Daniel Mendelsohn in The New Yorker:

In August of 1929, Sigmund Freud scoffed at the notion that he would do anything as crass as write an autobiography. “That is of course quite an impossible suggestion,” he wrote to his nephew, who had conveyed an American publisher’s suggestion that the great man write his life story. “Outwardly,” Freud went on, perhaps a trifle disingenuously, “my life has passed calmly and uneventfully and can be covered by a few dates.” Inwardly—and who knew better?—things were a bit more complicated:

In August of 1929, Sigmund Freud scoffed at the notion that he would do anything as crass as write an autobiography. “That is of course quite an impossible suggestion,” he wrote to his nephew, who had conveyed an American publisher’s suggestion that the great man write his life story. “Outwardly,” Freud went on, perhaps a trifle disingenuously, “my life has passed calmly and uneventfully and can be covered by a few dates.” Inwardly—and who knew better?—things were a bit more complicated:

A psychologically complete and honest confession of life, on the other hand, would require so much indiscretion (on my part as well as on that of others) about family, friends, and enemies, most of them still alive, that it is simply out of the question. What makes all autobiographies worthless is, after all, their mendacity.

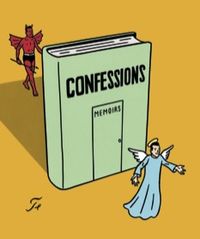

Freud ended by suggesting that the five-thousand-dollar advance that had been offered was a hundredth of the sum necessary to tempt him into such a foolhardy venture. Unseemly self-exposures, unpalatable betrayals, unavoidable mendacity, a soupçon of meretriciousness: memoir, for much of its modern history, has been the black sheep of the literary family. Like a drunken guest at a wedding, it is constantly mortifying its soberer relatives (philosophy, history, literary fiction)—spilling family secrets, embarrassing old friends—motivated, it would seem, by an overpowering need to be the center of attention. Even when the most distinguished writers and thinkers have turned to autobiography, they have found themselves accused of literary exhibitionism—when they can bring themselves to put on a show at all. When Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “Confessions” appeared, shocking the salons of eighteenth-century Paris with matter-of-fact descriptions of the author’s masturbation and masochism, Edmund Burke lamented the “new sort of glory” the eminent philosophe was getting “from bringing hardily to light the obscure and vulgar vices, which we know may sometimes be blended with eminent talents.” (The complaint sounds eerily familiar today.) When, at the suggestion of her sister, Virginia Woolf started, somewhat reluctantly, to compose an autobiographical “sketch,” she found herself, inexplicably at first, thinking of a certain hallway mirror—the scene, as further probing of her memory revealed, of an incestuous assault by her half-brother Gerald, an event that her memory had repressed, and about which, in the end, she was unable to write for publication.

In August of 1929, Sigmund Freud scoffed at the notion that he would do anything as crass as write an autobiography. “That is of course quite an impossible suggestion,” he wrote to his nephew, who had conveyed an American publisher’s suggestion that the great man write his life story. “Outwardly,” Freud went on, perhaps a trifle disingenuously, “my life has passed calmly and uneventfully and can be covered by a few dates.” Inwardly—and who knew better?—things were a bit more complicated: