by Jochen Szangolies

I have once again been thinking about power, and once again I feel ill at ease with it. Yet while I do consider myself somewhat badly equipped for this pursuit, I nevertheless feel, “in these trying times”, a certain responsibility to not cozy up with pursuits closer to my heart and talents, but invest some portion of my time and ability into examining the mechanisms of control as they are exerted in the world. After all, as before, one may hope that slow and steady going may substitute for knack and knowledge, and perhaps even help those otherwise sidelined to enter the conversation.

The prompt for the present swerve out of my lane was provided by a colleague’s lunchtime question, after the conversation had inevitably landed on the topic of what flavor of future dystopia awaits. “But how,” he started (or nearly enough so), “are the billionaires in their bunkers going to keep themselves in charge?” After all, what’s to stop the armies of servants they depend upon to uphold their lavish lifestyles from just, well, murdering them and taking their shit?

The question invites an immediate followup: what’s stopping us now? Not murdering, as such—but even just applying equal standards to the wealthy stands to free up resources capable of addressing a great many injustices in the world. According to a recent estimate by the US Department of the Treasury, the top 1% of earners dodge about $163 billion in annual taxes. (If you, like virtually everyone, have trouble conceptualizing these sorts of numbers, I find it helps to convert them to time scales: if a dollar is a second, then a million dollars are about eleven and a half days, while a billion dollars are roughly 31.7 years; the avoided sum of taxes then takes us back 5165 years, back to when the first phases of Stonehenge started construction. By contrast, the median US income for a full-time worker is about $63,000, or roughly 17.5 hours.)

Clearly, there is much good that could be done with that sort of money. As a semi-random example, according to estimates it would take from 10 to 30 billion dollars annually to end homelessness in the US, essentially eradicating a major source of suffering. And nobody would have to get murdered—or even unduly inconvenienced: this is money that is already legally owed, simply by having the 1% pay their fair share. Studies project an added revenue of up to $12 dollars per dollar invested in audits of high income individuals. So why aren’t we out there demanding equal treatment for the wealthy?

Substantially, this is the same question as the one about the billionaires in their bunkers, just shorn of its apocalyptic flair. We could band together and level the playing field to the benefit of virtually all of society; yet, we don’t. Somehow, small elite groups of people are capable of defending their privileged status against the overwhelming majority of the population. They are able to wield, and hold on to, power: the capacity of making their will manifest—of not having to accept ‘no’ for an answer. (With their inability to do so often being a shared characteristic with small children.) In a previous column, I have tried to elucidate the how of power: how what ultimately reins it in is reality, and how we have seen a consequent obfuscation, weakening or outright negation of reality to better serve power’s interest. In this essay, I will thus have a look at power’s why: why it is that small groups of people can wield it against the interests of a much larger majority.

Pernicious Proxies

Before embarking on this practical pursuit, let us quickly deal with a normative stumbling block: perhaps, one might hold, a capable elite in fact should hold power over the unwashed masses. Perhaps wise philosopher kings could announce just rulings, genius entrepeneurs create universal wealth, central committees plan optimal distributions. Perhaps also, coming at this from the other direction, ordinary folks are simply not capable of self-governance, and without a sovereign, a Leviathan, devolve back into ‘nasty, brutish, and short’ existences.

I will not rehears the back and forth for either perspective here, but instead make the case that we should be optimistic about people’s capacity to self-govern, because from a simple pragmatic point of view, centralized power structures always eventually diverge from even the best of intentions. The reason for this is an argument I have made repeatedly in these pages: breaking down complex systems to easily tracked quantities and attempting to optimize them causes these quantities to diverge from the complexity they seek to summarize. This is the main driving force of the Monkey’s Paw-effect of the previous column: if you break down the complex well-being of an entire society’s worth of individuals to an easy to estimate quantity, such as mean wealth, GDP, or what have you, and implement policies to narrowly optimize this quantity, then there are many more ways of doing so that break the connection between individual well-being and your proxy than there are ways that uphold it. As a result, we get an entropic slide away from what we really want (most people being mostly fine most of the time), while being presented with what we thought we want to the letter (an increase in mean wealth, say).

