Sleepless By Marie Darrieussecq

Samantha Harvey at The Guardian:

“All our body wants is to sleep, it wants to leave us, head back to the stable, a worn-out horse,” writes Marie Darrieussecq, at which I, a worn-out human, think yes. In a recent interview, Darrieussecq reflected on how much of her work is concerned with inhabiting. Who has a right to inhabit this planet, she asks, and who doesn’t? Though she was talking about her novel Crossed Lines, in which a Parisian woman finds her life becoming bound up with that of a young Nigerian refugee, she could just as well be referring to Sleepless (Pas Dormir in the original French), a book that is – what? A memoir/interrogation/painting/song of insomnia, her own and that of others. It’s a book about where, why, how we sleep and don’t sleep; about how to find a place in the world where sleep can happen, a stable for the worn-out horse.

“All our body wants is to sleep, it wants to leave us, head back to the stable, a worn-out horse,” writes Marie Darrieussecq, at which I, a worn-out human, think yes. In a recent interview, Darrieussecq reflected on how much of her work is concerned with inhabiting. Who has a right to inhabit this planet, she asks, and who doesn’t? Though she was talking about her novel Crossed Lines, in which a Parisian woman finds her life becoming bound up with that of a young Nigerian refugee, she could just as well be referring to Sleepless (Pas Dormir in the original French), a book that is – what? A memoir/interrogation/painting/song of insomnia, her own and that of others. It’s a book about where, why, how we sleep and don’t sleep; about how to find a place in the world where sleep can happen, a stable for the worn-out horse.

Sleepless isn’t a book that’s straightforward to convey, at least not briefly. On the page it’s fragmentary, footnoted and studded with photos and illustrations.

more here.

Cells And The Viruses That Feed On Them

Alex Johnson at the New York Times:

While recent events have provided a painful reminder of the very bad viruses that prey on us, Tom Ireland’s “The Good Virus” is a colorful redemption story for the oft-neglected yet incredibly abundant phage, and its potential for quelling the existential threat of antibiotic resistance, which scientists estimate might cause up to 10 million deaths per year by 2050. Ireland, an award-winning science journalist, approaches the subject of his first book with curiosity and passion, delivering a deft narrative that is rich and approachable.

While recent events have provided a painful reminder of the very bad viruses that prey on us, Tom Ireland’s “The Good Virus” is a colorful redemption story for the oft-neglected yet incredibly abundant phage, and its potential for quelling the existential threat of antibiotic resistance, which scientists estimate might cause up to 10 million deaths per year by 2050. Ireland, an award-winning science journalist, approaches the subject of his first book with curiosity and passion, delivering a deft narrative that is rich and approachable.

In the hands of d’Herelle and others, the phage became a potent tool in the fight against cholera. But, in the 1940s, when the discovery of the methods to produce penicillin at an industrial scale led to the “antibiotic era,” phage therapy came to be seen as quackery in Europe and America, in part, Ireland suggests, because antibiotics, unlike phages, fit the mold of capitalist society.

more here.

Saturday Poem

Heaney in an Irish Pub, Washington, DC

To reach the bar, he’s got to angle sideways—

the whooping clusters of bureaucrats and staffers

and aspiring pols don’t naturally give way,

nor do they part for him as, jostled and unnoticed

in his wilted raincoat, he ferries the Guinness back

to his table of literary riffraff and strays.

But the touring band, turning their jigs and reels,

know him by sight: as the squeeze box breathes,

the penny whistler’s fingers curl and splay,

their eyes return, through the blind crowd, to him.

Down from the stage at the break they shyly bend

to shake, to present in return, a gift, a tape.

Rare to see, here where art is kept

or held apart, how tenderly they know him

as one of theirs, a fine voice, true, trained on home,

and him asking them to sign their tape!

Later, resuming, they’re chuffed, grinning broadly.

