by Steve Szilagyi

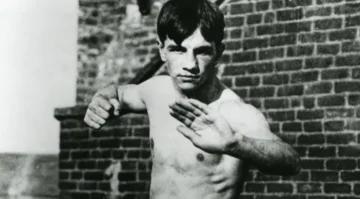

Adolph Wolgast is born on a farm in 1888. Chores make him strong. The company of lumbermen makes him tough. “Little Addie” is not tall. But he can spin his arms like a windmill. And if you are in his vicinity, you’d better hope your chin isn’t in the way.

After knocking down everyone worth fighting in his hometown, Addie hits the road. He is 16. He hops freights, works in sawmills, fights in improvised rings. Falls in with a guy named “Hobo” Dougherty.

“Those are my pork-and-bean years,” he chuckles about his youthful wanderings many years later. By then he can afford to laugh—wearing a bearskin coat that cost a thousand dollars, owning a ranch up in Oregon. A popular man, the lightweight champion of the world. “The most likeable little pug you’re ever going to meet,” one sportswriter called him. And yet—though he has no way of knowing it—Addie is already well along the road that ends in a hospital for the insane, where, on a darkling plain swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, he will face one last grim fistic encounter in the dark.

Little Addie and his buddy Hobo Dougherty land in Grand Rapids in 1906, where they fall in with the fight crowd. He gets taken on as a sparring partner in a gym. The older boxers don’t like him. He doesn’t play pit-a-pat. Once he’s put on the gloves, he doesn’t see any reason he shouldn’t knock the other fellow down.

Fight promoters like the boy’s aggression and put him in the ring. Addie goes pro. He gets booked on undercards. Sometimes he makes as much as $5 a fight. He fights in saloons, “athletic clubs”, basements, vacant lots. Betting is rife. It is cockfighting with humans.

Garish jackets, bleary-eyed pugs. Addie makes good friends in Grand Rapids. Friends who will stand by him in years to come, when his life spirals into catastrophe. But for now, he’s outgrown the place. So he crosses Lake Michigan to Milwaukee, where the fight game is well-stirred into the municipal soup. Colorful promoters with nicknames like “the Millionaire Newsboy” book fights out of candy stands, hotel lobbies, and bars. Here, a journeyman might strike gold with a lucky punch.

A cigar-chewing manager named Tom Jones takes an interest in the boy. Jones knows boxers. At fights, he wears a garishly colored jacket so his bleary-eyed pugs can find their way back to the their corner. He finds a lot to like in Addie, who lives clean and whose love of training shows in softball-sized shoulders and superbly cut torso.

Looking the other way. The world of boxing in 1908 is a circus of hypocrisy. Men pack the ringside and the saloons, even as reformers and ministers denounce the sport outright. Leslie’s Illustrated describes boxing as “a sport which disgraces civilized men.” It is banned or highly regulated in nearly every state. Boxing commissions issue flurries of unenforceable rules. Mayors and sheriffs can be persuaded to look the other way. The whole sport is driven by gambling, which occupies a legal gray zone and goes on openly wherever two or more men gather around a spittoon.

At the highest level are the championship fights, dominated in the teens and twenties by legends like Jack Johnson, Jess Willard, and Jack Dempsey. Below that are club fights with journeymen professionals like Addie at sawmills, county fairs, or the back rooms of saloons.

Young Wolgast never loses his fierce, sloppy aggressive style. But Jones helps him refine it. He moves Addie to California, and books him in a series of fights with a strategic intent: to get Addie into the ring with one particular boxer, the world lightweight champion. Oscar “Battling” Nelson.

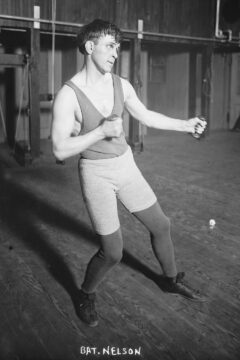

The Durable Dane. Then as now, in the run up to a big fight, one of the two boxers must be characterized as the establishment candidate (Sonny Liston) and the other as the outsider (Cassius Clay). Battling Nelson, “the Durable Dane”, has been lightweight champion for four years. He is heavily favored in every fight and is patronized by men in high places.