But centralized power structures can’t help but rely on highly abstracted, summarized and dimensionally reduced data to quantify their policies. Consequently, such power structures will in the end favor optimizing these data over improving more nebulous measures, such as individual satisfaction or quality of life or subjective experience of meaning, and so on. The consequence of this is that if one cares about these measures—and as an individual within society, it is simply self-care that one should—centralized power structures are an ineffective means to achieve these goals. In the end, thus, the only legitimate source of power over the people is from the people, and we can only hope that they’ll prove up to the task.

Of course, we have long understood this, at least when it comes to political power: there is a broad consensus these days that the most desirable form of government is the one Churchill famously considered the worst (except for all the others), namely, democracy. But I believe where we have yet to catch up is that power is not exhausted by political power. Thus, the diagnosis by Francis Fukuyama that with the widespread adoption of liberal democracy we had reached ‘the end of history’ in the 1990s, where we can read ‘history’ in the Marxist way as specifically the history of class struggle, was somewhat premature: even allowing that democratization equalized political power, we are still far from a level playing field. Power needs to be decentralized not just along a single axis, but to analyze this, we first need to return to our initial question.

The Three Columns Of Power

The first way an elite can hold power over a greater ‘common’ population is by simply controlling the monopoly on violence: by having the means of punishing those that fail to fall in line. This is political power, and it is the most overt way of control, threatening direct harm (if not by physical means, via incarceration or other punitive measures) to those who would oppose it. As it is the most visible means of power, it is often mistaken for power as such: thus, democracy is seen as divesting the ultimate root of power to the subjects of the state, the people themselves. By these lights, the present situation must seem puzzling: up until fairly recently, the number of democracies in the world has been steadily increasing, while globally a small share of high earners has been amassing an ever bigger piece of the pie. If power resides with the many, why does the wealth distribution seem to favor the few?

The answer is, of course, that political power is not the only sort of power. Think back to our hypothetical billionaire in their bunker: while they may have a ‘police force’ to enforce their will on the rest of their subjects, the loyalty of that force must itself be ensured—for instance, by controlling access to resources, such as food and water, or goods needed to produce necessities for everyday life. Political power, thus, is supplanted by economic power: control over the means of production, in a word.

Power exists not just on a spectrum between ‘democratic’ or ‘autocratic’ rule, it also comprises an economic dimension in that economic resources can be more or less equally distributed. People need to feed themselves, they need clothes, shelter, and the resources necessary to procure, manufacture, and trade these items. Control access to these, and you can exert a great deal of control over the people.

While as a society, we have largely internalized the superiority of democracy over authoritarian forms of government, the workplace as the main locus of economic power is still run in a centralized form, with a monarchic CEO standing at the top and wielding near sovereign authority over the corporation. Just as it was unthinkable in the days of lords and kings that the people should wield the power, it is largely still unthinkable today that the workers should direct economic forces; but in the end, socialism is just the ideals of democracy applied to the forces of production. We should thus not accept uncritically the cries of those who stand to lose their power that ‘there is no alternative’.

Nor should we think that these two dimensions of power are independent. Deprivatization of the economy in the face of an insufficiently democratic distribution of political power just leads to Soviet-style state capitalism. If the authority over the means of production lies with the state, it must be first democratized, otherwise we are just trading one elite for another. That means we must interrogate the legitimacy of wielding economic power in just the same way we question political authority: why is it, for example, that we have long since decided that state rulership should not be heritable, while around 60% of billionaire wealth is derived from inheritance, cronyism, or abuse of monopolies?

But this still does not fully characterize power. What, after all, is to stop the weaponized arm of political power from rising up and seizing the resources for itself, installing itself in the prior power’s seat? Why, in other words, should the billionaire in their bunker not expect a coup at the earliest opportunity? The answer lies in the fact that it needs collective action to rise up against power, and it is the purpose of the third axis of power to disrupt any such action. It does so by giving us a story of how we, and only we, can ascend to power, if only we work to uphold the current order.

The Soteriological Dimension Of Power

The billionaires tell their subjects: “Work hard, and one day, you, too, can join our ranks. But watch out for those others, they seek to cheat you out of assuming your rightful place at the table and claim it for themselves!” In one fell swoop, two aims are served: first, people acquire an incentive to obey the rules and work for the system; second, they become suspicious of their compatriots and police them for any deviation on their side. That way, collective action becomes highly restricted: any individual stands to gain more by acting against the interest of the collective and outing any subversive activity to rid themselves of potential competitors and increase their chances of getting a larger piece of the pie.

