by Hasan Altaf

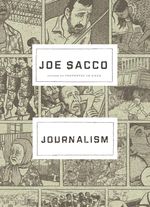

The title of Joe Sacco's Journalism (Metropolitan Books, 2012) ostensibly refers simply to the book's contents, the collection of the author's shorter reported pieces. Filed from the Hague, from Chechnya and Palestine, from Iraq, they have been published over the past few years in various magazines and newspapers, including Details, Harper's and the Times Magazine. It hints, though, at larger ambitions: Journalism is about not just the individual pieces, but also about journalism itself, as a practice and an art, a profession and maybe even a calling.

The title of Joe Sacco's Journalism (Metropolitan Books, 2012) ostensibly refers simply to the book's contents, the collection of the author's shorter reported pieces. Filed from the Hague, from Chechnya and Palestine, from Iraq, they have been published over the past few years in various magazines and newspapers, including Details, Harper's and the Times Magazine. It hints, though, at larger ambitions: Journalism is about not just the individual pieces, but also about journalism itself, as a practice and an art, a profession and maybe even a calling.

As one of the foremost practitioners of comics journalism, especially focused on conflict (he is most famous for his reporting from Bosnia and from Palestine), Sacco has the unique perspective of one who has had to face down the entrenched traditions and prejudices of his profession. In this volume's “introductory fusillade,” a self-described manifesto, he takes on some of the myths and sacred cows of the field. In particular, he addresses the challenge of objectivity, writing that “…there is nothing literal about a drawing. A cartoonist assembles elements deliberately and places them with intent on a page.” The cartoonist, that is, chooses everything, is responsible for everything; if the reporting involves a “river,” a writer can simply say “river” and a photographer can simply take a picture, but the cartoonist must choose precisely how he or she wants to depict that river.

In all forms of journalism, of course, objective reality is subjectively interpreted: Photographers choose what to shoot and how to shoot it; writers can flip an entire story on its head by shading their adjectives. It's easy to forget this, though; it's easier to read a reported piece as objective truth than to try to remain aware of all the assumptions behind that objectivity. As Sacco says, “journalists are not flies on the wall”: The presence of a journalist changes the story automatically, and the particular character and background and attitudes of that reporter change it further. Comics journalism of this kind – it's self-conscious, deliberately; Sacco usually draws himself within his stories, interacting with his sources or as another actor in the scene – serves to highlight that fact, making it clear just how much the reporter is in charge of our understanding.

Read more »