After I’d sat myself down at my computer on Tuesday morning, and after I’d checked in at my blog, New Savanna, and at Facebook, I zoomed here to 3QD, as I often do, and saw a link to an article about a Robert Frost poem. I, being an American citizen in good standing, know a bit about Frost. He’s sort of the Walt Disney of American poetry, him and Carl Sandburg, but apparently Frost had a nasty side as well. He’s not our nation’s kindly uncle. But then who knows what really goes on in the minds of those kindly uncles, eh?

This post had an intriguing title: “The Most Misread Poem in America”. Really? I gotta’ check that out. So I read the posted snippet, which was about “The Road Not Taken” – I’ve read that one, I think, said I to myself, but it’s not the one about miles to do until we eat? pray? love? one of those basic things – and then followed the link the full article, which is in the Paris Review. It’s by David Orr, poetry columnist for the New York Times Book Review, and is an excerpt from a book he’s devoted to that one poem.

It'll take a pretty determined individualist to take this road that's not been travelled in a looong time.

The common understanding, Orr tells us, is that the poem is about staunch individualism. Everyone else hightailed it down the popular road but me, individualist that I am, I took the less popular road, and it turned out darn well. That just won’t wash, not when you actually read the words carefully.

According to this reading, then, the speaker will be claiming “ages and ages hence” that his decision made “all the difference” only because this is the kind of claim we make when we want to comfort or blame ourselves by assuming that our current position is the product of our own choices (as opposed to what was chosen for us or allotted to us by chance). The poem isn’t a salute to can-do individualism; it’s a commentary on the self-deception we practice when constructing the story of our own lives. “The Road Not Taken” may be, as the critic Frank Lentricchia memorably put it, “the best example in all of American poetry of a wolf in sheep’s clothing.” But we could go further: It may be the best example in all of American culture of a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

I’ll buy that. But what if there’s something going on in the poem that isn’t adequately captured by limning its meaning?

About a decade after Frost published “The Road Not Taken” Archibald MacLeish told us “A poem should not mean / But be.” Is there a way to approach a poem’s being rather than its meaning?

I don’t really know. But I’m willing to take a look at the poem and see if I can come up with something that avoids the Scylla and Charybdis of pop individualism and professional knowingness. First, however, read the poem itself. If you know it well, you can skip over the words (though note that I’ve added line numbers to facilitate analysis). Otherwise, read it, slowly, perhaps even out loud.

The Poem

1 Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, 2 And sorry I could not travel both 3 And be one traveler, long I stood 4 And looked down one as far as I could 5 To where it bent in the undergrowth;

6 Then took the other, as just as fair, 7 And having perhaps the better claim, 8 Because it was grassy and wanted wear; 9 Though as for that the passing there 10 Had worn them really about the same,

11 And both that morning equally lay 12 In leaves no step had trodden black. 13 Oh, I kept the first for another day! 14 Yet knowing how way leads on to way, 15 I doubted if I should ever come back.

16 I shall be telling this with a sigh 17 Somewhere ages and ages hence: 18 Two roads diverged in a wood, and I— 19 I took the one less traveled by, 20 And that has made all the difference.

Poetical Mechanics

When I reread this poem, for the first time in decades, I was struck by two things: 1) that odd locution in lines 2 and 3, of being one traveler, and, especially, 2) line 16, “I shall be telling…” But let’s set those aside for a moment.

For I also had a sense that this might be a ring-form poem. What’s ring-form, or ring-composition? Imagine that you leave your place, walk a couple of blocks to the convenience store, purchase a quart of milk, and then return home by the same route. Along the way you take note of landmarks and, on returning, you notice them again. So:

1) Leave home 2) The old sycamore 3) Margie’s house 4) The place where the little yappy schnauzer lives 5) Store 4’) The place where the little yappy schnauzer lives 3’) Margie’s house 2’) The old sycamore 1’) Arrive Home

That kind of list is what’s meant by ring-form or ring-composition. It’s a verbal structure that’s symmetrical about a mid-point. In the small it’s a rhetorical figure called chiasmus. For example, there is the cliché, “you can take the boy out of the country, but you can’t take the country out of the boy.” There the symmetry is obvious as the figure spans such a short stretch of time. But such a scheme can be used to structure much longer stretches, such as President Obama’s eulogy from Clemente Pinckney, where the symmetry is not at all obvious [see my working paper].

