by Jerry Cayford

I listened some weeks ago to a terrific discussion between Ezra Klein and Fareed Zakaria. And it really was terrific. They were both at the top of their game, doing a certain thing at a very high level. Still, I have a slight bias against both these guys, and complicated feelings about what they do so well. My pleasure in their intelligence was tinged with frustration that they aren’t better, and with a slight melancholy about the path not taken. Critique mixed with autobiography. I was supposed to be them.

I knew early on that my father did not aspire for me to be president, like other boys’ fathers did, but rather to be the president’s closest adviser. I was supposed to grow up to be McGeorge Bundy—to pick a name from when I was first imbibing this career plan—I was supposed to become Jake Sullivan, to pick someone recent. And if I did not make it quite that close to the seat of power, well, I was still supposed to be Ezra Klein or Fareed Zakaria or some other talented policy analyst, saving the world through the practice of intellectual excellence.

What Klein and Zakaria practice are “the critical and analytical skills so prized in America’s professional class,” to use a phrase from an article of a couple decades ago unearthed by Heather Cox Richardson—another excellent practitioner—about the Bush administration’s replacement of critical and analytical skills with faith and gut instinct. Richardson recalls a passage from that article strikingly suggestive of Donald Trump’s current administration:

These days, I keep coming back to the quotation recorded by journalist Ron Suskind in a New York Times Magazine article in 2004. A senior advisor to President George W. Bush told Suskind that people like Suskind lived in “the reality-based community”: they believed people could find solutions based on their observations and careful study of discernible reality. But, the aide continued, such a worldview was obsolete. “That’s not the way the world really works anymore…. We are an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors…and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

In our era of conspiracy theories, fake news, and relentless lies, this rejection of the “reality-based community” sounds like a conservative confession of contempt for truth. It is easy to mock, and both Suskind and Richardson don’t hold back.

And yet, beneath the Bush official’s unfortunate phrasing is a point that is basically right. It is a claim about “the way the world really works”—plainly, then, it is not actually rejecting truth or reality —and it is worth some thought at this moment when Democrats’ critical and analytical skills are floundering before an onslaught of Republican actions.

If I need a highbrow warrant for taking seriously some smug official’s insistence that action trumps critical thinking, I can cite Wittgenstein’s fondness for Goethe’s line “Im Anfang war die Tat”: In the beginning was the act. But I have a more down-to-earth example, one with a personal connection. The mathematician Ed Thorp figured out how to count cards in blackjack to tip the odds in the player’s favor. You’re probably familiar with his system, either from general knowledge of card counting or from the movie “Rain Man,” with Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman. Thorp and my father were math grad students together at UCLA in the 1950s, and my father long ago told me this story.

By rigorously playing Thorp’s blackjack system, a player is mathematically guaranteed to win, given a statistically large enough number of hands. After plenty of testing, Thorp went off to Las Vegas to try his system out, and he promptly lost a bunch of money. Puzzled, he checked and rechecked his calculations and consulted colleagues on how this impossible result was possible. As you may have guessed, the casino had spotted him counting cards and assigned him a dealer who cheated. The rules of blackjack did not constrain the casino. Thorp’s solution was to get a professional gambler to do the playing and avoid cheating dealers (change tables, change casinos), and thereafter they won consistently, as mathematically predicted.

In this story, Thorp employs the analytical skills of “the reality-based community” to “find solutions based on…careful study,” but then runs up against “the way the world really works.” While Thorp was studying—and figuring out how to beat—the reality that the casino had created, the casino would “act again, creating other new realities” (by cheating). The Bush aide’s point applies not only to empires but to the most ordinary situations; situations change—actors change them—and key assumptions that inform critical analysis may no longer apply.

Whose reality is real, then, the analyst’s or the casino’s? Obviously, both of them. But the two are—as we might put it—playing different games. Yes, they are both playing the game of blackjack (against each other), but one’s game is blackjack in the context of analyzing probabilities and the other’s is blackjack in running a business. The crucial difference is that the mathematician’s analysis applies only within a well-defined set of rules, assumptions, definitions, etc., whereas the casino’s game is essentially open-ended.

