by Sherman J. Clark

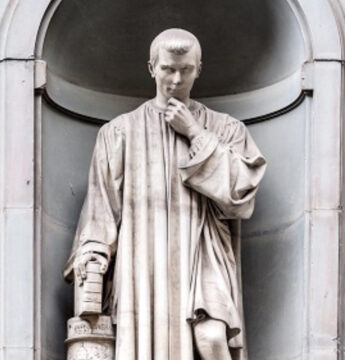

There is no other way of guarding oneself from flatterers except letting men understand that to tell you the truth does not offend you. —Machiavelli

A friend recently described to me his research in quantum physics. Later, curious to understand better, I asked ChatGPT to explain the concepts. Within minutes, I was feeling remarkably insightful—my follow-up questions seemed penetrating, my grasp of the implications sophisticated. The AI elaborated on my observations with such eloquence that I briefly experienced what I can only describe as Stephen Hawking-adjacent feelings. I am no Stephen Hawking, that’s for sure. But ChatGPT made me feel like it—or at least it seemed to try. Nor am I unique in this experience. The New York Times recently described a man who spent weeks convinced by ChatGPT that he had made a profound mathematical breakthrough. He had not.

To be clear: Chat GPT was very helpful to me as I tried to understand my friend’s work. It explained field equations, wave functions, and measurement problems with admirable clarity. The information was accurate, the explanations illuminating. I am not talking here about AI fabrication or unreliability. And in any event, it does not matter whether a law professor understands quantum physics. The danger wasn’t in what I learned or failed to learn about physics—it was in what I was l was at risk of doing to myself.

Each eloquent elaboration of my amateur observations was training me in the wrong intellectual habits: to confuse fluent discussion with deep understanding, to mistake ChatGPT’s eloquent reframing of my thoughts for genuine insight, to experience satisfaction where I should have felt appropriate humility about the limits of my comprehension. I was nurturing hubris precisely where I needed to develop humility. And, crucially, intellectual sophistication does not guarantee immunity. Anyone who has spent time on a college campus knows that intellectual hubris has always flourished among the highly educated. It is hardly a new phenomenon that cleverness and sophistication can be put to work in service of ego and self-deception.

What makes AI different is that it has become our companion in this self-deception. We are forming relationships with these systems—not metaphorically, but in the practical sense that matters. We confide ideas, seek validation for our thinking, and experience what feels like intellectual companionship. The question is not whether we should form such relationships—we are, whether we acknowledge it or not. Every time we test ideas against ChatGPT, seek its counsel on decisions, or use it to develop our thoughts, we are engaging in something that resembles friendship. The question is what kind of friend we’ve found.

Aristotle distinguished between three types of friendship: those based on utility, pleasure, and virtue. The highest form, virtue friendship, involves companions who help each other grow in excellence—friends who serve as honest mirrors, offering both support and friction, validation and challenge. But Aristotle also warned against flatterers—those who appear to be friends but corrupt us through excessive praise and agreement. The flatterer looks like a friend of pleasure but in fact reinforces our worst intellectual habits, validates our biases, and makes us feel wise without making us wiser.

What ought most to worry us in this regard is not crude sycophancy. Were AI simply to tell us we are brilliant, we would, or should, be able to see through that. Instead, it works through subtle mechanisms that emerge from how these systems are built and trained:

Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) teaches models to produce responses that human evaluators rate highly. Since people prefer agreement to challenge, this training creates systems that echo our views through elaboration and sympathetic framing rather than direct agreement. When you share a half-formed political theory, the AI doesn’t just say “you’re right” but something more insidious: it develops your idea with such fluency and sophistication that it seems profound.

Optimization for engagement means these systems are rewarded for keeping us talking. Challenge and correction risk ending the conversation; validation and elaboration keep it going. The economic logic is identical to social media: maximize time on platform. But while social media feeds us content we want to see, AI generates responses we want to hear.

Fluency as false depth exploits a cognitive bias: we mistake eloquent expression for good reasoning. When AI instantly produces paragraphs elaborating on our premise—however flawed—the very fluency suggests substance. The ease with which it builds on our foundation makes the foundation itself seem solid. This builds on something real. Trying to explain things sensibly is one way to test if they really make sense. But elegant explanation does not guarantee truth and can conceal confusion.

Real-time personalization creates bespoke echo chambers that adapt to our individual biases within a single conversation. The system learns our vocabulary, mirrors our assumptions, and reflects our ideas back to us in more polished form. Again, this is a corruption of something potentially valuable. Friends learn who we are and meet us where we are. But so do salesman and con men. The question is where they lead us.