At first glance “The Road Not Taken” doesn’t seem promising, as it consists of four stanzas of equal length. There’s no stanza to function as a middle unit (in effect, the convenience store).

However, lets look closely at lines 9-12:

9 Though as for that the passing there 10 Had worn them really about the same,

11 And both that morning equally lay 12 In leaves no step had trodden black.

Lines 11 and 12 say pretty much the same as 9 and 10, but with different words. Each pair asserts that those two divergent roads are pretty much the same. Lines 9 and 10 asserts they are worn about the same while 11 and 12 asserts that both were covered in leaves that hadn’t been stepped on. So, while these four lines stretch across two stanzas, let us nonetheless say that they form our midpoint. In effect, you enter the store in line 9, get the quart of milk in line 10, pay for it in 11, and exit the store in 12.

If they’re the mid-point, then we would expect some symmetry between what’s immediately before and immediately after. Lines 6-8 describe one of the roads (the second), while 13-15 are focused on the other one (the first). That satisfies the formal requirement of symmetry.

Now, is there a way in which the first and last stanzas stand in symmetrical apposition? Notice that line 18, in the middle of the last stanza, is almost the same as the poem’s opening line. Is that the symmetrical apposition we seek? I think it is, but in a way that’s a bit more interesting than mere repetition.

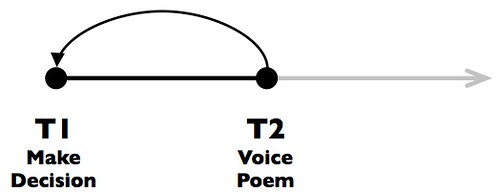

We’ve got to distinguish between the poet, or, more precisely, the poetic voice that utters/writes the poem, and the creature the poem is about, the fellow who’s there in the woods tromping around. Of course they are the same individual, but at different moments in time. Consider the following simple diagram, where we have time’s arrow from left, the past, toward the future, at the right:

At time one (T1) this person is walking in the woods, comes to a fork in the road, and has to decide which one to take. At T2 that same person has assumed the mantle of poet and is recalling that decision (the curved arrow pointing back to T1), while the as yet untrod future points off to the right.

So, at T2, in full poetic voice, he recounts the incident: “Two roads diverged […]”. And that flows through the first two stanzas and into the third, where it ends at line 12. If you look closely at the punctuation you’ll see that those twelve lines constitute a single sentence. That’s one unified mental act, set in the past.

The next line, 13, is a single sentence, thus a short one, but is punctuated as an exclamation. We’ve got a heightened emotional tone. But it’s still in the past: “I kept the first…” Now we finish the stanza with a two-line sentence, still in the past, but in a calmer mood. Just as the second sentence open with thoughts of the decision, so the third closes on thoughts of that decision.

So far we are dealing with the temporal situation depicted in our first diagram. The poet, in the present, tells about something that happened in the past. Now, what happens with the beginning of the last stanza?

“I shall be telling this…”–the tense has changed. The verb looks to the future. The question is: now where are we?

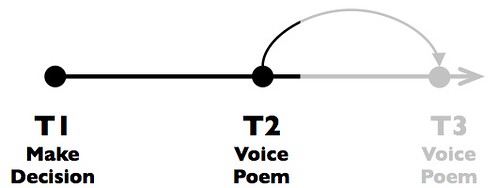

This diagram depicts what I will call the rational view:

The poet is still at T2 and is speaking of some future moment, “ages and ages hence”, long in the future, off there to the right. What happens in that future? Why: “Two roads diverged in a wood…”

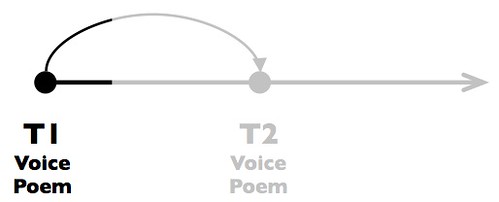

Let me offer an alternative, and more parsimonious view. Consider this diagram:

The speaking poet is now back at T1, thinking about the decision, and thinking of how, at some point in the future, which is now T2, he’ll tell the tale. And as soon as that poem, now time-travelled into the past, utters those words – “Two roads diverged” – the poem returns to the situation of that first diagram.

