by Kevin Lively

Introduction

It is a well-worn observation that a sense of fatalism seems to be settling across the peoples of the world. There is a wide-spread feeling that global developments are echoing trends from the 1930s. Economic centers in the USA are gearing up their domestic industrial capacity, while the defense department speaks of Great Power Competition. China does the same, while trenches and mines scar the fields of Ukraine. With the NATO alliance under question, Europe begins to look after its own industrial base while refugees from drought-stricken, strife-torn lands drown in the Mediterranean. Those who manage a safe arrival, both in Italy as in Texas, often struggle to integrate into an aging society despite a desperate need for young workers. Substantial and growing fractions of the US and European populations are of the mind that this influx of hands — ready and eager to work — should not be turned to repairing crumbling bridges or staffing overworked retirement homes. Rather they should be banished and sent away in disgrace, regardless of the final destination.

An unspoken thought seems to be flowing among the currents beneath many people’s minds. More and more often now, it seems to break to the surface at unexpected times. Here’s a drinking game: every time you hear some variation of the phrase “in today’s geopolitical climate”, take a shot. Depending on where you work and what topics your lunch conversations drift towards, it may be unwise to play this game on a weekday. These events increasingly beg for certain pressing questions to be asked.

For example: how do we, as a species, deal with these dislocations of people, and the disruptions to their means of supporting themselves? How do we, as a species, plan for the future dislocations to come, as crop cycles grow increasingly unpredictable and failure-prone, while the ocean’s fish are replaced with plastic as ever more forms of pollution with unknown consequences accumulates? How do we, as a species, allocate this planet’s apparently dwindling resources between ourselves in order support a simple life of dignity and peace, unburdened by the deprivation of extreme poverty and the chaos it brings?

Discussions around such questions are, by necessity, discussions of death, religion, power and land — among the topics best avoided both at Thanksgiving and a bar. Thus there is a tendency to tread carefully around them while in polite company. Yet in today’s geopolitical climate it increasingly behooves us all to address such questions in a sober and critical manner. Ideally we should all have some mutually understood context for the stage on which these events are playing out, whether we’re in the audience, on the gantry or elsewhere, busy prepping the smoking lounge in your bunker.

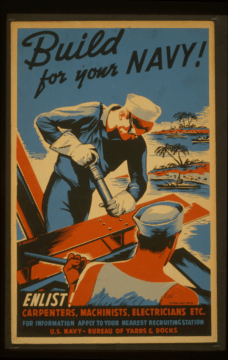

In my last article I sketched out the temptation of military expenditure as a first-line policy to address economic and social upheaval from the perspective of many Americans who came of age around WWII. Given that Europe, China, the United States and Russia seem to be simultaneously pursuing this same policy to various degrees, and that previous examples of rapidly arming power centers did not end well, now is a pertinent juncture to asses how the reasoning behind this can evolve under domestic-political and external-security stressors.

In this article I will attempt to frame some examples this line of macroeconomic reasoning using the cases of modern Germany and the USA in the early Cold War. I will try to highlight some of the dynamics which can occur when there is political willpower to use heavy government investment to address security and economic concerns simultaneously. Broadly calling this type of policy Military-Keynesianism, I will compare the confluence of domestic and external forces which in the case of the United States, came together to lock the USA into what some analysts refer to as a permanent war-time economy for much of the 20th century.

My goal in this exercise is to attempt to build a common understanding of the factors which are considered in the halls of power when the outside world appears consumed by chaos. At the same time we can gain a better insight into the choices which led to the so-called Pax Americana, the hegemony of the USA over Western European and East Asian affairs, which is rapidly changing at present. In my next article I will discuss this later topic and how Western Europe fits into it in some more detail.

