by Thomas Fernandes

A rodent with orange teeth and a paddle tail comes across a river. He tries to build a lodge but the stream is too low so he grunts, “Dam!”.

While the pun captures the beaver in miniature, the real story lies in the web of relationships that shapes it and the ecosystem in return. To see how deeply a species is shaped by these relationships, it helps to look first at its body.

This 20 kg semi-aquatic mammal is an extraordinary swimmer. It uses its tail as a rudder and webbed hind feet to glide efficiently through water. It can hold its breath for up to fifteen minutes thanks to a suite of cardiovascular adjustments known as the diving reflex. This reflex slows the heart and redirects blood flow to vital organs, a trait shared with seals and penguins.

Their fur is equally adapted: a very soft underlayer traps air and provides insulation with an incredibly high hair density (ten times the density of human hair), while a covering layer of longer guard hairs repels water, a property further enhanced by oil secretions that act like wax. Even their eyes are specialized for underwater vision, equipped with a nictitating membrane (a third transparent eyelid) that functions as natural goggles underwater.

By observing their bodies, it would be tempting to think nutria are close relatives. After all, they share water-repellent fur, webbed feet and even a diving reflex.

But looks can be deceiving: beavers and nutria split from a common ancestor 50–60 million years ago, long before humans and chimps parted ways just 7 million years ago. This is a case of convergent evolution, showing that similar environmental pressures can produce similar forms even in lineages with very different histories. Yet such adaptations are always built on top of existing genetic heritage. To understand what truly set beavers apart, we need to turn away from look-alikes and toward their real cousins in the desert. The closest living relatives of beavers are North American desert-dwelling burrowers. Examples include kangaroo mice and pocket mice. Despite their vastly different appearances, observing their behavior reveals deep evolutionary continuity.

Kangaroo mice use their teeth to husk seeds. Beavers’ continuously growing incisors cut wood and strip bark to feed on the nutrient-rich cambium beneath. In northern climates grasses often contain silica that will erode and abrade softer enamel. As a result, many rodents evolved iron-rich enamel on the exterior giving them their characteristic orange color. Beavers have the hardest enamel among rodents, twice as hard as human teeth. They are also self-sharpening thanks to a softer interior that erodes faster from gnawing, creating a razor edge, ideally suited to cutting through woody trees.

Pocket mice store food seasonally. Kangaroo mice take this further: they larder hoard, keeping a central cache of seeds, and also store fat in their tails. These adaptations, first evolved to handle desert scarcity, now help beavers survive the winter. During summer beavers will store an underwater cache of small branches and sap near their lodge that they can access easily without even surfacing. In addition, the beaver’s tail is fat-filled, a distinctive energy reserve for winter, echoing ancestral strategies.

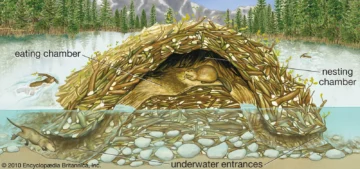

Kangaroo mice burrow for heat protection and predator evasion, and pocket mice excavate complex tunnels with many entrances. Over millions of years, this ancestral strategy of refuge set the stage for a remarkable transformation: some descendants became aquatic engineers. Initially soft soils along riverbanks provided the best sites for burrows, stabilized by roots, while water access offered both predator evasion and abundant nearby resources. Even today some beavers will dig their lodge in the riverbanks. But suitable sites are scarce, with only a few offering firm soil and water deep enough to protect entrances from freezing in winter. The ability to construct lodges increased both the quality of burrows and the number of viable nesting sites. By modifying water flow, beavers could further improve site suitability.