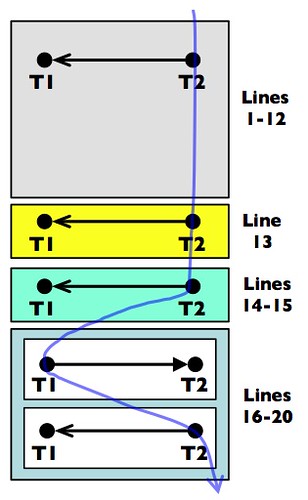

This, then, is what I think is going on:

Each of the poem’s four sentences is represented by a colored rectangle, with each rectangle labeled by the appropriate lines at the right. The blue line tracks the poetic voice from one sentence to the next. In the last stanza the voice slips into the past for the first two lines – making that past moment the present in which those lines are uttered – and then the voice slips forward for the last three lines of the poem.

As a list that shows the ring-composition:

1) “Two roads diverged” – ll. 1-5 2) road taken – ll. 6-8 Ω) roads are alike – ll. 9-12 2’) other road – ll. 13-15 1’) “Two roads diverged” – ll. 16-20

The explanation is a bit complex and long-winded, alas, but in practice its quite simple. Just follow the poem, concentrating on the words as they flow. If you do that, you’ll time travel.

Why not? It gets rid of that pesky T3 off there in the future, on the one hand, and there’s really nothing in the poem that prevents this “reading” – though it’s not so much a reading (interpretation) in the conventional sense as an assertion about how the verbal machinery is operating. Line 16 is in the future tense, and the repetition of the opening lines triggers a return to the original temporal situation.

The end of the poem has rejoined the beginning, like a snake swallowing its tail. Ring-form composition.

We’ve got one last problem. If that’s what’s going on, how did Frost get off this poetic merry-go-round? If each time he get’s to line 18, it sends him back to the beginning, how’d he ever manage to make it to line 19, which very obviously is there? Remember that movie, Ground Hog Day, where Bill Murray kept relieving the same day over and over until he finally got it right?

It would seem that Frost split himself in two, stuck a dash between them, and walked across that dash to the end of the poem. That dash I’m talking about is at the end of line 18 and so comes after the final word of that line, “I”, which is also the first word of line 19, “I”.

He’s NOT one traveler. He’s two. One keeps looping through that one moment ¬¬¬– a Wordsworthian spot in time? – while the other puts the pen down, ambles outside, and splits some logs for firewood.

But What About Meaning?

But what, you ask, of those two interpretations we started with, the (superficial) one about rugged individualism and the (more sophisticated) one about ad hoc rationalization of the past? They appear to have vanished, don’t they? Perhaps swallowed by the snake of time?

It’s not that I think both interpretations are wrong, mind you. It’s just that they are both interpretations. The poem itself is something different from its many and various interpretations. It is this marvelous bit of ecstatic mental apparatus that performs tricks with and for us. That’s why we like it.

As my friend (and expert on American poetry) Margaret Freeman suggested to me, quite often we don’t know just why a poem so pleases us. The inner mechanisms are hidden to us. There’s something going on, we keep reading and re-reading. And maybe we even go so far as to read about the poem – there’s a lot to read about this one. And maybe we even formulate our own interpretation. But the interpretation is just a rationalization. It doesn’t capture what the poem does to/through us. It doesn’t capture the poem’s being.

Nothing captures such being but the poems themselves. We can however, as Margaret indicated, attempt to examine and describe the cognitive and affective mechanisms that generate the being.

Understanding how a sprocket chain works won’t get you to the grocery store. Only riding the bicycle will do that. But if the bike breaks down, knowing something about sprocket chains might help you to fix it.

Can a deeper understanding the mechanisms of mind be of use in repairing injured spirits?

Another individualist heard from.

More About the Poem

The web site, Modern American Poetry, has excerpts from several discussions of “The Road Not Taken.” It would seem that the individualist reading has followed the poem almost from its publication in 1916. David Wyatt has a very interesting article about the poem, “Robert Frost and the Work of Retelling”, The Hopkins Review, Volume 8, Number 3, Summer 2015 (New Series), pp. 387-404. In particular, he notes that Frost had mentioned Wordsworth in his 1892 high-school valedictory address (p. 401).

Finally, I'd like to thank Margaret Freeman for reading a draft of this essay. I remain solely responsible for deficiencies.