by Mike Bendzela

The important thing to remember about “extraordinary popular delusions” (in Charles Mackay‘s words) is that there is nothing you can do about them. And they are legion. The best you can do is avoid them, and this takes diligence and a certain resolve: The subject gets changed. The screens go off. No television comes near your eyeballs. The radio is switched to a music station. “Social” media are eschewed. And when people needle you about your lack of engagement, you ignore them. Whose approval do you think you need anyway? Let the rowdies enjoy their bandwagon in peace. I’m wondering whether the time will come when the shiny new plagiarist technologies undermine themselves to the point that nothing seen on a screen will be trusted anymore, when electronic becomes a synonym for fake. It’s an open invitation to reclaim such quaint sensual pleasures as face-to-face conversation and the scratch of pencil against paper.

Bogus seems to be the new name of the game: One pops in an assignment description, and out pops a tidy little poem with one’s name in the byline, ready to be safely uploaded to the class website. Therefore, in my writing classes I am taking steps to get away from screens, which means increasing the use of paper and pens/pencils. One must walk forward into the past. One learns that to be a writer one scribbles and fails, scribbles and fails. For the same reason that most business ventures shutter and most species go extinct, most writing never sees the light of publication. The learning is in the doing, not in the dung heap at the end of the process. Why take a cooking course if you are just going to order out? Why take a technical rock climbing class (as I did as an undergraduate geology major) if you are only going to hire a helicopter to fly you to the top of the peak?

Gosh, how does my online article about this subject square with itself ?? It may make for an interesting classroom discussion of irony and paradox. The class is the process. This article? The dung heap at the end of the process.

I went to graduate school to discover that I couldn’t write a good poem to save my life, which is why I tell my students, “Your poems are permitted to suck.” Sucking at something is no reason not to give it a go. One thus learns how difficult that something is. And one comes to appreciate good poets. Failure is almost certainly underrated. In college I tried mathematics (Analytic Geometry and Calculus) and failed, so I took a lower level course, persisted, and “passed” (quote unquote). I ended up dropping my geology major as a result of the experience, because proficiency in math was required and this was too difficult for me. An important lesson was learned. . . . But if sucking at math caused me to abandon a major in science, why didn’t sucking at poetry cause me to abandon English literature? Fiction writing, in short. And when fiction writing failed (after college), there was always nonfiction, where I am currently most happy (q.v.). Forking paths, to be appreciated, must be walked, preferably barefoot.

*

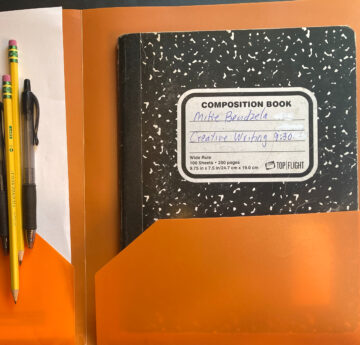

As the photograph of the notebook accompanying this article illustrates, I participate in assignments along with students. The four modules of the class are Verse, The Tale, Memoir, and The Writer’s Notebook. The notebook has always been required in my creative writing classes, but over the last year it has begun to bear more of the weight of the final grade: This past fall semester the notebook counted for 40% of the grade, up from 25% the semester before. This spring semester it will count for 50% of the grade.

Assignments are given to be written longhand, which become stealth drafts for poems and parables. For instance: Spend two pages describing in sumptuous detail a natural object or place that is special to you. Do not explain to us what is special about it. Simply give the details. Later, after the class has annotated such nature poems as “The Fish” by Elizabeth, Bishop; “A Narrow Fellow in the Grass,” by Emily Dickinson; and a few poems by Robinson Jeffers, this journal entry is gleaned for several of its loveliest sentences, which are then arranged on the page, like objects in a tableau, to form a poem. I have stopped saying, “Write a nature poem!”, which may induce paralysis or a gleaning expedition online.

