by Steve Szilagyi

Having invisible friends is not necessarily a bad thing. What matters is how you handle it. You could, like the engineer Emmanuel Swedenborg or the poet William Blake, spin whole theologies out of your visions. Or you could try and ignore your invisible companions, like the philosopher Jean Paul Sartre, and hope they’ll go away (they won’t. Not for a while at least). Here we’ll see that the best thing to do is to learn to live with the darn things. That’s how Calvin Stowe, the husband of American author Harriet Beecher Stowe, handled his teeming world of invisible companions, setting an example of savoir faire from which we can all take heart.

For much of his young life, Calvin Stowe believed that the Bible sanctioned slavery. He was in a good position to know this, being among the most erudite biblical scholars of his day and able to read scripture in Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek and Latin. He knew every square inch of holy writ the way a bored student knows the top of his desk. And as far as he could see the Bible was okay with human bondage. Then, in 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, a law that required Northern citizens to help capture runaway slaves. Sickened by this mad injustice, Stowe flipped his beliefs, and where he once saw scripture justifying slavery, he now saw its opposite. In a letter to his wife, he wrote:

“Hattie, if I could use a pen as you can, I would write something that would make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.”

Harriet, then a modestly successful author, responded by writing the powerful anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin – which whipped up sentiments leading to the American Civil War, played a key role in the abolition of slavery and indirectly led to the deaths of some 600,000 people.

A total lack of imagination. The letter quoted above and the change of heart it reflects establish a certain context for understanding Calvin Stowe’s striking visions. For one thing, it shows that Calvin was a sensible person. Sane and willing to change his mind in the face of contrary evidence. Not a fanatic in any sense of the word. Second, it underscores what he always claimed was his total lack of imagination: “If I could use my pen …”

Writing as early as 1832, Stowe claimed to have neither the “taste nor talent for fiction or poetry” and “barely imagination enough” to enjoy those things. His own writings, he noted, were dry, plain and matter of fact. Yet despite this …

“As early as I can remember anything, I can remember observing a multitude of animated and active objects, which I could see with perfect distinctness … passing through the floors, and the ceilings, and the walls of the house. These appearances occasioned neither surprise nor alarm, except when they assumed some hideous and frightful form … for I became acquainted with them as soon as with any of the objects of sense.”

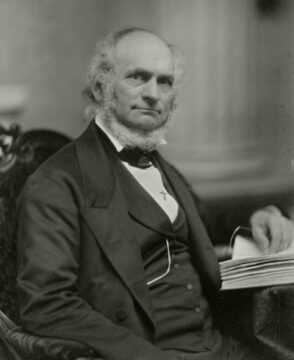

Calvin Stowe went about his respectable life accompanied by swarms of men, women, imps, fairies and devils visible only to himself. Sometimes he had interactions with them. Other times, they talked and tussled with one another without regard to his presence. In 1832, he wrote an almost naively frank description of his visions up to that point in his life, hoping that it might be of interest to the “psychologist” or “scientific physician”. (Calvin’s account appears in full in Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe, Compiled from her Letters and Journals, by her son, Charles Henry Stowe.)

Gambols of phantoms. With his customary precision, Stowe told how he was regularly visited by “a very large Indian woman and very small Indian man, with a huge bass viol between them,” upon which they occasionally played harsh notes while quarreling with one another. Stowe remembered the details of their clothing, from the woman’s “high, dark grey fur hat … lined with red” to the man’s “shabby, black-colored overcoat” and “tight-fitting hat”.

The ill-tempered couple emerged from a closet which was “a famous place for the gambols of phantoms” who swarmed the house and surrounding countryside. Lying in bed, Stowe liked to watch the chorus line of sprites who danced upon the windowsill. His phantoms took on the aspect of their environment, being “rude and rough” in an unfinished room, or more natural “when I saw them in the woods or in the meadows, upon the water or upon the ground, in the air or among the stars”.

“I could see them at any distance and through any intervening object, with as much ease and distinctness as if they were in the room with me, and directly before my eyes. I could see them passing through the floors, and the ceilings, and the halls of the house, from one apartment to another, in all directions, without a door, or a keyhole, or crevice being open to admit them … they were as familiar to me as the forms of my parents and my brother.”

Mischievous and terrible. Among all his visitations, the most welcome was Harvey, a young phantom his own age who appeared from the space between some stair steps. “Every night, after I had gone to bed and the candle was removed, a very pleasant-looking human face would peer at me over the top of that board and gradually press forward his head, neck, shoulders, and finally his whole body as far as the waist, through the opening, and then, smiling upon me with great good nature, would withdraw in the same manner … He was a great favorite of mine; for though we neither of us spoke, we perfectly understood one another, and were entirely devoted to one another.”