Nelson earned his place in the establishment by beating black champion Joe Gans (“The Old Master”) and restoring the honor of the white race. (Ethnic rivalry flourishes, with fighters nicknamed “Hebrew Hammer”, “Boston Tar Baby” or “Polish Prince”.) Wherever Nelson goes people crowd round him. He leads parades, sponsors businesses and is quoted respectfully in the press. President Theodore Roosevelt invites him to lunch at the White House. But Nelson is no sissy.

The Durable Dane can take a punch. The same year that Wolgast fights Nelson, Rudyard Kipling crystallizes the era’s widely held attitudes toward character in his still-famous poem If (“If you can keep your head while all about you are losing theirs … You’ll be a man my son”). Among the unsubtle boxing crowd, Kipling’s steadfastness boils down to ability to stand in one spot and absorb unbelievable punishment without quitting or falling unconscious.

The boxing press believes that Nelson epitomizes this quality. They look down on Nelson’s former antagonist Joe Gans for being a “brainy”, “scientific”, boxer – in other words, shifty. “No science for me,” Nelson brags. “I’m a human punching bag.”

Nelson defends his title and collects purses in fight after fight. Meanwhile, the press is building up a new outsider to fight Nelson – Addie Wolgast, now the “Michigan Wildcat”. Sportswriters of the day try to outdo each other in wild hyperbole leading up the fateful meeting. The 5’4” inch Addie and 5’7” Nelson are portrayed as titans on the scale of Hector and Achilles.

“They hate each other’s guts.” Little Addie fights and wins more than two dozen bouts between 1908 and 1910. He shows that he can absorb a battering as well as any man. Everyone agrees he earns a shot at Battling Nelson for the title – and he gets it. The fight takes place outdoors on a rainy day in Richmond, a ramshackle town outside San Francisco. Tickets are $85, and more than 10,000 people have made the awkward journey by train or ferry to the site.

In the weeks leading up to the fight, newspapers do their best to whip the public into a frenzy – though it can be difficult to heighten contrast between the two men. Sportswriters can’t play the ethnic angle. Both men are midwesterners of Teutonic heritage. Both men fight in the same style, close-in, head-to-head, delivering piston-like punches to the face and body. Neither has much respect for prohibitions against head-butting and low blows. “They’re so much alike,” observes one sports writer, “that they hate each other’s guts”.

Addie shows his confidence by offering to let Nelson fight him with horseshoes in his gloves. The standard boxing glove of that time is something like the padded mittens skiers wear today. The glove is not so much intended to soften blows, as to prevent a fighter’s knuckles from being flensed by the other man’s jaw and forcing an early end to the entertainment.

Rain and mud before the blood. On the day of the fight, it rains all morning. Ticket holders have to make their way across a muddy field to reach the temporary grandstands. Thirty minutes before the scheduled start, Addie is racing around the countryside in a fast car, too excited to lay down on a massage table. When he finally settles down enough to enter the ring, Nelson – to psych him out – makes him wait fifteen minutes. Then he makes a grand entrance riding the shoulders of Abdul the Turk, his colorful cornerman.

Addie crosses the ring and tells him, “He carried you in, and he’s going to carry you out.”

Nelson sneers and looks Addie up and down. “Big talk for a little man.”

The referee calls them to the center of the ring to receive instructions. But Nelson interrupts him. “No fouls,” he tells the ref. “Stand back. Anything goes.” Wolgast agrees to this private “no rule” agreement, and right up until the end the ref does nothing to pause the mayhem.

What follows is still remembered as one of the longest, most primitive and brutal fights in the history of modern boxing.