How can the crowd know why, but joy leaks

from the band’s leavened tone and stance and touch

and up we rise—the whole room—on a tune.

by Sandy Solomon

from Plume Magazine

Friday, August 18, 2023

Place, Pastness, Poems: A Triptych

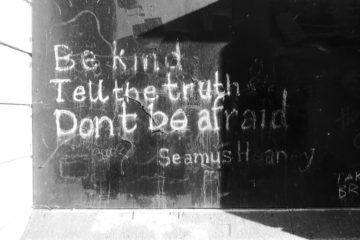

Seamus Heaney at Salmagundi:

It is well, at certain hours of the day and night, to look closely at the world of objects at rest. Wheels that have crossed long, dusty distances with their mineral and vegetable burdens, sacks from the coalbins, barrels and baskets, handles and hafts for the carpenter’s tool chest. From them flow the contacts of man with the earth … The used surfaces of things, the wear that the hands give to things, the air, tragic at times, pathetic at others, of such things—all lend a curious attractiveness to the reality of the world that should not be underprized.

It is well, at certain hours of the day and night, to look closely at the world of objects at rest. Wheels that have crossed long, dusty distances with their mineral and vegetable burdens, sacks from the coalbins, barrels and baskets, handles and hafts for the carpenter’s tool chest. From them flow the contacts of man with the earth … The used surfaces of things, the wear that the hands give to things, the air, tragic at times, pathetic at others, of such things—all lend a curious attractiveness to the reality of the world that should not be underprized.

Neruda’s declaration that “the reality of the world … should not be underprized” implies that we can and often do underprize it. We grow away from our primary relish of the phenomena. The rooms where we come to consciousness, the cupboards we open as toddlers, the shelves we climb up to, the boxes and albums we explore in reserved places in the house, the spots we discover for ourselves in those first solitudes out of doors, the haunts of those explorations at the verge of our security—in such places and at such moments “the reality of the world” first wakens in us.

more here.

Do Insects Feel Joy And Pain?

Lars Chittka at Scientific American:

The conventional wisdom about insects has been that they are automatons—unthinking, unfeeling creatures whose behavior is entirely hardwired. But in the 1990s researchers began making startling discoveries about insect minds. It’s not just the bees. Some species of wasps recognize their nest mates’ faces and acquire impressive social skills. For example, they can infer the fighting strengths of other wasps relative to their own just by watching other wasps fight among themselves. Ants rescue nest mates buried under rubble, digging away only over trapped (and thus invisible) body parts, inferring the body dimension from those parts that are visible above the surface. Flies immersed in virtual reality display attention and awareness of the passing of time. Locusts can visually estimate rung distances when walking on a ladder and then plan their step width accordingly (even when the target is hidden from sight after the movement is initiated).

Given the substantial work on the sophistication of insect cognition, it might seem surprising that it took scientists so long to ask whether, if some insects are that smart, perhaps they could also be sentient, capable of feeling.

more here.

Weight-loss meds like Ozempic may help curb addictive behaviors, but drugmakers aren’t running trials to find out

Meg Tirrell in CNN:

Cheri Ferguson has traded her vape pen for an Ozempic pen. One day seven weeks ago, “I thought, ‘you’re doing something about your weight; leave your vape at home,’ ” Ferguson said. She hasn’t picked it back up since, she says. Ferguson is one of many people taking Ozempic and similar drugs for weight loss who say they’ve also noticed an effect on their interest in addictive behaviors like smoking and alcohol. A smoker for most of her life, Ferguson started Ozempic 11 weeks ago to try to lose about 50 pounds she’d gained during the Covid-19 pandemic, which had made her prediabetic.

Cheri Ferguson has traded her vape pen for an Ozempic pen. One day seven weeks ago, “I thought, ‘you’re doing something about your weight; leave your vape at home,’ ” Ferguson said. She hasn’t picked it back up since, she says. Ferguson is one of many people taking Ozempic and similar drugs for weight loss who say they’ve also noticed an effect on their interest in addictive behaviors like smoking and alcohol. A smoker for most of her life, Ferguson started Ozempic 11 weeks ago to try to lose about 50 pounds she’d gained during the Covid-19 pandemic, which had made her prediabetic.