Power thus has a soteriological dimension in that it intimates a narrative of salvation: if you do as you are told, you, too, can ascend beyond your station. But only the righteous can walk this path, so be weary of temptation, and avoid those who would seduce you to sin! Whether there is an overtly theological component, such as with kings and queens of God’s grace, or not, such as with the iconographic megalomania of the Soviet Union, is almost besides the point: whether the reward is in this world or the next one, what matters is that it is scarce and that it can only be attained by walking the narrow path of ideological purity. Meritocracy or prosperity gospel, what counts in the end is that we get what we deserve by the righteousness of our work, while they don’t take from us what they covet by the wickedness of their ways. Don’t worry about those billionaires shirking their taxes—with enough hard work, you can be as they are! But be mindful of the single mom on food stamps or the immigrant coming for your job, since they want to cheat you out of the reward that’s rightfully yours.

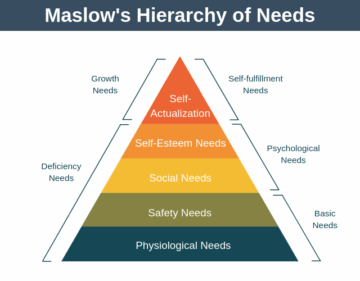

This identifies three main dimensions of power: the political, economical, and soteriological axes. Each of these provides a lever by which the few can imposition their will upon the many. We thus should strive towards a greater dispersal of the roots of power along each of these degrees of freedom: towards more democracy, more social market policies, and a more secularized narrative of salvation, or meaning. (I should perhaps note, here, that I am not arguing against religion as such, but rather, against religion and similar narratives as (ab-)used as a means of control, whether that is just voting for the right party or committing acts of terrorism against ‘enemies of God’. Therefore, I am using ‘secularization’ as a stand-in for a process in which whatever meaning-making narratives there may be are wrested away from centralized control.)

This is, by nature, a simplified first-order approximation kind of model of power. But I believe it holds a certain explanatory value. One immediate takeaway is the explanation of the collusion of the different columns of power once a ruling elite sees a threat to their rule. The levers don’t act independently, but form parts of a complex system of gears and pulleys to an end of mutual amplification of force. We see this, for instance, in the often noted alliance between industry and politics in (proto-)fascist societies. As Mussolini put it, “Fascism should more appropriately be called Corporatism because it is a merger of state and corporate power.” In a Marxist analysis, fascism is a reaction to capitalism in crisis, consolidating failing economic systems by means of political strongmanship. One example of such an—albeit failed—attempt is the 1933 Wall Street Putsch, where business leaders including members of the Morgan and DuPont families sought to overthrow president Roosevelt in the midst of his ‘New Deal’ program in the wake of the Great Depression. Fascism also involves a salvation narrative, where only the leader can lead you (as a member of the in-group) to your rightful destiny against the pernicious influence of them.

Fascism thus is the point where the political, economic and soteriological dimensions of power coalesce, often in the form of a single individual with ties to industry and politics that promises to lead their followers back to the greatness they are owed. It is where power takes refuge to consolidate itself against the influence of decentralizing movements. We tend to think of fascism as an outside evil, an alien parasite poisoning hearts and minds, but it is in fact internal to the logic of power, which finds its ultimate exposition within it. Hence, any effective resistance must be resistance against the tendency of power to accumulate along any of its axes. Democratization alone is not enough; nor is a socialized economy. Any claim of the few to direct the will of the many, if it is not merely an expression of this will, should be viewed with the utmost suspicion.

We are seeing today again a reaction to power being threatened: economic power with the 2008 global financial crisis, and authoritarian power with the democratization movements in the early 2010s of the color revolutions, the Arab spring, and perhaps most consequentially the Snow revolution in Russia, which has laid the groundwork for a decade of antidemocratic action on the part of the Putin regime. In many of these cases, power has moved towards consolidation as a result: increasing authoritarianism in the US where formally power was exerted mostly along economic lines, rising theocratic influences evinced both in Trump’s cozying up to the American religious right and in Putin’s weaponization of the Russian orthodox church, and technofeudalist dreams of ‘freedom cities’ where economic power reigns supreme. In the dynamics of power, the present day seems uniquely poised at a crossroads: are we witnessing a full swing of the pendulum back to ironclad control by a privileged few—or is what we’re seeing just the extinction burst of centralized power?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.