by David J. Lobina

A new year, and a new opportunity to write on some more contentious topics (and/or be cancelled), my new year’s resolution in 2024. I wrote about universality and diversity last year, as well as on the identity conditions of, well, identities, and I now start the year 2025 by reviewing a book published by Oxford University Press on inclusion in linguistics. I should warn any potential readers that this is possibly the worst book I have ever read in my career, and that it is hardly about inclusion to boot, but to understand what I mean by this one will have to read the 4000-word review I have written. I would say enjoy, but…(NB: the review is due to appear on LinguistList at some point, unless they change their minds).

*

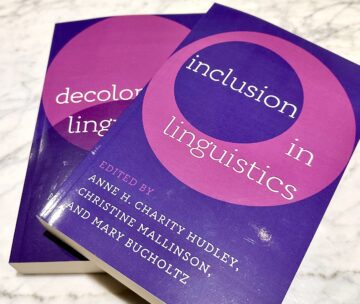

The volume Inclusion in Linguistics showcases the work of over 40 authors across 20 chapters on what is perceived to be a lack of inclusion in the field of linguistics, with North America as the main focus of attention (with some exceptions). Edited by Anne H. Charity Hudley, Christine Mallinson, and Mary Bucholtz, this collection of papers is part of a project that includes the volume Decolonizing Linguistics, also published by Oxford University Press. The overall project started in 2020 during the Black Lives Matter movement and its stated aim is to achieve equity and justice in linguistics on the basis of race, disability, gender, sexuality, class, immigration status, Indigeneity, and global geography (p. 2). As an instance of a social justice endeavour, therefore, the contributions are mostly focused on the sort of actions needed to achieve greater inclusivity in the field, and in these very terms, the editors encourage readers to use both volumes as guides for scholarly work as well as for pedagogical purposes, with further material to be had on a dedicated website.

I shall very briefly summarise each chapter first and then I will engage with parts of the content below, where I shall name the respective authors when pertinent to do so. The volume itself is divided into 4 thematic parts. Part 1 focuses on intersectional models of inclusion; Part 2 details possible institutional pathways to achieve more inclusion in linguistics; Part 3 is devoted to some of the resources available to teachers and lecturers to build more inclusive classrooms in schools and universities; and Part 4 outlines various examples of inclusive public engagement in the field. The background to the overall project is chronicled in the book’s preface whilst the Introduction describes the general approach as well as each contribution, with the Conclusion highlighting the lessons learned.

Regarding the organisation of each chapter, most contributions follow a similar template and are all equally short. The title page of each chapter except one presents the pronouns the contributors would like others to use when referring to them, whilst the actual issue at hand is usually introduced within the context of the authors’ “positionalities” – viz., short biographical sketches of their background and motivations – with most of the discussion typically centred around various recommendations and action plans to increase inclusivity.

Chapter 1 calls for a change in how linguists talk about the speech of disabled people and argues that research on autism, in particular, is based on artificially-constructed tests that have resulted in harmful conclusions. Chapter 2 stresses the lack of deaf and/or black scholars in sign language research, especially from the Global South. Chapter 3 argues that linguistics in general is hostile to people of Filipino heritage, this partly due to the exoticisation and exploitation that Filipinos suffer in North America. Chapter 4 focuses on the language around transgender people and provides a number of examples of perceived cases of transphobia. Chapter 5 describes the pernicious effects of what it calls the figure of “the lone genius” in linguistics, a variation of Great Man Theory, and among other things argues in favour of citational justice as a way to elevate the work of minoritised people (i.e., an increase in patterns of citations for the work of minoritised people). Thus Part 1.

Chapter 6 starts off Part 2 by highlighting the experiences of first-generation graduates – that is, the first person in their immediate family to graduate from university – and argues for the need of support structures for such first-generation students. Chapter 7 calls for the expansion of linguistic programmes in Historically Black Colleges, and for a more expansive definition of what qualifies as linguistics to boot. Chapter 8 describes the state of linguistic research in India, claims that it is too theory-focused, and suggests that the interested scholars need to consider social aspects too. Chapter 9 is devoted to Natural Language Processing research and the well-known dataset biases that plague the development of language models, offering some mitigating measures as a possible solution.

Chapter 10 kickstarts Part 3 with a call for linguistics to be part of a social justice curriculum pivoting on antiracism. Chapter 11 reports efforts to incorporate the teaching of Cape Verdean Creole in specific bilingual settings in North America. Chapter 12 calls for linguistics to act as a force for social change in community colleges, especially in order to attract more people of colour to the field. Chapter 13 outlines one way to attract more students of colour to the field: by using data and examples from students’ own linguistic interactions. Chapter 14 explains the possible role of what the authors call land-based knowledge in linguistics. Chapter 15 has some advice on how to conduct so-called pronoun rounds: a classroom exercise where students identify which third-person pronouns they would like others to use when referring to them. Chapter 16 exemplifies one way to make university lectures more engaging by employing an “active learning pedagogy”. Chapter 17 describes a repository of open-access pedagogical tools to make lectures more inclusive, including a database of diverse names for the creation of more expansive linguistic examples.

Lastly, Chapter 18 offers some pointers on how to make linguistics more approachable through public engagement. Chapter 19 argues for the need to offer “critical language awareness” workshops to primary and secondary students, as in a recent initiative in Boston. Chapter 20 discusses linguistic outreach programmes in relation to identity and cultural issues. Thus Part 4, and the bulk of the volume.