She’d switched from cigarettes to vaping last summer in hopes of quitting but found vapes to be even more addictive. That changed, she said, once she started Ozempic. “It’s like someone’s just come along and switched the light on, and you can see the room for what it is,” Ferguson said. “And all of these vapes and cigarettes that you’ve had over the years, they don’t look attractive anymore. It’s very, very strange. Very strange.” Ferguson said she drinks less alcohol on Ozempic, too. Whereas she would have had multiple drinks in a pub while watching a football match in Buckinghamshire, UK, she’s now content with just one. Some doctors say that when it comes to addictive behaviors, an effect on alcohol use is the most common thing they hear from people taking Ozempic or similar medicines.

More here.

Lydia Kiesling on Writing An Oil Novel In The Age of Climate Change

Jane Ciabattari at Literary Hub:

Lydia Kiesling’s first novel, The Golden State, begins with her stressed-out narrator Daphne grabbing her toddler from day care and taking off from her job at the Al-Ihsan Institute in Berkeley. She drives to the mobile home her late grandparents left her in Alta Vista in the high desert of Northern California, where she encounters a neighbor aligned with the radical right State of Jefferson movement and a sympathetic older woman who has spent time in Turkey. Meanwhile, Daphne’s husband is in immigrant limbo at his mother’s house in Istanbul after being tricked into giving up his green card. Based on this multi-textured and sparkling debut, Kiesling was a 2018 National Book Foundation “5 under 35” honoree.

Lydia Kiesling’s first novel, The Golden State, begins with her stressed-out narrator Daphne grabbing her toddler from day care and taking off from her job at the Al-Ihsan Institute in Berkeley. She drives to the mobile home her late grandparents left her in Alta Vista in the high desert of Northern California, where she encounters a neighbor aligned with the radical right State of Jefferson movement and a sympathetic older woman who has spent time in Turkey. Meanwhile, Daphne’s husband is in immigrant limbo at his mother’s house in Istanbul after being tricked into giving up his green card. Based on this multi-textured and sparkling debut, Kiesling was a 2018 National Book Foundation “5 under 35” honoree.

Kiesling’s new novel, Mobility, also tracks a single narrator on a journey. When we first meet Bunny Glenn she is a bored, boy-crazy fifteen year old “diplomat brat” living in Baku, on the oil-rich Caspian Sea, after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Her travels as she comes of age and becomes an aspirational worker in the oil industry carry her around the globe, ultimately back to Baku.

More here.

Friday Poem

Two Poems

Optimism

More and more I come to admire resilience.

Not the simple resistance of a pillow, whose foam

returns over and over to the same shape, but the sinuous

tenacity of a tree: finding the light newly blocked on one side,

it turns to another. A blind intelligence, true.

But out of such persistence arose turtles, rivers,

mitochondria, figs—all this resinous, intractable earth

Tree

It is foolish

to let a young redwood

grow next to a house.

Even in this

one lifetime,

you will have to choose.

The great calm being,

this clutter of soup pots and books—

Already the first branch-tips brush at the window.

Softly, calmly, immensity taps at your life.

by Jane Hirshfield

from Given Sugar, Given Salt

Harper Collins, 2001

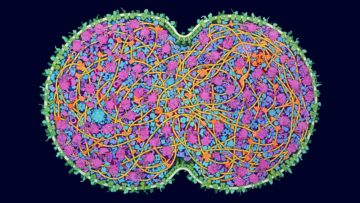

Even Synthetic Life Forms With a Tiny Genome Can Evolve

Yasemin Saplakoglu in Quanta:

Seven years ago, researchers showed that they could strip cells down to their barest fundamentals, creating a life form with the smallest genome that still allowed it to grow and divide in the lab. But in shedding half its genetic load, that “minimal” cell also lost some of the hardiness and adaptability that natural life evolved over billions of years. That left biologists wondering whether the reduction might have been a one-way trip: In pruning the cells down to their bare essentials, had they left the cells incapable of evolving because they could not survive a change in even one more gene?