Not all of Stowe’s visions were as soothing as Harvey. Some were “always mischievous and terrible” – not human at all, but shapes, moods and presences that vibrated in and out of existence. The largest and most frightening were swirling dark funnel clouds – enormous tornadoes of dread “from ten to 40 feet in diameter” that appeared out of nowhere to terrorize the Lilliputians.

Whenever these “tremulous, quivering” clouds approached Stowe’s human-styled figures (“rational phantoms”), they were thrown into “great consternation” and for good reason. For if one of these funnels so much as touched him or her, the creature would – “in spite of all the efforts and convulsive struggles of the unhappy victim” – change color and be sucked up into the cloud.

“It was indeed a fearful sight to see the contortions, the agonizing efforts, of the poor creatures who had been touched by one of these awful clouds and were dissolving and melting into it by inches without the possibility of escape or resistance.”

Regions of the damned. Inevitably, given Calvin’s religious childhood, hell itself made an appearance. Calvin knew something was up. His friend Harvey wasn’t his usual cheerful self. There “was an expression of pain and terror on his countenance”, as if he were warning Calvin to be on his guard.

“On turning my eyes towards the left-hand wall of the room, I thought I saw at an immense distance below me the regions of the damned as I had heard them pictured in sermons. From this awful world of horror, the tunnel shaped clouds were ascending, and I perceived that they were the principal instruments of torture in those gloomy abodes.”

Staring down into the infernal regions, the boy noted that its inhabitants were “very numerous and exceedingly active”.

Then, “but a little distance from my bed”, young Stowe saw “four or five sturdy, resolute devils endeavoring to carry off an unprincipled and dissipated man in the neighborhood by the name of Brown.” The devils themselves were “in all respects stoutly built and well-dressed gentlemen”, without hair or flesh, but smooth and glossy, and of a “uniform sky-blue color, like the ashes of burnt paper before it falls to pieces.”

The boy’s heart goes out to poor Brown, whose struggles end in his being run through a pair of iron rollers which the devils turn by cranks.

On a more benign note, Calvin recalls a Narnia-like closet, whose open door revealed a “pleasant meadow terminating in a beautiful little grove. Out of this grove and across the meadow a charming little female figure would advance about eight inches high and exquisitely proportioned, dressed in a loose black silk robe, with long, smooth black hair parted up on her head and hanging loose over her shoulders.”

This female would smile and coquettishly draw her hands down either side of her face. Then she would suddenly turn and “go off at a rapid trot … pursued by a good-looking mulatto man, rather smaller than herself … trotting after her.” The “mulatto”, we are assured, “had a mild and agreeable” expression.

Stowe wrote about his childhood visions in 1832 and never put anything as detailed about his invisible world on paper after that. But he experienced similar phenomena into adulthood and the years of his wife’s fame and worldwide travels.

Failure to make hay. Despite his penchant for dense scholarship, Calvin seemed to have been good company, full of jokes and a talented mimic. He never felt the need to hide the existence of his private world from his domestic circle. Harriet and their children took it for granted that while they all sat in the parlor, Calvin’s placid eyes might well be watching “shining people” capering in the fireplace, or an imp peeking out from behind curtains. They loved him anyway, and his household nickname was “Rabbi” in tribute to his great beard and obsession with ancient Hebrew poetry.

What may strike some as most remarkable about Stowe was that even though he was an ordained minister and renowned theologian, he never tried to make spiritual hay out of his visions. When he spoke or wrote about them, it was with an air of bemused curiosity – never implying that they made him special or that he was singled out for special revelation.

“Some peculiarity in the nervous system.” Among Stowe’s correspondents on the subject was Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), author of Middlemarch. To her, he wrote, “Is it absurd to suppose that some peculiarity in the nervous system, in the connecting link between soul and body, may bring some, more than others, into an almost abnormal contact with the spirit-world … and that, too, without correcting their faults, or making them morally better than others?”

Evans, replying to him in a letter to Harriet, suggested that she was more inclined to believe that Calvin’s experiences were “subjective” rather than not. She was telling Calvin, in her kindly way, that it was “all in his head”.

Evans was more circumspect than that summary suggests. She too seemed uncomfortable drawing a sharp line between ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ experience. After all, Stowe’s phantoms were as vivid and consistent a part of his life as his wife and children. They were something he conjured with like the theological doctrines he spent his life elucidating – subjective doctrines that can’t be proven, but which shape reality for their followers.

(Stowe was a great admirer of Evans’ novels, even though she was agnostic and he a self-described “Calvinist of the Jonathan Edwards school”. I think you are a better Christian without church or theology than most people are with both, he wrote her. God bless you!)

Whatever the source of his visions, Calvin Stowe – born in poverty, learned by uncommon diligence, encourager of his wife’s literary ambitions – grew old in the bosom of his fond family, able, thanks to the financial security won by his wife’s pen, to devote his later years to his magnum opus, Origin and History of the Books of the Bible, Both Canonical and Apocryphal: Designed to Show What the Bible is Not, What It is, and How to Use It.