So I wrote in my notebook about a porcupine that was in the process of destroying trees in our little orchard. He or she even left his or her calling card:

This is a Rhode Island Greening apple with several quills sticking out of it. I couldn’t believe it — the perfect “natural object” to write about! Scribble, scribble in my notebook until I had over a page of writing. Then I began to pluck lines up off the page, and lay them back down on another page, shuffling lines around, breaking them at interesting places, adding capital letters at the heads of lines, jiggling lines together until they rhyme, or sort of rhyme, trying out end-stops, enjambed lines. I added a nod to Genesis and to Robert Frost’s “After Apple Picking”, which we had annotated together in class. Eventually, I had a draft of a poem I would call “Heritage Apple”:

Picking Rhode Island Greenings from a ladder

I notice an apple bristling

Among the leaves & branches. I pick it

And hold it in my open palm, marveling,

Observing several, maybe a dozen, quills,

Like pins in an emerald green pincushion, standing

Firm in the flesh. Nearby,

Two or three apples exhibit bitten flanks,

Rapidly browning but still-fresh teeth marks,

Wasted apples. And there are apples

On the ground, and broken branches & leaves.

Not good signs, these.

These, in fact, portend woe, for I know

What havoc a porcupine can wreak on trees.

Barbed apple in hand I descend

With that sinking feeling

With the knowledge that I’ll arise before dawn

With a loaded .22 pistol in hand,

Remembering —

We have been banished from the Garden and now

Our heritage is to tread cursed ground

And toil in a world where life consumes life.

Then it’s off to The Tale. I have given them a notebook assignment: Scribble for a page or two about an incident in which you were confronted with a problem or dilemma, no matter how trivial, no matter whether you solved it or not. Meanwhile, in class, we look at fables and parables, studying their forms and formulae. We scribble names of random animals on pieces of paper, put them in a bag, then write spontaneous fables into our notebooks about the animals we have drawn from the bag. We read them aloud around the room and laugh, and I frequently have to remind them: What’s the moral of the story? And suddenly they are stumped and truly thinking. We look at some capital L literary parables: Andersen’s “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” Gospel of Luke’s “Parable of the Prodigal Son,” Aesop’s “The Shepherd Boy & the Wolf.”

That notebook assignment? I have them shift the narrative point of view to third person and recast themselves as a fictional character in the story. They may change anything about themselves, the situation, or other characters, and then present it as a parable. If I tell them to write a parable, they might freak out or be tempted to open up the jaws of their laptop and stick their head right in. But have them scribble down a problem they have actually faced then change the point of view . . . et voila. I have done this many times in my own book of fables and parables*:

The fretful farmer remembers being a boy who wanted to grow crops like his grandpa before him. He chose the mighty potato, Red Pontiac.

Grandpa provided the land and the proverbs: “You need rich soil but stay away from sod! Don’t ever add lime. And mind the beetles!”

So, at age eleven, the incipient farmer took over a slope of the backyard where his grandfather had ripped out some juniper bushes and prepared his potato bed.

He dug some ancient compost out behind his grandfather’s dilapidated chicken barn and worked it into the soil. He cut the “seed” potatoes by hand and positioned each “eye” into the dirt, looking upward, and mulched the rows over with rotted hay.

By late summer, he was digging beautiful pink jewels out of the ground. No beetles!

At age twelve, the young farmer planted a larger crop, and a few Coleopterans showed up to the party. But he was diligent, and he picked virtually every beetle off the leaves in time to rescue the potatoes from destruction.

At age thirteen – now sporting a tiny red beard in the garden – the young farmer watched and fretted as armies of Colorado potato beetles triumphed over the Red Pontiacs.

That’s my version of the assignment, rendering a common problem I have growing things — exponentially increasing pest pressures — and fictionalizing until I have an economical little tale, a parable. (I made up the stuff about “Grandpa.”) Because it’s a parable, not a fable, we can just let the “moral” quietly sink in, whatever that may be.

*

An ongoing, indeed weekly assignment that I have them scribble in their notebooks I call “Language Observations.” Students simply have to keep their ears and their eyes open and pay attention to what they hear spoken around them or what they see in various media. Few things are more important for a writer than learning to develop an ear for the language. I give them a list of things to think about: Pet peeves, errors, or malapropisms that irritate students; jargon or slang that show one’s membership to a special social group; the effects of social media on language, etc. I try to have one session every week when we read these entries aloud to each other.