Today, triggered by the sound of rushing water, beavers build and maintain dams. Beavers stand on their hind legs, using their tails for balance, gnawing through smaller trunks in minutes. Larger trees, sometimes up to a meter in diameter, require weeks of persistent effort. Once down, the trunks are broken into transportable sections, dragged or floated to the lodge or dam site. This laborious process demands persistence and energy. There, beavers anchor branches into muddy stream bed to create a sturdy foundation. They then weave sticks, bark, mud, and rocks layer by layer. Vegetation is added next, forming a superstructure that retains water, sometimes extending up to 700 m in length. They build smaller lodges for rest and winter, featuring multiple submerged entrances and air conduits for ventilation. When water already submerges the lodge entrance (roughly a meter deep), dam-building is unnecessary. The main goal of protection from predators and ice formation is already achieved. Such adaptation also coevolved with social changes.

The high labor investment for building and maintaining lodges, coupled with harsh winters and limited, patchy sites, favored cooperation. Under these demanding conditions, young beavers remain dependent on their parents for survival. Consequently, pair bonding and cooperative behaviors evolved in an otherwise solitary lineage. Pairs remain bonded for life, raising their offspring, typically four to eight per year, and they remain with their parents until about two years old, when they disperse to establish new lodges. Evolution didn’t invent new tricks; it rewired the old. The claws that once carved dry tunnels now shape lodges, dams, and canals. Teeth once made for gnawing roots became chisels to fell trees. In a single lineage, a solitary desert-dwelling burrower became a cooperative wetland architect. This transformation rippled outward, reshaping streams, ponds, and the entire web of life they support.

By building dams and lodges, beavers slow streams and create ponds, which trap sediments and allow organic matter to accumulate. These ponds foster microbial communities that recycle nutrients and purify the water, supporting abundant aquatic invertebrates. Mollusks find shelter, worms benefit from nutrient-rich soil, and dragonflies thrive in the still water. Fish and amphibians follow. They attract birds and other predators, ultimately boosting overall biodiversity. Trees felled by beavers, typically species like willows, alders, and poplars, coppice and regrow from stumps. Although initially costly for the trees they benefit from increased light, nutrient-rich soils, and protection from flooding. Downstream, water flow and sediment patterns are altered in complex ways. Slower flows can reduce erosion and help maintain water levels during dry periods, but sediments and nutrients trapped behind the dams may limit what reaches downstream plants and fish. Beaver activity thus cascades through wetlands, transforming hydrology, vegetation, and food webs. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, wetlands cover only 6% of the Earth’s land surface but support 40% of all plant and animal species.

Behavior and physiology co-evolve in relation to the environment, and a species’ ecological impact emerges only in context. Beaver populations once faced near extinction due to fur and castor gland hunting. In 1946, twenty beavers were introduced into Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, in hopes of establishing a fur trade. The climate resembled Canada’s, and the beavers behaved as usual, building dams and lodges. Trees like willows are highly adapted to life with beavers. They can regenerate after being cut via root suckering. Dormant buds, combined with sufficient stored energy and nutrients, fuel new growth when needed. Specialized aerenchyma cells transport oxygen to the roots, keeping them alive even underwater. Local southern beeches, in contrast, lack dormant buds and cannot survive prolonged root submersion. When the beaver dams flooded the area, over 80% of these trees died within a decade. From the pond itself mollusks, worms, trout, and some birds benefited, while forest species declined drastically. The inundated land consisted of millennia old peat rich in stored organic matter. Flooding altered oxygen availability and destabilized the peat. This destabilization triggered successive releases of methane while submerged, followed by carbon dioxide as the peat dried. With almost no predators, the beaver population exploded, reaching hundreds of thousands of individuals, amplifying the disruption caused in this ancient ecosystem. Focusing solely on the individual organism misses the larger picture: ecosystems are not merely collections of beings but a choreography of relationships.

As we’ve seen with beavers, every trait reflects a history of interactions with the environment and other species. Each adaptation carries the imprint of these relationships, shaping how the organism moves, feeds, and influences the web of life around it. Each link in this web is a doorway into the ecosystem, and energy powers every action and sets limits on what is possible. Captured, produced, or stored, it moves through the web, linking organisms and shaping ecosystems. The next essay will explore predator-prey interactions and show how these connections influence life far beyond a simple kill or be killed view.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.