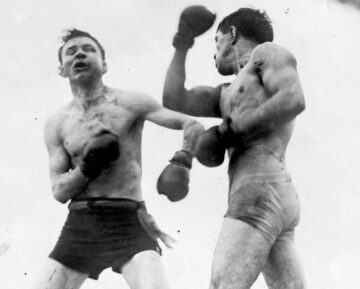

The mighty Nelson is accustomed to toying with his opponents in the early rounds, letting them flail while he measures them, and then putting them away with a hook when he tires of the sport. But from the opening bell Wolgast gives him no such leisure. He smothers the Dane in a cloud of fists, drives him backward and sideways, and forces the fighting at every step.

Nelson’s lip splits early. Soon after, Wolgast’s nose cracks audibly under a counterblow, but the younger man never slackens. By the seventh round Nelson is staggering, though he finds strength enough to land a blow to Wolgast’s head that looses a torrent of blood from the challenger’s cauliflower ear.

By the thirteenth round Nelson’s face and chest are smeared with his own blood, and it appears only a matter of moments before Wolgast will finish him. But, as one boxing writer later observes, it is “a battle between two egotists”—two men resolved to die on their feet rather than fall at the other’s.

After the twentieth round there can be no doubt that Nelson is getting the worst of it. “Nelson takes punch after punch in the face and ribs until he looks like a great chunk of round steak down as far as the belt,” writes Richard S. Davis years later in the Milwaukee Journal. “It is almost like a child pushing his fists into a mud pie.”

Then comes the shock of the fight. In the twenty-second round Nelson catches Wolgast flush on the jaw and sends him to the canvas “as if felled by an axe.” For an instant the end seems at hand. But the Michigan Wildcat staggers to his feet, shakes his head clear, and goes back at the champion with renewed fury, carrying the battle for eighteen more rounds.

By the thirty-ninth Nelson can scarcely lift his arms. His mouth is grotesquely swollen, his eyes narrowed to slits, and the battered side of his face has lost all human contour. Blood spatters the ringside seats. Hundreds of spectators have already left, disgusted by the brutality of the spectacle.

The danger is real. Only nine years earlier lightweight Mike Ward dies from blows to the head in an eighth-round bout—the third ring fatality in as many years. Now Nelson, scarcely able to defend himself, stands helpless as Wolgast prowls about him, jabbing and striking almost at will.

In the fortieth round the referee at last intervenes and stops the contest. Wolgast is declared the winner. He leaps from the ring and runs through the mud like an excited schoolboy, while Nelson—just as Wolgast has predicted—is carried out in the arms of his Turk.

Popular with the ladies. Now the youngest lightweight champion in history, Addie doesn’t forget his old friends. He picks up every check, buys old buddies like Hobo Dougherty stickpins topped with gold nuggets, and spreads his considerable new wealth around. (Addie has placed huge bets on himself to win, and makes more money gambling than through purses.) He goes to Detroit, where he is given a tour of the Ford factory and his pick of fine automobiles. Gossip columns note that he is popular with the ladies, who stuff his mailbox with letters.

Coming from a large, loving family, Addie buys his parents a new farm in Michigan, and parks some of his winnings in their care. But his first move after winning the championship is to go onto the vaudeville circuit, because in 1910, vaudeville is the world. Everybody in the public eye eventually turns up on the vaudeville stage: boxers, explorers, politicians, the virtuous and the notorious. Addie fights exhibition bouts on stage and narrates the popular newsreel film of his big fight. (Battling Nelson also goes on a vaudeville tour once he’s recovered, telling his side of the story and basking in his still-robust popularity.)

Ups and downs, mostly downs. Then Addie climbs back into the ring. It is estimated that he fights 40-45 times over the next seven years – a number for which the word staggering is appropriate in every sense. These years are a zany period for the Michigan Wildcat:

- He gets married in 1911 and announces that he will quit boxing once he’s taken care of the few worthy opponents on the horizon. (He does no such thing.)

- He helps make history in a fight with “Mexican” Jake Rivera, when both men land simultaneous haymakers, and knock each other out cold – boxing’s only verified double-knockout.

- After he loses his championship to Willie Ritchie in 1912, he complains, “How could I lose to a guy with a name like Willie?”

