by Tim Sommers

“Happiness is that which all things aim at” according to Aristotle. All virtues – arete (ἀρετή) or “excellences” – are the mean between two extremes. We should choose courage over cowardice, sure, but also over being too bold. Stick to the tame middle.

Epicureans and Stoics counsel against risk and in favor of moderation and in cultivating simple tastes in all things.

Confucius was strongly against reckless behavior. The Daoist counseled, “He who knows when to stop does not find himself in danger.”

But it is Jeremy Bentham, the father of Utilitarianism, that I think about when I think about philosophy’s historical distaste for thrill-seeking. According to Bentham the only human good is happiness. Happiness is just pleasure minus pain. Just as we are morally obligated to seek, above all, the greatest happiness for the greatest number, for ourselves we should also want only happiness. Nietzsche retorted, “Man does not strive for happiness; only the Englishman does that.”

Unfair. John Stuart Mill took Bentham’s view of happiness a step further, unintentionally, providing a rare and beautiful thing: an actual argument for thrill-seeking.

For Bentham all pleasures are equal – “pushpin [basically, tiddlywinks] is as good as poetry” – was one of his mottos. Mill was having none of that. Instead, he distinguished between higher and lower pleasures. Higher pleasures like music, literature, and philosophy were not only better than sex, eating, and dirty jokes, lower pleasures, but they also had lexical priority over them. That is, no amount of eating would ever have the same value as listening to Mozart, for example.

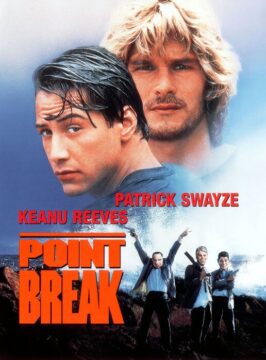

I know. We seem to be going in the wrong direction. But here’s the important bit. How can you tell a higher pleasure from a lower pleasure? Simple, says Mill. You just have to experience both and compare them mentally and you will easily tell the higher from the lower. Mill predictably finds higher whatever is snobbier. But what if we compare surfing to debating philosophy? Impossible? If we take the words of a well-rounded surfer who has done both – like (the character) Bodhi in Point Break – there is no higher pleasure than surfing and no amount of succeeding at work is ever worth a single wave.

Back in the 90s, somebody invited me to a party after a show (The Cramps, I think) and, it being three in the morning, when we got there, no one was left except half a dozen people watching tv. I couldn’t think of what else to do, so I sat down on the floor. The movie they were watching was so bad – and yet so good. It kept surprising me. Finally, I said out-loud, “This movie is stupid. And amazing.” I was widely shushed.

The movie was Point Break (1991).

Johnny Utah (Keanu Reeves), a brand-new FBI agent and former college football star, is assigned to investigate a string of daring bank robberies committed by masked criminals known as the Ex-Presidents. The robbers strike quickly, never hurt anyone, and vanish. Johnny is assigned a crazy partner (Gary Busey) with a crazy theory about the Ex-Presidents. They’re surfers.

Utah learns to surf and goes undercover in the surfing community where he meets the charismatic, philosophical surfer Bodhi (Patrick Swayze). Bodhi preaches freedom, living in the moment, and, most of all, pushing the limits of experience via thrill-seeking. As Johnny becomes deeper embedded in Bodhi’s circle, he learns to surf, skydive, and live the thrill-seeking lifestyle Bodhi embodies.

Bur Johnny eventually discovers that Bodhi and his crew are the Ex-Presidents. They rob banks to finance their endless summer. Torn between duty and friendship (or is it a love of thrill-seeking?), Johnny confronts Bodhi after a robbery goes wrong and several people die, but Bodhi escapes.

Flash forwards a few years. Utah tracks Bodhi to Australia, where Bodhi wants to ride a legendary, deadly 100-year wave. Rather than arrest him, Johnny lets Bodhi paddle out to the wave, knowing it will almost certainly kill him. “He’s not coming back,” he tells the Australian police, then throws his badge into the ocean.

What’s supposed to be interesting about that? Well, first, you really have to see it to get how gonzo it is. Check out the craziest foot-chase in the history of cinema. Did I mention that Johnny jumps out of a plane without a parachute to catch Bodhi? (I am just ignoring their names, which is hilarious for more than one reason.) But I think it’s also serious examination of thrill-seeking as a way of life. Don’t believe me?

It’s directed by Kathryn Bigelow who has made a career making movies about the attractions and limitations of thrill-seeking. She won Best Director for The Hurt Locker (2008), about an adrenalin addicted IED specialist in Iraq. She did an underappreciated cyberpunk film, Strange Days (1995), about a future where “wire dealers” literally sell “wireheads” phenomenological perfect neuro-recordings of other people’s experiences. Talk about cheap, or at least safe, thrills. Bigelow’s other films include House of Dynamite (2025), Zero Dark Thirty (2012), and (second only to Point Break) the Vampires-as-thrill-seekers grindhouse flick, Near Dark (1987). She knows about thrill-seeking.

So, what am I saying Point Break is saying?

The key is that Johnny Utah is just as much a thrill-seeker as Bodhi. He is an FBI agent who used to be a football player. But Bodhi’s thrill-seeking, bank robbing, in particular, crosses a line. But Johnny and Bodhi meet in the middle with surfing and sky diving, but mostly surfing.

Johnny not only likes and sort of admires Bodhi, he sees the appeal of Bodhi’s more extreme pursuit of thrills. He wavers until Bodhi forces Johnny to help them rob a bank and then, in an inexplicable act that is cliché and the biggest defect of the film, suddenly (and for the first time) Bodhi “goes for the vault” and things go wrong.

It is clear even then that Johnny wavers. The only reason he gives to Bodhi for why it’s over is “people died.” Nothing about being a criminal per se. And, as I said, in the end, when Johnny finally catches up with Bodhi, instead of arresting him, he lets him die surfing. That is enough, (apparently) of a karmic rebalancing. Finally, Johnny throws his badge into the surg. But I don’t think it’s because he is giving up on thrill-seeking.

Is it really so hard to believe that people might find risking their health and safety in pursuit of experiences beyond the ordinary worth it? There some legitimate concern about how what they do affects others. But that’s not the real issue. If it were the police wouldn’t run skateboarders off whether or not anyone (other than them) is in danger at the time. If it were it wouldn’t be referred to so derisively (especially in movies) as being an “adrenaline junky.” Why equate kite surfing that requires such high level of fitness with injecting narcotics? What’s so bad about thrill-seeking? “Life is either a daring adventure or nothing.” You know who said that? Helen Keller.