by S. Abbas Raza

No matter how many books we read about how coincidences are to be expected in our lives simply due to the sheer amount of information we are bombarded with every day (and psychological reasons that certain kinds of things become salient to us because of various mental traits we share as humans), it still never fails to surprise us when they happen. This is not a scholarly essay but simply a report of one such coincidence that astonished me just yesterday.

No matter how many books we read about how coincidences are to be expected in our lives simply due to the sheer amount of information we are bombarded with every day (and psychological reasons that certain kinds of things become salient to us because of various mental traits we share as humans), it still never fails to surprise us when they happen. This is not a scholarly essay but simply a report of one such coincidence that astonished me just yesterday.

On Friday my wife and I went from the Südtirol to Genoa by train to spend the weekend with my sister who had traveled there from Boston to deliver a lecture at a medical conference. Before leaving home I threw a couple of books into my bag to read on the many trains we needed to take. We got there in the evening and ended up having a lovely weekend exploring Genoa and taking a boat to Portofino on Saturday to check out that lovely little town on the Italian Riviera. Yesterday afternoon, after a lunch of spicy doner kebabs, we got on a train from Genoa to Milan. We would then take a train from Milan to Verona, then another from there to Bolzano, and finally a short train ride on a fourth train to Brixen, where we live.

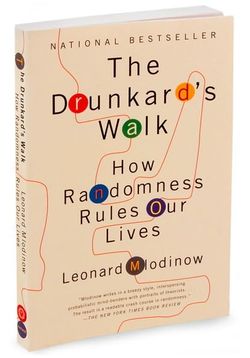

Anyway, so we got on the train to Milan and found seats. I took out my copy of Leonard Mlodinow's excellent book The Drunkard's Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives and started reading. At one point I was reading about a guy called Geralomo Cardano who wrote the first book ever on the theory of randomness in the mid-sixteenth century called The Book on Games of Chance. Leonard Mlodinow writes about him:

Anyway, so we got on the train to Milan and found seats. I took out my copy of Leonard Mlodinow's excellent book The Drunkard's Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives and started reading. At one point I was reading about a guy called Geralomo Cardano who wrote the first book ever on the theory of randomness in the mid-sixteenth century called The Book on Games of Chance. Leonard Mlodinow writes about him:

In the years leading up to 1576, an oddly attired old man could be found roving with a strange, irregular gait up and down the streets of Rome, shouting occasionally to no one in particular and being listened to by no one at all. He had once been celebrated throughout Europe, a famous astrologer, physician to nobles of the court, chair of medicine at the university of Pavia. (p. 41)

Reading this rather vivid description of the man I went into a sort of reverie imagining the distinguished but eccentric chair of medicine at the University of Pavia. For some reason, I imagined Pavia (which I really had never heard of before) to be close to Florence (my Italian geography is terrible) and I was imagining our man Cardano striding through streets laid down on rolling hills near the Arno river to make house calls on patients while carrying a doctor's bag full of potions and instruments. This made me think that perhaps I will visit Pavia next time I am in Florence and I thought also of looking it up on the internet when we got home. I was strangely gripped by a curiosity about what Pavia looks like.

I was jolted out of my extended daydream by the train having slowed down and finally jerking to a stop. We were at some small station in a small city about 20 minutes south of Milan. I stared at the scene outside and at the city beyond the station as the train started moving again. It was then that I saw the name on a large sign at the end of the platform as we passed by: yes, believe it or not, it was Pavia.

I exclaimed something incoherent out loud and told my wife what had happened while I tried to get my camera out and photograph the sign at the end of the platform but it was too late. It did give me a little shiver though. A little thrill. For a second it was almost as if Leonard Mlodinow and the world had conspired to teach me a small lesson about randomness even though, I know, I know well that they did not.

[The image at the top shows a somewhat impressionistic photo I shot a bit later out of the high-speed train window somewhere between Pavia and Milan.]