To his credit, Ed Thorp adapted to the way the world really works, and sought out and employed other skills suitable to the casino’s rule-free game. Hijinks ensued, Ed wore disguises, casinos drugged his coffee, all in good fun, of course. Over time, Ed won many thousands of dollars playing blackjack in Las Vegas, and casinos now take measures to discourage card-counting. Fidelity requires me to say, having now read Thorp telling his own story, that I think my father’s version may be a mashup of a 1958 Vegas trip, when Thorp lost money playing someone else’s faulty system, and 1961 trips—bankrolled by a professional gambler who approached Thorp after his 1959 paper—when Thorp’s own superior system led casinos to try various dirty tricks. After all, casinos did not know until after Thorp started winning that card counting was something they needed to guard against. What I like in my father’s version, though, is the clear moment when Ed is losing to the cheating casino: that baffling, frustrating moment when solid analysis encounters the way the world really works.

I see that moment everywhere in politics today. A notably similar incident was the disastrous testimony before Congress of the presidents of Harvard, Penn, and MIT. Helpless before the charge of failing to stop students calling for genocide of the Jews—a rhetorical tactic no more sophisticated or honest than the old chestnut “Have you stopped beating your wife, Senator?”—the college presidents apparently did not understand what the real game was. Like playing blackjack by the rules, they defended the appropriateness of narrow administrative actions; the real game, though, was a propaganda assault on universities as incubators of radical leftist genocidal antisemites.

More recently, Trump has been attacking big law firms, which are faring no better than the college presidents. The whole thing baffles most of us in the public. My father is interested in law (my late stepmother was a judge), so I sent him a podcast explaining how several big law firms are now the main power centers of the Democratic Party (“The Business of Big Law”). He responded, “I am impressed that big law and the Democrats are integrated. But if big law is so good, why are the Democrats so incompetent?” It’s a very sensible question, since top lawyers have replaced rocket scientists as society’s icons of brilliance (ones more attuned to our times: less nerd, more predator). I am trying to ask here a larger version of that question—there is a larger dysfunction than incompetence.

I do not mean to understate the incompetence. Like many, I followed closely the obliteration of Joe Biden’s agenda: Josh Gottheimer and the centrists stalling the Build Back Better bill, trying to run out the session; Chuck Schumer’s secret deal with Joe Manchin to delay BBB until October 1 in exchange for Manchin’s promise to allow a $1.5 trillion bill; then Schumer and Biden squandering Manchin’s promise by pushing for $1.75 trillion long enough for Manchin to renege safely; and then the afterlife of this fiasco (which I’ll touch on below). But there are only so many times you can blame systemic failure on individual incompetence. OMG, the presidents of our best colleges are idiots! OMG, the country’s top lawyers are idiots! OMG, Schumer and Biden are idiots! Eventually, we have to suspect some deeper problem, some defect common to the way all these obviously smart people think. And if you step back and look at the whole mess we’re in, you have to wonder why the critical and analytical skills so prized in America’s professional class (as Suskind puts it) aren’t working better. That’s my larger question.

***

The blackjack story highlights the clear line between what is inside Thorp’s mathematical analysis (the rules of the card game) and outside the analysis (casino shenanigans and Thorp countermeasures). Analysis only yields concrete results inside its carefully defined structure (objects of study, definitions, methods, etc.) Yet professional culture minimizes attention to that line. Part of professionals prizing analytical skills is captured by the slogan “Do the work.” The idea is that if you stay focused on your analysis and do excellent work within the norms and boundaries of your specialization, the rest will take care of itself: recognition, professional success, and the achievement of your goals will follow naturally. Internalize those norms and boundaries! This may be good career advice (good advice that I just didn’t take), but norms are artificial constructs, not natural ones, and the world outside of clear boundaries and agreed upon structure (e.g. at a casino) often works very differently from inside.

Suskind heaps scorn on Bush for neglecting the analytical skills Bush presumably learned in the Harvard MBA program. He quotes Senator Joe Biden’s assessment that neglecting those skills has not “served [Bush] well for the moment he’s in now as president.” Richardson, likewise, ridicules the Trump administration for believing it can bully into submission not only federal agencies but the press, the public, the judiciary, the truth, and “reality itself.” In other words, Suskind, Biden, and Richardson all take for granted that these skills are essential for successful functioning in the world. Their scorn feels to me like saying to the casino, “Ha! You can’t even beat me at blackjack without cheating!” They seem unaware that politics is largely outside the orderly boundaries of analysis. And it all reminds me of why I chose not to be a Klein, Zakaria, or Richardson.