Sept. 9 Language Observation

One of my favorite features of American slang is the use of the suffix “-ass” as an intensifier. I suspect those from Great Britain, for whom American English is virtually a foreign tongue, would find this phenomenon baffling. In America, “ass” means the buttocks or rear end. In England, “ass” retains its original meaning of donkey, or beast of burden. “Sitting on his ass” in England is something Jesus did upon entering Jerusalem. In America, it means he is lazy. England has “arse” and “bum” to mean what Americans mean by “ass.” But most interestingly, in America “-ass” is added to all sorts of adjectives to make them more pungent: “big-ass,” “hard-ass,” “bad-ass,” “nasty-ass.” “Big-ass” means simply very large, probably originally intended as an insult to someone who is overweight. A “hard-ass” as a noun is someone, especially a male, who acts like a tough guy. “Bad-ass” is an adjective for something done to an extreme. “Nasty-ass” is sort of self-explanatory, and it has a nice assonance besides, pun intended. Bad-ass assonance, if you will. You can add “ass” after possessive pronouns to mean something like “self.” You might hear something like, “I told him to keep his ass away from my girlfriend,” or, to someone dawdling in traffic, “Lady, why don’t you move your ass??” It’s frequently added to anything to underscore the speaker’s contempt for something: “Isn’t his big truck a hoax, with its fake-ass exhaust stacks,” or “It takes one mean-ass woman to talk to you like that.” Now that this writing assignment has taken on big-ass dimensions, I think I’ll take my ass on out of here. I told your ass American slang is a weird-ass phenomenon.

Why not have fun with such assignments? If writing can’t be enjoyable, why even do it? That’s why I refer to writing in the notebook as “free writing”: They are free to write as they will, free of an instructor’s intrusive written commentary and corrections.

After weeks of writing like this, students find the Memoir almost second-nature, coming later in the semester as it does when everyone is relaxed and familiar with one another and thus more apt to be more open in their writing. To underscore this atmosphere, we watch several writers presenting their work for The Moth radio series, whereby personal stories are recited before live audiences. The performance aspects of creative writing are thus underscored without having to be spoken of. We look at live readings by masters in the form such as David Sedaris, switching between writers with the text in front of them and others who have a more extemporaneous approach. My favorite in this genre is Maine State Warden Service Chaplain Kate Braestrup’s startling memoir/essay called The House of Mourning, about her having to deal with the parents of a little girl who wants to see her young cousin’s body after he has been killed in an all-terrain vehicle accident.

An added recursive curveball I add to the notebook assignments: We will write about any story we have heard told aloud, further making language the subject of our writing, meta-writing: Just write down what you notice, in the order you remember it, about what the writer has said and how she has said it, using the language of literary description.** After hearing a presentation, I set my timer and we all write non-stop in our notebooks for seven minutes, trying to recall as best we can the literary tricks of the trade these writers use in their memoirs. Over the semesters, I have written about Braestrup’s piece many times, because I always participate in these in-class writing sessions [listen to Braestrup’s extraordinary story first, at the link above]:

The structure of this memoir is amazingly complex, as Chaplain Braestrup combines personal experience, background information (backstory), biblical narrative, and firsthand testimonials to compose a unified piece that is stunning in its emotional impact. She begins with the problem: The parents of Nina (5) tell Kate that the girl wants to visit her dead cousin Andy (6) at the funeral home. It’s a real problem for a chaplain. Braestrup then goes off on a long excursion into backstory and personal history and we wonder, “Why?” It becomes clear she has the experience — personal and professional — to deal with such a request. Her stories about her experiences preparing members of the Maine Warden Service for confronting “al fresco homicides or suicides,” and her amazing account of having to deal with her own husband’s dead body, make it clear that she is uniquely positioned to guide the parents in their decision about whether to let little Nina see her cousin’s body. All this backstory establishes Braestrup’s authority, which matters for her as a writer as well as as a chaplain. Also, this digression, as it were, allows her to delay the resolution of Nina’s story, creating in the audience an immense sense of anticipation. So, when Braestrup pauses long and says, “OK, but Nina was five,” thus returning to the main thread, we are more than primed to hear how the story turns out.

Memoir is a vast genre, part of the even vaster category of nonfiction, partaking of many techniques, such as narrative, reportage, exposition, interior monologue, etc. In students’ writing I see personal experience enhanced with writerly reflection, dialogue juxtaposed against stream-of-consciousness, dramatic scenes punctuated with commentary. This all happens spontaneously. They don’t need no stinking machines.

Notes

*from Metazoan Variations: Evolutionary Fables and Other Emblematic Tales. Ellicott City, MD: UnCollected Press, 2020.

**Rosemary Deen and Maria Ponsot, Beat Not the Poor Desk: Writing: What to Teach, How to Teach it, and Why (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1989). A colleague gave me this book decades ago, and from it I have learned about the importance of “free writing” in notebooks and about writing observations in class about works we have heard read aloud.

Images

Photographs by the author.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.