Guns and Butter

In today’s geopolitical climate a belief which has been long held in the USA is flourishing; we can hit two birds with one stone by providing security and jobs with military spending. This belief is now rooting deeper into the European mentality, with some variations which may be interesting to an American audience. Germany’s new government announced as part of its coalition contract that it would create exceptions to constitutionally mandated balanced budgets in order to boost military spending. However, in the same stroke the Merz government allocated €500 billion for modernizing domestic infrastructure — and up to €1 trillion overall. This number of €1 trillion should be compared to a GDP of about €4 trillion and a current rate of government-spending-to-GDP of 49.5%.

Beyond the price tag this development is remarkable because, in the previous incarnation of this center-left (SPD) and center-right (CDU) coalition, led by the conservatives, they stuck to balanced budgets despite the economic turmoil in Europe throughout their tenure from 2013 into year one of the pandemic. It appears however that the successive shocks of Corona, Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine, the subsequent choking off of Russian resources to Germany’s industrial-export oriented economy, and Trump’s undermining of NATO have utterly annihilated fiscal austerity as a viable political strategy. The business party FDP, responsible for the balanced budget law being passed in 2009, broke out of the previous government coalition and in the last election fell below the minimum vote quota required for participation in the legislature. Now Germany is increasingly committed to further massive government investments, despite government budgets flipping from net positive to net negative.

Such a blend of military and domestic investment is of course a standard macroeconomic strategy in the post war world. This is just a shift in positioning on the x-y plane of Guns versus Butter, investing simultaneously in both the welfare of the nation and the state’s capacity for warfare. For the purposes of this discussion I will frame the macroeconomic strategy of Keynesianism as broadly referring to the butter axis, namely investments in socially useful forms of investment like schools, healthcare and social security. When including the guns axis by increasing the fraction of the stimulus directed towards military investment, I will refer to the model using both policy dimensions as Military-Keynesianism. These axes are not mutually exclusive, and motion in these two dimensions depends on the political willpower capable of mobilizing money to push the economy in a given direction.

Germany at the moment provides us with an apt example of a power center, in this case the industrial heartland of Europe, grappling with the guns and butter debate in the context of rapidly changing security concerns. We can already begin seeing the dynamics which take place when a critical mass of political will is achieved in such a climate. Take for example the recent surprise announcement by the CDU foreign minister that military spending targets were abruptly jumping from 2% to 5% of GDP — a difference of about €120 billion. This statement apparently took some SPD members of the coalition by surprise. One anonymous SPD member was reported as saying that the new number was “not conceptually underpinned”. The stocks of Rheinmetall, the German arms manufacturer, reacted positively, as one could expect.

This brings us around to the central question of Military-Keynesianism: how much butter and how many guns? Even this framing raises its own questions. How cleanly can we even separate the two axes? Defense workers need cars and houses and haircuts and the like, so surely the money is flowing through society, even if its delivered from an artillery gun?

The Elysian Markets

Even if the hardware products of military spending are not necessarily productive for society outside of an active war of defense, during peacetime it is often seen as an employment program. However this program has a significant difference to other forms of domestic spending: it caters to a seemingly endless market. There’s only so much room in the global civilian marketplace for advanced manufactured goods, as China is busily showing everyone by seemingly saturating global auto markets. This is of course a central aspect of many markets, as seen by the Agricultural Adjustment Act purchasing and deliberately rendering surplus agricultural products unusable in order to drive prices back up to profitable levels during the Great Depression. These policies led, for example, to the slaughtering of up to 6.4 million hogs at the cost of $31 million just to raise the price of pork so that people would continue producing it. Keep in mind that this was happening while the dust bowl was causing starvation conditions in some parts of the country. These kinds of market interventions, even if they provide a net benefit by some metrics, are obviously controversial, and thus cost a lot of political capital to maintain.

In contrast to agricultural or civilian production, the military economy can absorb more investment on a more frequent basis, as weapons systems require constant upkeep and improvement, yet quickly become outdated regardless. This essentially functions as a nationwide industrial-systems subscription service. If your subscription is significantly out of date it becomes a political liability, presenting an easy line of attack for domestic war hawks who then characterize the incumbent government as being reckless and weak. US political history is of course rife with this strategy, such as with the Sputnik crisis and (in actuality baseless) bomber and missile gap scandals. Then, god forbid, if the hardware is actually used to kill human beings, by that point at the very latest it will certainly need to be replaced, since you probably didn’t kill everyone you were aiming at, and the survivors may not be in the mood to talk anymore.

