors it, then that is an unacceptably irrealist result; how the world is cannot depend on what we say about it.

The suspicion can also arise – especially when the relevant reflections about language come from those steeped in literary theory – that “interpretivists” have mistakenly extrapolated from what may very well be true in the specific case of artistic interpretation and its objects to any discourse about the world at all. Similarly, defenders of the traditional view of objectivity such as John Searle (following John Austin here) have suggested that it is the specific cases of “illocutionary acts” such as “I hereby pronounce you man and wife,” which do indeed cause their objects to be thus truly described, that have unwittingly led to the interpretivist heresy. Read more »

Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text?

Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text?  Soon after I arrive in Chicago, on an August afternoon with a heat I remember from childhood, I head to a bar on the North Side and shoot pool. I haven’t been to this city in more than a year, because going home isn’t easy. But I’ve been called back for the wedding of a close friend, which will take place later in the weekend. My friend, the groom—let’s call him X.— is a journalist, and many of the other attendees are people like me, journalists or writers.

Soon after I arrive in Chicago, on an August afternoon with a heat I remember from childhood, I head to a bar on the North Side and shoot pool. I haven’t been to this city in more than a year, because going home isn’t easy. But I’ve been called back for the wedding of a close friend, which will take place later in the weekend. My friend, the groom—let’s call him X.— is a journalist, and many of the other attendees are people like me, journalists or writers. The tiny village of Lasserre is tucked into one of France’s southernmost hills, a hamlet of stone buildings strong in the embrace of centuries-old cement. The home in which the mathematician Alexander Grothendieck spent the last two decades of his life in near-complete seclusion is as tranquil as its neighbors. A patchwork of vines—trained, then abandoned—climb toward the white shutters and terracotta roof. Among the few postwar sentries is a standard-issue metal mailbox. Visitors left mostly unclaimed notes for him; letters via post were marked retour a l’envoyeur. The locals knew to leave him alone, but when a young mathematician arrived in the early 1990s in hopes of speaking to him, he slammed the door in her face, screaming.

The tiny village of Lasserre is tucked into one of France’s southernmost hills, a hamlet of stone buildings strong in the embrace of centuries-old cement. The home in which the mathematician Alexander Grothendieck spent the last two decades of his life in near-complete seclusion is as tranquil as its neighbors. A patchwork of vines—trained, then abandoned—climb toward the white shutters and terracotta roof. Among the few postwar sentries is a standard-issue metal mailbox. Visitors left mostly unclaimed notes for him; letters via post were marked retour a l’envoyeur. The locals knew to leave him alone, but when a young mathematician arrived in the early 1990s in hopes of speaking to him, he slammed the door in her face, screaming. The first Israeli mission to the moon carried a secret cargo, a small metal disk that contains the building blocks of human civilization in 30 million pages of information.

The first Israeli mission to the moon carried a secret cargo, a small metal disk that contains the building blocks of human civilization in 30 million pages of information. IF SOMEONE WERE TO MAKE

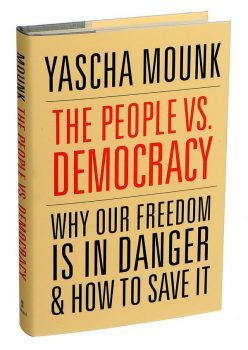

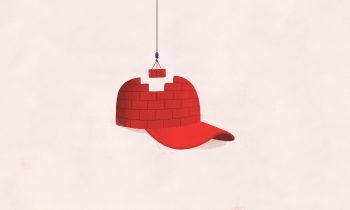

IF SOMEONE WERE TO MAKE There was once a liberal dream: “A free society of equals, based on the proliferation of opportunities for individuals to lead lives characterized by personal independence from the domination of others,” as Elizabeth Anderson writes of the Levellers during the English Civil War. In Yascha Mounk’s The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It, the liberal dream, limited as it might have been, has noticeably narrowed.

There was once a liberal dream: “A free society of equals, based on the proliferation of opportunities for individuals to lead lives characterized by personal independence from the domination of others,” as Elizabeth Anderson writes of the Levellers during the English Civil War. In Yascha Mounk’s The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It, the liberal dream, limited as it might have been, has noticeably narrowed. ‘The whole aim of practical politics,’ wrote H.L. Mencken, ‘is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary.’ Newspapers, politicians and pressure groups have been moving smoothly for decades from one forecast apocalypse to another (nuclear power, acid rain, the ozone layer, mad cow disease, nanotechnology, genetically modified crops, the millennium bug…) without waiting to be proved right or wrong.