- He goes to a plastic surgeon and has his flattened nose successfully rebuilt with paraffin. One day, he notices a pimple on his nose and squeezes it. He keeps squeezing until he’s squeezed all the paraffin out, and his nose deflates into its former state.

- Wolgast is adamant that he won’t lower himself to fight Sam Langford, Joe Wolcott or any other black fighter.

- On the eve of a big fight, he is stricken with appendicitis (“Lightweight champion near death”, says one headline), followed by a long case of pneumonia. He goes back into the ring, perhaps before being fully healed.

- He is famous for being knocked down and bouncing right back up, like silent film comedian Buster Keaton (a contemporary with the same height and build as Wolgast).

- Reporters notice that Wolgast “does not seem to know where he is at times”, that he fights “without plan or intelligence” and relies on head-butting and mauling because his timing is gone. Some mention that he should not be fighting.

- Addie blows through a fortune estimated at $250,000 over five years. He disappears for weeks at a time, roaming the mountains and woods of northern California and Oregon. He wanders into some small town and begs for food. Those who encounter him describe him as gentle, polite, and more muscular than the usual hobo.

- His parents still have the money he’s parked with them, and they arrange visits to doctors and brief stays in sanitariums.

- His wife is scared of him. In 1917, she files for a protection order, and a Wisconsin court finally rules that Addie is legally insane. Five years later, his wife files for divorce.

From mush to milkshake. The accumulated effect of the hundreds of blows Addie receives to the head (or inflicts on himself by using his head as an offensive weapon) before and after the fight with Nelson has turned his brains to mush. Amazingly, even after 1917, there are promoters and managers crass enough to put the former champion on fight cards – and audiences sit back to watch whatever is left of Addie’s brain get turned from mush to milkshake. Over his lifetime, he fights some 123 bouts.

Finally, in 1927, he is committed to the first of several asylums for the insane in California. He believes he is still lightweight champion of the world, and imagines he is still in the midst of his legendary fight with Battling Nelson. Among the few visitors are his old pal, Hobo Dougherty, who gets him a furlough to see a Joe Louis fight. It’s customary for ring announcers at big fights to introduce former champions sitting at ringside. But Addie’s condition is an embarrassment to the fight game, and his presence is ignored. Over the next two decades, his mental and physical condition deteriorates. The public forgets him. But he never forgets who he was – and still thinks he is. Every so often, the quiescent patient surprises hospital personnel by suddenly snapping into a boxer’s pose, bouncing on his toes, and jabbing at some phantom opponent.

It is speculated that this habit may be what provokes his brutal beating by hospital attendants in 1949. One day the morning shift discovers 61-year-old Addie lying unconscious on his bed with three broken ribs and bruises all over his body. Police are called in. The two attendants who’ve been on duty that night are arrested. Before they can go to trial, there is a strange twist: One of the arrested men goes berserk in the courtroom as he is being arraigned. We imagine him screaming, throwing legal papers, overturning tables – he is quickly declared insane and made an inmate in the very hospital where he’s worked and presumably beaten the crap out of Addie. The other man arrested is acquitted and is re-hired at the hospital.

The last round. In the 1940s, Wolgast’s greatest opponent, Battling Nelson, has also run through his fortune and is working as a clerk in a Manhattan post office. Newspapers report that the post office plans to lay him off, and that Nelson is applying for a government pension based on a dubious claim of service in the Spanish–American War. Soon after, dementia comes for Nelson, and he too winds up in an institution.

By the time Addie dies in 1955, he is blind, weak, and barely sentient. He receives an obituary in Time. One newspaper writes that after the Nelson fight, Addie spent fifty years on “Dream Street.” No. It was much worse than that.

[Contemporary boxing writers like Richard S. Davis and Pete Ehrmann have written excellent articles on Wolgast’s career. I highly recommend Arne K. Lang’s book, “The Nelson-Wolgast Fight and the San Francisco Boxing Scene, 1900-1914” Lang’s deadpan descriptions of the larger-than-life characters and outrageous situations that typified the era made me laugh more often than anything I’ve read in years.]

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.