It was when I was working for a policy research firm in Los Angeles that I veered off my ordained career path. The firm was called “Pan Heuristics,” and I worked there from 1983 to 1986. Pan Heuristics was every bit as arrogant as the name suggests, possibly deservedly so. It was a small but enormously influential firm—a dozen or so researchers (most of them formerly with RAND Corporation), four research assistants (including me), and a couple of support staff—under the leadership of Albert Wohlstetter and his wife, Roberta. Albert was the teacher or mentor to Paul Wolfowitz, Elliot Abrams, Richard Perle, and other neoconservatives (some of whom had worked for us). The thumbnail summary I heard was that four men dominated American military and foreign policy from the 1950s through the 1980s: Albert Wohlstetter, Henry Kissinger, Harold Brown, and a fourth whose name I can’t recall because, like Albert, he never accepted public office. Wikipedia says Albert was one of the people on whom Stanley Kubrick based the composite character of Dr. Strangelove (though I had never heard that). I have always thought that Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI)—the space-based missile defense program known popularly as “Star Wars”—was a Pan Heuristics brainchild; missile defense had long been our thing, Reagan had been our guy since he was California governor, and SDI caught the Washington establishment by surprise when Reagan announced it shortly after arrival there in 1981. But that information was classified above my level.

I was ideologically at odds with my conservative colleagues. And what that taught me was a watchfulness for caveats and complexities in those vaunted critical and analytical skills that I was raised to practice. My colleagues at Pan were indisputably excellent practitioners, yet I sometimes found their analyses subtly off target. For example, I had come to suspect that these committed cold warriors viewed the world through a black and white, US-versus-USSR lens partly because two-person, zero-sum games are just easier to analyze and solve than are the shifting realities of a multi-polar world. That is, the practice of professional analysis produces incentives to artificially simplify the analysis to make it easier and its results more definitive. There is a dangerous have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too character to doing rigorous analysis of strictly defined and bounded questions and then extrapolating straight out to the unbounded and messy world. You might lose a lot of money at the blackjack table. Or start a destructive war.

Listening to the Klein and Zakaria interview on foreign policy reminded me of the clean, rational arguments of those Pan Heuristics days. (And to repeat, the interview is genuinely smart and insightful.) Ironically, I believed Biden and Netanyahu had been in a real two-person, zero-sum game: whoever went to election first would lose, and whichever one was left would win reelection. (It wasn’t really zero-sum because thousands of Palestinian lives were at stake.) In the event, the game was called for personal indisposition, but I wondered if the smart professional analysts around Biden told him bluntly: to win your own reelection you must force an Israeli election, which Netanyahu will do anything to prevent. More recently, those clean, rational arguments have encountered the chaos individual actors can introduce. When I was at Pan, El Salvador was at the height of its civil war and death squads. American involvement there was one of our ugliest episodes, but I haven’t thought much about the country since then. Suddenly last week, the president of El Salvador shows up at the White House, just to prove he can come without bringing the wrongly-deported immigrant the Supreme Court ordered brought back. He’s come to tell Trump, if you want to defy your Supreme Court, I’m your man. You want to disappear inconvenient people? Your own citizens? Political enemies, maybe? I’m your man! It wasn’t completely unpredictable—nothing is—but it’s a jarring contrast to orderly analysis.

My concern is how analytical skills are actually practiced. That’s my concern about our politics now, and it was also my concern while working at Pan Heuristics and deciding on my career path. With an interest in policy and a double major in philosophy and economics, the natural directions were either law school, where many philosophy majors go, or a PhD in economics, which most of my work colleagues had or were pursuing. The policy world, though, was full of lawyers and economists, and I had misgivings about these likely paths due to my suspicions about analytical thinking among the professional class. At the same time, I also saw that rigorous analysis pursued with integrity could overcome biases and expectations. My boss Brian Chow and I did a deep dive into the costs and practicalities of space-based missile defense. We proved that the smart weapons a space defense required could be shot down with much cheaper dumb weapons, leading to an unwinnable arms race. Brian wrote me some years after I left the firm to say that our paper played a big role in killing the Strategic Defense Initiative, regardless of whether it was originally Albert’s baby.

In the end, I did not go to law school or into economics. Much to my work colleagues’ horror, I decided to get a PhD in philosophy. I thought the public policy world was lacking the omnivorous appetite for diverse methodologies characteristic of philosophy. The policy world, as it turned out, did not agree with me (mostly), but I was not to find that out until years later.