‘The whole aim of practical politics,’ wrote H.L. Mencken, ‘is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary.’ Newspapers, politicians and pressure groups have been moving smoothly for decades from one forecast apocalypse to another (nuclear power, acid rain, the ozone layer, mad cow disease, nanotechnology, genetically modified crops, the millennium bug…) without waiting to be proved right or wrong. As irony would have it, Pakistan and India’s latest squabble began on Valentine’s Day when an explosive-laden truck, commandeered by a young Kashmiri Indian man, slammed into an

As irony would have it, Pakistan and India’s latest squabble began on Valentine’s Day when an explosive-laden truck, commandeered by a young Kashmiri Indian man, slammed into an  Advances in artificial intelligence have led many to speculate that human beings will soon be replaced by machines in every domain, including that of creativity. Ray Kurzweil, a futurist, predicts that by 2029 we will have produced an AI that can pass for an average educated human being. Nick Bostrom, an Oxford philosopher, is more circumspect. He does not give a date but suggests that philosophers and mathematicians defer work on fundamental questions to “superintelligent” successors, which he defines as having “intellect that greatly exceeds the cognitive performance of humans in virtually all domains of interest.”

Advances in artificial intelligence have led many to speculate that human beings will soon be replaced by machines in every domain, including that of creativity. Ray Kurzweil, a futurist, predicts that by 2029 we will have produced an AI that can pass for an average educated human being. Nick Bostrom, an Oxford philosopher, is more circumspect. He does not give a date but suggests that philosophers and mathematicians defer work on fundamental questions to “superintelligent” successors, which he defines as having “intellect that greatly exceeds the cognitive performance of humans in virtually all domains of interest.” For thousands of years, the liberal arts were not liberal, and that is why they are increasingly unwelcome in our time. An honest study of the past is unsettling in a liberal age, because a person who learns to venerate earlier cultural traditions, from Homer to the baroque, may come to venerate the values to which those traditions are devoted. And those values are a direct rebuke to the substance of liberalism.

For thousands of years, the liberal arts were not liberal, and that is why they are increasingly unwelcome in our time. An honest study of the past is unsettling in a liberal age, because a person who learns to venerate earlier cultural traditions, from Homer to the baroque, may come to venerate the values to which those traditions are devoted. And those values are a direct rebuke to the substance of liberalism. SKOOTER MCCOY WAS

SKOOTER MCCOY WAS  Look, we already know that Ishmael Reed hasn’t seen Hamilton.

Look, we already know that Ishmael Reed hasn’t seen Hamilton. “I love that,” said Thompson. “He’s for America 100%. It’s America or no way. I love that.” Thompson is an African American man in his early 20s. He was wearing a camouflage shirt under black overalls, with a large pin on his chest depicting a cartoon boy – a mashup of Calvin from Calvin and Hobbes and Trump himself – urinating on the CNN logo. People continued to walk past us en route to the rally. Mothers and daughters in University of Texas-El Paso sweatshirts. A man wearing an Uncle Sam costume. Groups of young men and groups of young women, and couples holding hands and dressed up as if the rally were a night on the town. A middle-aged blond woman rushed by in a head-to‑toe suede outfit, fringes flying as she crossed the street, the lights of the Coliseum beckoning.

“I love that,” said Thompson. “He’s for America 100%. It’s America or no way. I love that.” Thompson is an African American man in his early 20s. He was wearing a camouflage shirt under black overalls, with a large pin on his chest depicting a cartoon boy – a mashup of Calvin from Calvin and Hobbes and Trump himself – urinating on the CNN logo. People continued to walk past us en route to the rally. Mothers and daughters in University of Texas-El Paso sweatshirts. A man wearing an Uncle Sam costume. Groups of young men and groups of young women, and couples holding hands and dressed up as if the rally were a night on the town. A middle-aged blond woman rushed by in a head-to‑toe suede outfit, fringes flying as she crossed the street, the lights of the Coliseum beckoning.