by Jonathan Kujawa

Mathematics is an inexhaustible subject. Every time you think you’ve mined out a vein, you hit a new gem. There is no clear reason why this should be true, but all evidence shows that it is mathematics all the way down [1].

Mathematics is an inexhaustible subject. Every time you think you’ve mined out a vein, you hit a new gem. There is no clear reason why this should be true, but all evidence shows that it is mathematics all the way down [1].

I once saw a talk by a mathematician near retirement who had made numerous influential discoveries over the years. The recurring theme of the talk was how, time after time, he finally understood everything about his favorite corner of mathematics. The joke, of course, was that each new discovery revealed how his previous “complete” understanding still overlooked interesting and important things.

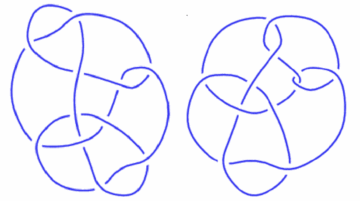

An excellent example of this phenomenon is knot theory. This is the mathematics of figuring out how to distinguish different knots. Two knots could look very different, but could turn out to be the same after some manipulation. Or not! For example, to the right are two knots created by Conway and by Kinoshita-Terasaka. It turns out to be extraordinarily difficult to figure out if they are the same knot or not.

This is one of those kinds of research that politicians and know-nothings love to sneer at. It sounds stupid, trivial, and of no use to anyone. However, if you’re one of those who care about real-world applications, the mathematics of knot theory plays a role in string theory, protein folding, quantum computing, and more.

But if you’re one of those who find math interesting for its own sake, then you’ll be glad to learn that knot theory is a rich vein of mathematics that continually reveals deep, beautiful, and interesting new discoveries. In this essay, I thought I’d share yet another new discovery in knot theory. Longtime readers of 3QD won’t be surprised: we’ve talked about knots many, many, many times over the years.

This time, it is a preprint by Dror Bar-Natan and Roland van der Veen. They released it a week ago, which makes it about as cutting-edge as you can get. They explain their current understanding of a new knot invariant. A knot invariant is something you can compute for a knot that helps you tell knots apart. Because knots are complicated, you want your knot invariant to be something comparatively simple. The trade-off is that sometimes different knots will have the same invariant.

To draw an analogy, if you wanted to create a human invariant, you might record each person’s height and eye color. The upside is that these are two simple pieces of data that are easy to keep track of. The downside is that it is an imperfect tool for distinguishing between people — lots and lots of people have the same height and eye color. Likewise, knot invariants are flawed tools for distinguishing between different knots.

One of the earliest knot invariants is the Alexander Polynomial. Each knot has an Alexander polynomial. This is a polynomial, similar to those seen in high school, with the added wrinkle that it is allowed to have both positive and negative exponents. For example, x2 – x + 1 – x-1 + x-2 is the Alexander polynomial of a knot. If you notice, the Alexander polynomial is unchanged if you replace every x with x-1, and vice versa. This symmetry is a hint that much deeper mathematics can be found if we keep digging around the Alexander polynomial.

Alexander introduced his polynomial in 1923. John Conway later found a way to compute it using something now known as a “skein relation” [2]. The idea is that it is very easy to untie a knot if you can pass the rope through itself. Now, of course, only a magician can pass a rope through itself. But if you could, you could interchange the top and bottom strands at any crossing you like and thereby eventually untie the knot (in math, we glue the ends of the rope together, so no knot means you have a circle):

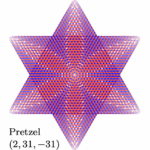

This brings us to the paper by Bar-Natan and van der Veen. They create a new invariant they call Θ. Since that’s the Greek letter Theta, that’s what I’ll call it. Their Theta invariant is a polynomial in two variables. For example, x – 1 – 2y +4x-1y-1 is the Theta invariant for a knot. Theta is computed in a manner reminiscent of the Alexander polynomial, but, not surprisingly, it is significantly more complicated. However, computers can calculate it quickly, and evidence suggests that it is very good at distinguishing between different knots.

Even better, Bar-Natan and van der Veen show that you can visualize their invariant in a beautiful way.

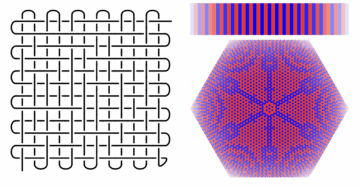

The Alexander polynomial could be recorded by writing down the list of numbers in front of each power of x. In turn, you could turn those numbers into colors and get a colorful “bar code” that visually represents the Alexander polynomial. In the same way, the numbers in front of the powers of x and y in the Theta invariant can be used to create a two-dimensional “QR code” (it’s two-dimensional because there are two variables).

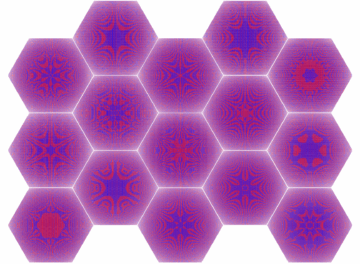

In the picture above, the barcode on the upper right depicts the Alexander polynomial, and the hexagonally shaped QR code depicts the Theta invariant. The left-right symmetry of the barcode is a visual illustration of the x ↔ x-1 symmetry of the Alexander polynomial. When you look at the hexagonal QR code, you can’t help but notice it also has symmetry. As further evidence that something is going on, consider this collection of hexagonal QR codes for some random knots with 300+ crossings:

For even more evidence, look at page 3 of their paper. There you will find dozens and dozens of knots along with their Alexander barcodes and Theta QR codes. Like here, you will see patterns that insist that there is something deeper going on.

However, we’re at the cutting edge of human knowledge. And here at the edge, we are able to see things with our mathematical third eye that aren’t yet quite in reach. In this case, Bar-Natan and van der Veen conjecture that their Theta invariant has the symmetry these pictures suggest. But it’s currently only a conjecture. It might be true, it might be false. It sure looks true, but believing in things you want to be true is the stuff of conspiracy theorists.

Bar-Natan and van der Veen give numerous other conjectures, observations, speculations, and dreams about their Theta invariant. For example, they note the striking similarity of their QR codes with the images generated by the Chladni plates that we discussed last time here at 3QD. While they can’t yet formulate a precise conjecture, they don’t think this is a coincidence.

Bar-Natan and van der Veen have struck a rich vein of mathematical gold. It will keep them and other researchers busy digging for years to come. If you’d like to help, they provide Mathematica code that lets you compute the Theta invariant at home. You’re invited to help generate more data to support (or contradict!) their conjectures.

[0] Title borrowed from Emily Dickinson. All uncredited images are from the paper of Bar-Natan and van der Veen.

[1] It’s turtles all the way down:

“If your theory is correct, madam,” he asked, “what does this turtle stand on?”

“You’re a very clever man, Mr. James, and that’s a very good question,” replied the little old lady, “but I have an answer to it. And it’s this: The first turtle stands on the back of a second, far larger, turtle, who stands directly under him.”

“But what does this second turtle stand on?” persisted James patiently.

To this, the little old lady crowed triumphantly,

“It’s no use, Mr. James—it’s turtles all the way down.”

[2] In writing this essay, I learned that Alexander also had a formula for his knot using a skein relation, but it was buried in the back of his paper and forgotten for many years.

[4] A small technical point. In the video, they use a different variable than I’m using. Replace each t1/2 with x to get the Alexander polynomial I’m talking about.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.