While Origin and History does not question the authority of the Bible, it is generally an effort to demystify its canonical assembly and ground it in human history. Thus Stowe, with an army of sprites, fairies and gnomes looking over his shoulder, joined the movement of late 19th century theologians who sought to strengthen belief in the Bible by stripping it of its fairy tale aura.

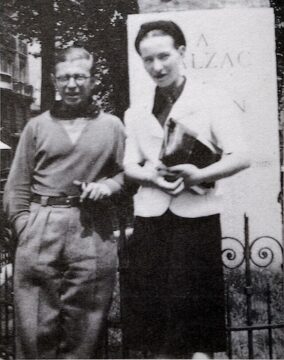

Sartre’s crustacean companions. Stowe wrote this book during the American Civil War. Seventy-six years later, French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre wrote his big book, Being and Nothingness, during another raging conflict: World War Two. These works and their authors have some surprising things in common. Both books are deeply informed, densely written, and both engage the most profound questions of meaning and existence. More peculiarly, Sartre also had “invisible friends” … or maybe not so much friends, as sinister hangers on.

In a 2019 article in The Paris Review (“Sartre’s Bad Trip”), Brian Jay tells how, for a portion of his life, Sartre found himself accompanied by large crabs or lobster-like creatures that he alone could see. These hallucinations are sometimes considered the after-effect of a mescaline trip he undertook under a doctor’s supervision in 1935. The experience was not a good one for the philosopher, who described the effects as “disgusting” in his 1940 study l’Imaginaire.

Jay quotes Sartre, recalling the episode in 1971:

“After I took mescaline, I started seeing crabs around me all the time … I mean they followed me into the street, into class.”

Sartre would interrupt his lectures and bark at the crabs to be quiet like the screwball professor in a comic skit. He went on to have a nervous breakdown and so visited a newly fashionable psychiatrist in his circle – none other than Jacques Lacan. His experience with the analyst (whose writings became an intellectual fad in the late 20th century) was brief, and no more enlightening than his drug trip.

Out of his head. Some say that Sartre’s hallucinations were boosted by the amphetamines he took to accelerate the writing of Being and Nothingness – the same class of drugs we now know was being fed to German soldiers around the same time to speed the conquest of France.

But Sartre’s hallucinations started long before he took drugs. As Jay notes, Sartre confessed in 1971 that, “The crabs really began when my adolescence ended” – well ahead of his bad trip at age 30. So, we may conclude that Sartre’s invisible friends – like those of Calvin Stowe – were not summoned by chemicals but escaped on their own from some tangled place in his intensely verbal brain.

Unlike Stowe, Sartre not only admitted to having a vivid imagination, but he also built a whole philosophy around it. In 1960, he said “I lived in the imaginary long before I understood it philosophically.” Elsewhere, he called imagination “the whole of consciousness inasmuch as it realizes its freedom”.

Whimsical ironies. We might spin this comparison of Stowe, Sartre and their invisible friends out to observe some whimsical ironies. For instance, while Stowe and Sartre were ambitious labored long and hard to produce books that they hoped would have a powerful effect on the world at large, few would argue that humankind is significantly better off thanks to anything they wrote. History moves on and only a handful of books have ever managed to penetrate the consciousness of the great mass of people. Right?

But some books have changed the world, good and hard, and coincidentally, two of them were written by the close female companions of our hallucination-ridden subjects. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin exposed the horrors of Southern slavery and unquestionably hastened its abolition (“So you’re the little lady who started the big war” Abraham Lincoln supposedly said upon meeting Harriet – it didn’t happen, but it makes the point).

Simone de Beauvoir, the 40-year “essential partner” of Sartre, was also an important writer and philosopher. Her 1949 two-part book The Second Sex was the emotional and intellectual launch of what is now called second-wave feminism. And like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, it was a massive worldwide best-seller, whose social effects, down to our own day, are too obvious and pervasive to enumerate.

The two women, each in her own way, reorganized how millions of people understood an entire category of human beings.

Here is a last sort of funny thing to notice. As has been said, Calvin Stowe was initially of the opinion that slavery was something sanctioned by the Bible. But passage of the Fugitive Slave Act so offended his conscience that he reversed his earlier view and joined his wife in embracing abolition and freedom.

Jean-Paul Sartre went in the opposite direction. In his early writings, he opposed authoritarian politics and supported radical human freedom. Over the decades his thinking moved into Marxist channels, and he came, for a period, to support the oppression and virtual slavery of Mao Tse-tung’s China at the time of the Cultural Revolution.

The deeper we gaze into the closet of time, the more the paradoxes multiply. Our field of vision fills with tiny human figures struggling with God, language, and politics – and it’s all so detailed and vivid it almost seems real.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.