Seven years ago, researchers showed that they could strip cells down to their barest fundamentals, creating a life form with the smallest genome that still allowed it to grow and divide in the lab. But in shedding half its genetic load, that “minimal” cell also lost some of the hardiness and adaptability that natural life evolved over billions of years. That left biologists wondering whether the reduction might have been a one-way trip: In pruning the cells down to their bare essentials, had they left the cells incapable of evolving because they could not survive a change in even one more gene?

Now we have proof that even one of the weakest, simplest self-replicating organisms on the planet can adapt. During just 300 days of evolution in the lab, the generational equivalent of 40,000 human years, measly minimal cells regained all the fitness they had sacrificed, a team at Indiana University recently reported in the journal Nature.

More here.

Leave men alone

Brendan O’Neill in Sp!ked:

Men, I have bad news: Caitlin Moran is coming for us. She comes not to man-bash, not to holler: ‘All men are rapists!’ It’s worse than that. She feels sorry for us. ‘I’m violently opposed to the branches of feminism that are permanently angry with men’, she writes at the very start of her very bad book. Instead she pities us. She frets over our toxic stoicism, our inability to be vulnerable, our unwillingness to be open about our fat bodies and small cocks. She wants to save us from all the ‘rules’ about ‘what a man should be’. From all that ‘swagger’ and ‘the stiff upper lip’. By the end I found myself pining for some good ol’ angry feminism.

Men, I have bad news: Caitlin Moran is coming for us. She comes not to man-bash, not to holler: ‘All men are rapists!’ It’s worse than that. She feels sorry for us. ‘I’m violently opposed to the branches of feminism that are permanently angry with men’, she writes at the very start of her very bad book. Instead she pities us. She frets over our toxic stoicism, our inability to be vulnerable, our unwillingness to be open about our fat bodies and small cocks. She wants to save us from all the ‘rules’ about ‘what a man should be’. From all that ‘swagger’ and ‘the stiff upper lip’. By the end I found myself pining for some good ol’ angry feminism.

What About Men? is, I’m going to be blunt, rubbish. I knew it would be from the very first page where Moran says that ‘when it comes to the vag-based problems, I have the bantz’. Imagine using the word bantz unironically in 2023. What she means is that she’s done all the vagina stuff. She’s completed feminism. She’s known as ‘the Woman Woman’, she says, in an arrogant timbre that puts to shame those cocksure blokes who stalk her nightmares. She wrote the bestselling pop-feminist tome, How To Be a Woman (2011), which contained such gems of wisdom as ‘don’t shave your vagina’ because it’s better to have a ‘big, hairy minge’, a ‘lovely furry moof’, ‘a marmoset sitting in [your] lap’, than a bald cooch. (Emmeline Pankhurst, I’m so sorry.) So now, naturally, she’s turning her attention to men. She’s discovered there is ‘a lot to say’ about ‘men in the 21st-century’. Lucky us.

More here.

Michael Sheen: The Magic of a Creative Career

Reducing inequality benefits everyone — so why isn’t it happening?

Editorial in Nature:

Last month, researchers from 67 nations wrote an open letter to United Nations secretary-general António Guterres and World Bank president Ajay Banga, urging them to “redouble efforts to address rising extreme inequality”. The move was motivated, in part, by the lack of progress on the 10th of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Nature is examining each goal in a series of editorials.

Last month, researchers from 67 nations wrote an open letter to United Nations secretary-general António Guterres and World Bank president Ajay Banga, urging them to “redouble efforts to address rising extreme inequality”. The move was motivated, in part, by the lack of progress on the 10th of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Nature is examining each goal in a series of editorials.

The aim of SDG 10 is to “reduce inequality within and among countries”. That means narrowing the difference between the incomes of the richest and the poorest, on both a national and an international level. The goal also proposes ensuring equality of opportunity. Unfortunately, the world is clearly failing to meet SDG 10. The letter’s authors go further, saying that the goal is being “largely ignored”.

More here.

Simone de Beauvoir | With Kathryn Sophia Belle, Skye Cleary, Lauren Elkin, and Kate Kirkpatrick

Thursday, August 17, 2023

Wednesday Poem

Intensive Sense

In the PICU . . .

I see bright lights,

But there is no sun,

And almost a loss of time.

I hear machines alarming,

Lives are not always saved.

I feel pain, intense at moments,

But I also feel the hurt of anxiety,

And neither anguish is good for the spirit.

Someday,

I will leave the PICU, again.

I will see the sun,

Rising into new days,

But I know it must set, too soon.

I will hear music sounding,

Ringing from so many instruments,

But most of it will be memories of my Heartsongs.

I will feel my spirit rejuvenated,

And I will be filled with hope again.

But, I will feel a sad sense of loss

For the children

Who will be Still

With the anguished sounding loss of time . . .

In the PICU.

by Mattie J.T. Stepanek

from Journey Through Heartsongs

VSP Books, 2001

PICU- Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

On Zadie Smith and the Gen X novel

Adam Kirsch in Harper’s Magazine:

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

In particular, Smith is interested in how the case challenges the views of her protagonist, Eliza Touchet. Eliza is a woman with the sharp judgment and keen perceptions of a novelist, though her era has deprived her of the opportunity to exercise those gifts. Her surname—pronounced in the French style, touché—evokes her taste for intellectual combat. But she has spent her life in a supportive role, serving variously as housekeeper and bedmate to her cousin William Harrison Ainsworth, a man of letters who churns out mediocre historical romances by the yard. (Like most of the novel’s characters, Ainsworth and Touchet are based on real-life historical figures.)

More here.

Sarah Sze’s Worlds of Wonder and Futility

Jackson Arn in The New Yorker:

Go to the Guggenheim Museum. Climb past the gift shops and walls of Gego and Picasso. Awaiting you on the top floor is the niftiest migraine you will ever experience. The artist responsible, Sarah Sze, has contributed a set of site-specific pieces that look like a single shantytown of projectors, plastic bottles, potted plants, paintings, photographs, papers, and pills, to name only a handful of the “P”s. There are thousands of other bits, many of them mass-produced tools doing any job but the one they were made for. Everything is stacked or fanned or strewn, and looks a sneeze away from collapse. Red clamps and blue tape take credit for the hard work done by secret dabs of glue, while other yips of color compete with the gray floors, and lose. Most of the installations are lit by the museum’s glow, and one isn’t lit at all, but for some reason I imagine the entire set in the prickly glare of a conference room.

Go to the Guggenheim Museum. Climb past the gift shops and walls of Gego and Picasso. Awaiting you on the top floor is the niftiest migraine you will ever experience. The artist responsible, Sarah Sze, has contributed a set of site-specific pieces that look like a single shantytown of projectors, plastic bottles, potted plants, paintings, photographs, papers, and pills, to name only a handful of the “P”s. There are thousands of other bits, many of them mass-produced tools doing any job but the one they were made for. Everything is stacked or fanned or strewn, and looks a sneeze away from collapse. Red clamps and blue tape take credit for the hard work done by secret dabs of glue, while other yips of color compete with the gray floors, and lose. Most of the installations are lit by the museum’s glow, and one isn’t lit at all, but for some reason I imagine the entire set in the prickly glare of a conference room.

Clutter is Sze’s medium. She can infuse it with any flavor and play it at any volume. Some of what happens in her work is accidental—“P” is also for “pedestal fans,” which blow through the exhibition, rustling threads and scraps—but even accident is just another one of her ingredients, measured out to the milligram. A team of assistants keeps things in a permanent state of fussy disarray, dropping by thrice a week to adjust threads, refill plastic bottles to make up for evaporation, and so on. The results are less a parody than a triumph of micromanagement: much of the fun in these installations comes from seeing how thin they can stretch, how many different things and ideas and tones they can keep going at once. Images from every land and clime hint at the absurdity of an interconnected planet, as well as the glory. A little circle of rocks, matches, and other stuff reminded me both of Stonehenge and the Stonehenge replica my fifth-grade class built out of blocks and paper-towel rolls.