What makes this seemingly bottomless market even more attractive from the perspective of central policy planners is that the labor pool required to staff it must have competency across a diverse range of highly technical skills. Logistics, advanced manufacturing, computing, materials science, exponential data scaling, biomedical research, the list goes on. It’s hardly a controversial statement to simply observe that nearly every form of high technology infrastructure existing today, from pressurized airplanes to commercial satellite networks and the internet, has had some degree of military investment in its history of research, development and deployment.

Those of us who are of a pacifistic nature will naturally recoil at the implications which may be extrapolated from this observation. Under cautious analysis, one can see that the conclusions one reaches are strongly dependent on the assumptions taken with regards human nature. For example if you are of a Hobbesian mindset and believe that “the condition of man [in a state of nature] … is a condition war of everyone against everyone”, and that therefore, only a powerful sovereign or hegemonic power can ensure peace, then you may see no reason to hesitate on investing heavily in the dimension of guns. Indeed if you are a true believer then it can even seem morally necessary to hone your capacity for violence in order to effect what you want to see done in the world. Examples, potentially, include how foreign interventions such as George H. W. Bush’s in Iraq are often framed in terms of stopping another Hitler.

Operating under the morally fatalistic assumption that mankind is irrevocably banished from the Garden of Eden, one can then proceed with the following hypothesis to frame the previous observation: that military production is necessary, or at least quite beneficent to developing a modern economy. Regardless of the truth value of that statement, it does clearly help to maintain a high level of employment. As debates over drug or housing policy will show you, such a simple chain of cause and effect is rarely agreed upon in the social or political sciences. Thus, this tool has been used by statesmen around the world from Kim Jong Un to John F. Kennedy. In broad strokes this is also roughly the policy pursued by both Nazi Germany, Russia and Japan leading up to 1939. Nazi rearmament was used to recover its industrial economy after the economic collapse of the Weimar republic while the USSR transitioned from a backwards agricultural society into to space-faring one in the span of 40 years. Japan meanwhile went from being an essentially medieval society to holding its own imperial sphere of influence in East Asia standing on par with the European Great Powers. One need hardly say that all of these examples are rotten throughout with atrocities.

The negative effects of military surpluses is something less obviously present in the case of ostensible democracies, so long as one avoids impolite questions on how the colonies were governed, or why the local police have tanks. Regardless of the ideological framework, for the share of the domestic population which is not a direct target for varying degrees of state violence, ethical qualms which may arise from building exclusively for the purpose of killing one’s fellow man are swiftly ameliorated. We are constantly inundated with assurances that this is necessary for our own security. Alternatively, for crusaders among us, we are told that our culture embodies a higher calling whether it be ensuring the world is safe for Democracy, Communism or the master race.

If however, we start from the premise that not everyone is a bastard, and that most people would rather live in peace with their neighbors than in open conflict against them, if we instead assert that gold spattered with the blood of our brothers is not worth its weight, if, instead, we take a moment to study the question of whether $4 million is better spent on one tank or on an elementary school, then where does that leave us?

The danger of rearmament is that once every power center begins doing so, it develops an inescapable self-consistent logic: “If we don’t build it, they will”. Once more of the domestic economic activity begins to rely on the industrial investment, it becomes a political end unto itself. Eventually, as with the pigs, the surplus needs to go somewhere.

In my next article I will discuss a perspective of how this story played out in the US decision to rearm after WWII in the context of the domestic and international environments of time. Using the declassified record I will explore how the planners charged with maximizing the security and benefit of the United States viewed the situation, and how the global economic and military superstructure of the next half century began to coalesce, from which we can maybe see the contours of what will come next.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.