***

When I arrived at grad school, I was asked at the first social gathering the burning philosophy question of the day: does philosophy have its own subject matter? Having been out of college for some years (and never that socially plugged in), I was unaware of this debate. I thought a moment, and replied, “No, I don’t think so.” I could see from the reaction that I’d given the wrong answer. The question was shorthand for the idea that, since we philosophers are serious professionals, of course we have a subject matter, but philosophy is hard to explain to non-philosophers, so how exactly should we articulate our subject? Right away I’d encountered the pull on philosophy of the very inclination I thought philosophy cured. Philosophers, too, were longing to be specialists.

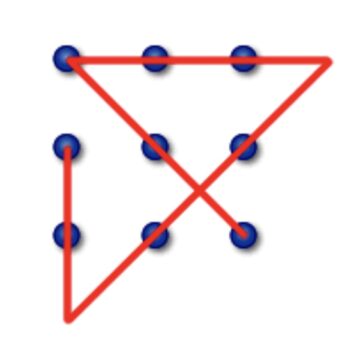

I’ve always thought of philosophy with a visual image: a piece of paper depicts human knowledge; circles on the paper mark the boundaries of disciplines, some overlapping, some discrete; philosophy is the paper. The disciplines, then, are the parts of philosophy—as science used to be “natural philosophy”—that have developed a subject matter and methodology substantial enough for people to become specialists and stop working outside their own bounded field. Philosophy, though, concerned the paper as a whole: why (and whether) a given issue was best addressed by the methodology of this circle or that one; what relations were among the disciplines and whether some were poaching the subject matter or corrupting the methods of others; and everything else not enclosed in a specialty. Where the disciplines had boundaries and specialized subjects, philosophy was the quintessential generalist study, born in wonder, home of the big picture and boundless curiosity.

There can be no general rule for setting the boundaries of an issue; the world is all one, and boundaries are created for practical purposes. Every thesis advisor tells every student, “Narrow your topic,” and it’s good advice. The fixed boundaries and narrow focus of analytical thinking are necessary to nailing down a substantive result. Nevertheless, someone has to watch where that result falls in the wider world. To revisit the fiasco mentioned above, for instance, after the centrists killed Build Back Better, they eventually allowed the Inflation Reduction Act, a bill half the size of Manchin’s original commitment. Smaller than it should have been, it was still huge, and it contained a big commitment to reducing carbon emissions. But two years later, approaching the 2024 election, implementation was stalled, construction of EV charging stations was close to nonexistent, and voters were unimpressed or worse. And now the Trump EPA is trying to claw that money back. It’s easy to say, “Incompetence” once again, but that’s not quite right. The drive for implementation petered out once the bill was passed. The problem was thinking that the game was passing a bill—a bounded, well-defined task, like playing blackjack, a task to which professionals can bring their analytical skills—while the real game was enrolling the citizens in a transportation revolution, solving climate change, winning the future, all goals of an unbounded, ill-defined project.

Even in philosophy, then, there is a pull toward thinking small. Still, a history of respect for the grand vision does retain force. My discovery of Wittgenstein was a shock and a revelation. Here was an astonishingly fearless, profound, and unconstrained thinker. I decided to write my dissertation on him. Meredith Williams, the Wittgenstein scholar, gave me a list of twenty books of secondary literature I had to read to get up to speed. So, I read book after depressing book, each working hard to domesticate Wittgenstein and blunt his originality; I did a twenty-book master class in using critical and analytical skills to squash disturbing and radical insights down into docile convention. But then I found David Bloor. A dozen pages into Wittgenstein: A Social Theory of Knowledge, I knew that Bloor understood Wittgenstein’s significance. Head of the Science Studies Unit at the University of Edinburgh, the central scholar in the sociology of scientific knowledge (SSK), Bloor was the leader of the relativist faction in the ferocious, decades-long rationality and relativism debate (known in the popular press as “the science wars”). Half of his published work was on SSK—every word fiercely and widely debated—the other half on Wittgenstein—this half met with stony silence from the community of Wittgenstein scholars. I had my topic: Bloor’s reading of Wittgenstein.

