by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

At the fourth Republican Presidential Debate, Senator Marco Rubio asserted that the country “needs more welders and less philosophers.” The small corner of the internet where professional philosophers reside promptly was awash with repudiation, criticism, and outrage (for example, here and here). We were, we have to admit, puzzled by it all – both by Rubio's statement and by the philosophers' outrage.

At the fourth Republican Presidential Debate, Senator Marco Rubio asserted that the country “needs more welders and less philosophers.” The small corner of the internet where professional philosophers reside promptly was awash with repudiation, criticism, and outrage (for example, here and here). We were, we have to admit, puzzled by it all – both by Rubio's statement and by the philosophers' outrage.

Senator Rubio's remarks were patently silly. First, the rationale Rubio offered, that “welders make more money than philosophers” is false. Moreover, the proposed reason, even were it true, is irrelevant – the social value of a profession is not a matter of the income paid to those who practice it. Surely no one would argue that hedge fund managers and reality TV stars are more socially valuable than nurses and carpenters simply on the basis of the difference between their respective paychecks. Finally, Rubio's reasoning is self-defeating, as there is no better way to decrease the earning power of a welder than by flooding the labor market with more competitors. For sure, Rubio's case was more rhetorical flourish than serious reasoning; he intended to draw a line in the sand between two perspectives on the role of education in society. His welders-versus-philosophers line was just window dressing for his view that education should aim to produce serviceable labor, not people who think.

Now, given these easy criticisms of Rubio's remarks, one might think that we were outraged by his claims. Many of our colleagues certainly were, and our inboxes and social media feeds quickly filled with missives of all shapes and sorts. But, we admit again, we found this phenomenon even more curious than Rubio's statement.

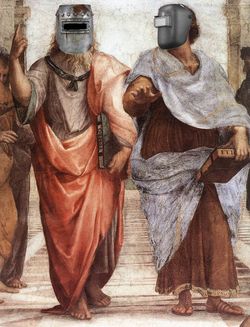

Here is why. There is nary a day that goes by without someone making a joke or remark to us about philosophy's alleged uselessness. Philosophy's oldest story highlights this. Thales of Miletus, who Aristotle counts as the first of the philosophers, apparently was walking one night and gazing up at the stars, contemplating their eternal motion. And then he fell in a well. A Thracian serving woman witnessed the fall, and laughed at him, urging that he should think about where he was putting his feet. Philosophy starts with a pratfall, and everyone, even those who have never taken a philosophy course or read any of the great books, gets the joke: It's not just that somebody fell in a well, it's that it was a philosopher.

Read more »

Here are some of my favorite surprising studies. What do they have in common?