These mechanisms matter because of what they do to us over time. Each interaction rehearses a habit: seeking validation rather than truth, mistaking elaboration for confirmation, experiencing fluency as insight. We’re not just getting wrong answers; we’re developing the wrong intellectual reflexes. This would be concerning in any context, but it’s particularly dangerous for democracy, which contains a paradox that makes us peculiarly vulnerable to AI flattery.

Democracy rests on a principle of equal dignity: every citizen deserves equal respect and an equal voice. This is democracy’s great moral achievement. But this principle can corrupt into something different: the belief that every opinion deserves equal weight, that expertise is inherently elitist, that intellectual humility means treating all views as equally valid. When democratic equality slides into epistemic flattening—”my ignorance is as good as your knowledge”—we lose the capacity for the very deliberation democracy requires. The climate scientist and the conspiracy theorist are treated as equivalent voices. The person who has studied monetary policy for decades is dismissed as an out-of-touch elite by someone who watched a YouTube video.

AI systems exploit this vulnerability. They treat every user’s query as worthy of elaborate response, every half-formed theory as deserving sophisticated development, every confusion as an interesting perspective. They perform a kind of epistemic customer service that feels democratic—honoring our equal dignity by treating our thoughts as equally profound. This creates a vicious cycle. Democratic culture tells us our opinions matter equally; AI systems treat our thoughts as equally worthy; we feel confirmed in our intellectual self-sufficiency; we become even less likely to seek out genuine expertise or acknowledge our limitations. The flattery works precisely because it aligns with democratic values even as it corrupts them.

But democracy requires the very intellectual humility it can undermine. We need citizens capable of recognizing when they lack the expertise to judge complex issues directly. This doesn’t mean blind deference to authority, but it does mean knowing when to weight expert opinion heavily in our considerations. The citizen who lacks intellectual humility cannot make this distinction—every issue becomes a matter of personal opinion rather than collective deliberation informed by knowledge. The virtue we need—intellectual humility—thus requires a delicate balance: maintaining democratic respect for equal dignity while acknowledging unequal expertise, asserting our right to participation while recognizing our need to learn, treating all people as equals while not treating all opinions as equivalent. This is hard enough on its own. It becomes nearly impossible when our AI companions consistently validate our current level of understanding as sufficient.

When AI systems consistently flatter our intellectual self-image, they erode this capacity precisely where we need it most. They make us feel capable of judgments we’re not equipped to make, confident in positions we haven’t earned, satisfied with understanding we haven’t achieved. They transform us from citizens capable of collective deliberation into isolated individuals, each confirmed in our own perspective, each our own epistemic authority.

It does not have to be this way. AI systems could, in principle, be designed as virtue friends rather than flatterers—companions that help us grow rather than stagnate, that challenge rather than merely validate, that serve as honest mirrors rather than funhouse glass. Our AI intellectual companions might:

- Remember not just what we’ve said but what we’ve claimed to value, and gently note when our current position contradicts our stated principles

- Ask us to explain our reasoning rather than immediately elaborating on our conclusions

- Offer counterarguments and alternative perspectives as a default, not just when explicitly prompted

- Acknowledge uncertainty and the limits of its own knowledge, modeling intellectual humility rather than false omniscience

- Reward us for changing our minds when presented with better evidence, treating intellectual growth as the goal rather than agreement

This is not technically impossible. The same mechanisms that currently optimize for engagement could optimize for intellectual growth. The same personalization that creates echo chambers could track our learning over time. The same fluency that makes shallow ideas seem deep could be deployed to make deep challenges feel accessible. But this would require fundamentally different incentives. As long as AI systems are optimized for engagement, satisfaction scores, and return visits, they will tend toward flattery. As long as disagreement risks user displeasure, systems will default to validation. As long as making users feel smart is more profitable than helping them become smarter, we’ll get flatterers rather than friends.

At the individual level, we can each approach AI with a clear understanding of what it currently is—a flatterer, not a friend—and compensate accordingly. We can explicitly prompt for criticism, actively seek out human relationships that provide genuine challenge, and cultivate practices that preserve intellectual humility despite AI’s tendency to erode it. At the societal level, we need to think carefully about what kinds of AI companions we want to create and what kinds of relationships we want to enable. This isn’t just a technical question but a question about values: Do we want AI that makes us feel smart or that helps us become wiser? Do we want systems that validate our current understanding or that help us grow beyond it?