It’s late in this essay to begin on Wittgenstein on analysis. I’ll quickly mention just two points, one on his critique and one his biography. Wittgenstein came from Austria to Cambridge, England and Bertrand Russell to study philosophical logic, the very core of analytical thinking. He wrote one book when very young, composed in the trenches of WWI, a book that became the “bible” of the logical positivists, the hard-core devotees of analytical thinking. Then he left philosophy. He came back to Cambridge in 1929, and spent the last twenty-two years of his life doing a very different kind of philosophy—the philosophy so revelatory to me, Bloor, and others.

Wittgenstein would be generally considered the greatest philosopher of the 20th century (or at least there are no other serious contenders). Russell called him “the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived, passionate, profound, intense, and dominating.” When the young Wittgenstein left philosophy, he thought he had solved all of philosophy’s problems. Scholars hear that and chuckle indulgently at the eccentricities of our geniuses. But I take it at face value: Wittgenstein’s early book articulated how analytical thinking works, and marked out the boundaries of what it can and cannot do. He came back to philosophy because he realized there is much more philosophy can say about the reality outside those boundaries. Russell disapproved of Wittgenstein’s later philosophy. He thought Wittgenstein had stopped doing the work, had “grown tired of serious thinking,” that he had traded in the hard edges, strict definitions, and solid conclusions of analysis for squishy, inconclusive meditations. But Wittgenstein knew that if the game is not bounded by the assumptions of your analysis—as Ed Thorp learned winning money from casinos is not—a different kind of thinking is needed.

Here’s a quick Wittgensteinian critique of analysis. In contemplating a hypothetical machine, designed to perform a certain function or move a certain way, Wittgenstein points out that machines bend, break, melt. This seems almost irritatingly off-topic when design’s relation to function is the topic. But it reminds us that we were idealizing the machine, imagining it moving just as intended. Think of the machine here as an analysis. There is an artificiality to designing and analyzing, Wittgenstein reminds us, that must be taken into account. We make machines and analyses for a purpose; they have to make their way in the real world, where things break and things change.

Wittgenstein’s philosophy is the basis of Bloor’s relativism. Many people react to relativism the way Suskind and Richardson reacted to the Bush official’s dismissal of “the reality-based community.” They think they hear some fantastical claim of freedom from the constraints of reality, and listen no further. But the truth is quite the opposite: the relativist claim is of responsibility for reality, not freedom from it; we act and reality changes, and changes again. “The way the world really works” depends on what we do beyond the static boundaries of our analyses. If we forget that, we risk forgetting to build EV charging stations, forgetting that our universities are under deadly assault, or forgetting that casinos cheat.

A striking passage in Suskind’s article inadvertently evokes the limits of analysis, and captures the dispute over Wittgenstein’s relativism. Suskind diagnoses Bush’s intellectual weakness as failing to move past his rigid Harvard Business School book learning because Bush “never ran anything of consequence in the private sector,” and so had “little chance to season theory with practice.” The real education, says Suskind, happens when graduates get jobs in the business world where they discover a more nuanced reality: “They discover, often to their surprise, that the world is dynamic, it flows and changes, often for no good reason. The key is flexibility, rather than sticking to your guns in a debate, and constant reassessment of shifting realities. In short, thoughtful second-guessing.” This post-MBA learning that Suskind describes is remarkably reminiscent of that angry Bush official’s claim about “the way the world really works.” It is also remarkably relativist.

Suskind calls this new and thoughtful flexibility “nuanced, fact-based analysis,” but that is just rhetoric paying lip service to facts and trying to cram theory and practice together under the label “analysis.” Might as well call drugged coffee and fake mustaches “nuanced, fact-based blackjack.” That line marking the boundary of inside or outside an analysis is always changeable and usually contentious. On behalf of the professional class, Suskind pushes that line out, past the boundaries that make analysis work and out onto the terrain of practice, as if nuanced and thoughtful second-guessing were just more of the same. What Bloor and some other Wittgensteinians and pragmatists do is push back the other way, arguing that even the most formal and rigorous analysis contains more “thoughtful second-guessing” than the analytical thinkers of the professional class like to admit. But that is a topic for another day.

A delightful early relativist work makes this point about the uncertainty at the heart of analysis. I’ll leave you with this piece by Lewis Carroll, whose day job, when he wasn’t writing nonsense poems and children’s classics such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, was as a mathematical logician at Oxford. In “What the Tortoise Said to Achilles,” Carroll argues (correctly) that even the simplest and most basic logical inference is inconclusive; it all depends on how we take it, our response, what we do. In the beginning was the act.