More here.

2 Leading Theories of Consciousness Square Off

Carl Zimmer in the New York Times:

On a muggy June night in Greenwich Village, more than 800 neuroscientists, philosophers and curious members of the public packed into an auditorium. They came for the first results of an ambitious investigation into a profound question: What is consciousness?

On a muggy June night in Greenwich Village, more than 800 neuroscientists, philosophers and curious members of the public packed into an auditorium. They came for the first results of an ambitious investigation into a profound question: What is consciousness?

To kick things off, two friends — David Chalmers, a philosopher, and Christof Koch, a neuroscientist — took the stage to recall an old bet. In June 1998, they had gone to a conference in Bremen, Germany, and ended up talking late one night at a local bar about the nature of consciousness.

For years, Dr. Koch had collaborated with Francis Crick, a biologist who shared a Nobel Prize for uncovering the structure of DNA, on a quest for what they called the “neural correlate of consciousness.” They believed that every conscious experience we have — gazing at a painting, for example — is associated with the activity of certain neurons essential for the awareness that comes with it.

Dr. Chalmers liked the concept, but he was skeptical that they could find such a neural marker any time soon.

More here.

Exploring The Thoughts, Memories, And Personalities Of Bees

Leon Vlieger in The Inquisitive Biologist:

The collectives formed by social insects fascinate us, whether it is bees, ants, or termites. But it would be a mistake to think that the individuals making up such collectives are just mindless cogs in a bigger machine. It is entirely reasonable to ask, as pollination ecologist Stephen Buchmann does here, what a bee knows. This book was published almost a year after Lars Chittka’s The Mind of a Bee, which I reviewed previously. I ended that review by asking what Buchmann could add to the subject. Actually, despite some unavoidable overlap, a fair amount. Join me for the second of this two-part dive into the bee brain.

The collectives formed by social insects fascinate us, whether it is bees, ants, or termites. But it would be a mistake to think that the individuals making up such collectives are just mindless cogs in a bigger machine. It is entirely reasonable to ask, as pollination ecologist Stephen Buchmann does here, what a bee knows. This book was published almost a year after Lars Chittka’s The Mind of a Bee, which I reviewed previously. I ended that review by asking what Buchmann could add to the subject. Actually, despite some unavoidable overlap, a fair amount. Join me for the second of this two-part dive into the bee brain.

More here.

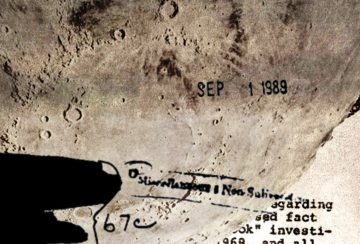

An America of Secrets

Jon Askonas in The New Atlantis:

There have been two dominant narratives about the rise of misinformation and conspiracy theories in American public life.

There have been two dominant narratives about the rise of misinformation and conspiracy theories in American public life.

What we can, without prejudice, call the establishment narrative — put forward by dominant foundations, government agencies, NGOs, the mainstream press, the RAND corporation — holds that the misinformation age was launched by the Internet boom, the loss of media gatekeepers, new alternative sources of sensational information that cater to niche audiences, and social media. According to this story, the Internet in general and social media in particular reward telling audiences what they want to hear and undermining faith in existing institutions. A range of nefarious actors, from unscrupulous partisan media to foreign intelligence agencies, all benefit from algorithms that are designed to boost engagement, which winds up catering misinformation to specific audience demands. Traditional journalism, bound by ethics, has not been able to keep up.

The alternative narrative — put forward by Fox News, the populist fringes of the Left and the Right, Substackers of all sorts — holds almost the inverse.

More here.