What to make of it?

Well, it is hard to believe this book exists at all; or rather, it is hard to believe that Oxford University Press has published this volume under its Oxford Academy section. Inclusion in Linguistics is mostly a product of political advocacy, not of scholarship, and whilst this is not necessarily a bad thing in itself, the problem here is that both the politics and the advocacy on display are incredibly tendentious. The book is populated by myriad claims and denunciations, and even though most of these are rather contentious in nature, they all go largely unargued for (in addition, some material is close to mockery and even slander, and one has to wonder what OUP were thinking; more about this below).

The book is also rather parochial in outlook; most of the arguments and claims can only be understood within the context of certain social and political undercurrents in North America, some of which the contributors happen to exemplify quite neatly, and there is furthermore a fair amount of preaching to the already converted, this more clearly in evidence when it comes to the significant amount of jargon the reader encounters, which is rarely defined let alone explained – it is instead simply assumed to be common currency, and moreover correct. As a case in point, much of the material in this volume will be largely incomprehensible to most readers in Italy, Spain, and, to a lesser extent, the United Kingdom, the three countries I know well, and partly because of the language (also, the book alludes to social conditions that don’t really translate to those three countries).

The general ethos, to now focus on this aspect of the book, is not a little partisan too: the preface denounces the apparent fact that scholarship is dominated by white cis male discourse, with the contributions meant to offer relevant alternatives, as per the expectation that diversity (of race, gender, ableness, etc.) produces different kinds of scholarship, whilst the Introduction identifies, as already stated, the Black Lives Matter movement as the relevant background to the overall project, and in particular the murders, as the editors stress, of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Both positions merit some commentary. The second point rests on a mistaken equivalence, as Breonna Taylor was accidentally killed in crossfire and no-one has ever been charged with murder or even manslaughter, unsurprisingly so. This is not meant as a petty and pointless correction, but as a way to highlight the comprehensive partiality of the overall project.

Regarding the mention of white cis male discourse, more importantly, I must admit that this claim did not elicit a belief that some perspective is sorely and unjustifiable lacking in linguistics, but instead recalled, unfortunately, past talk of “Jewish Physics” – and, in the event, no characterisation of what a white cis male discourse actually is was forthcoming in either the preface or elsewhere in the volume (incidentally, Jewishness makes one single, brief appearance in the volume, if the search function of the Open Access pdf file is to be trusted; the Press has not bothered to include an index in this volume).

Moving on to the scholarship, the editors start off the volume by explicitly rejecting some of what many would regard as basic tenets of Wissenschaft – a German term that is more expansive than the English word “science”, thus involving the human sciences, and meant to refer to scientific fields that ‘involve rigorous and teachable methods for investigating and acquiring knowledge about their subject matters’ (Leiter, 2024). In the Introduction to the volume, then, the editors denounce and moreover reject the notion that ‘research discovery and scholarly knowledge must be personally distant or seemingly objective for the author to have authority and expertise’, a position they claim constitutes a case of colonialism and white supremacy (pp. 15-6), though no explanation or justification is given for the sweeping statement. Similar sentiments are expressed in many of the contributions, again with little to no elaboration, and usually presented as simple statements of fact. Readers who might view the editors’ position on science and the systematic pursue of knowledge as not a little preposterous will be excused for quickly skimming through the book, or giving it a pass altogether. More importantly, perhaps, such views can have the unfortunate effect of antagonising those of us who might otherwise be sympathetic to some issues from the volume, and who would have welcomed more detail – and some argumentation.

Consider further examples from the actual contributors. Lynn Hou and Kristian Ali, in chapter 2, draw a sharp distinction between the epistemologies of the Northern and Southern hemispheres, as per a model of Boaventura de Sousa Santos, according to which academia from the Global North is not to deferred to and academia from the South is to be privileged so that it can be liberated from the shackles of the Global North (pp. 38-39). Julien De Jesus, in chapter 3, casually mentions that both the Philippines and the United States are false countries and false nations, argues that the term Filipino needs to be replaced by Filipinx by analogy to Latinx vis-à-vis Latino, and takes it for granted that there is structural racism in linguistics (p. 65; the terms Filipinx and Latinx are not common in the Philippines and Latin America; they are the product of North American politics and are not, in fact, universally accepted there, either). Deandre Miles-Hercules (styled as deandre miles-hercules in the book), in chapter 4, assumes that a commitment to scholarship must entail a principled investment in dismantling oppression. Rikker Dockum and Caitlin M. Green, in chapter 5, warn against the pernicious effects of the figure of the lone genius and Great Man Theory, both of which are ‘mired in Western chauvinism, Eurocentrism, scientific racism, and prejudiced language ideologies masquerading as objective facts’ (p. 100), and as such there is a need for reparations and restorative justice (p. 105). Candice Y. Thornton, in chapter 7, claims that linguistic methodology as currently practiced results in data that often perpetuate colonial hegemony. Emily M. Bender and Alvin Grissom II, in chapter 9, claim that large data sets as employed in contemporary language models preserve systems of oppression, including racism and misogyny, and thus are skewed towards hegemonic views (p. 206), a reflection of the coloniser’s mentality in the field of Natural Language Processing (p. 212). Rhonda Chung and John Wayne N. dela Cruz, in chapter 14, describe modern Canada as a settler-colonial state and refer to something they call “raciolinguistics ideologies”, which are used to justify and maintain monolingual, Eurocentric, and white supremacy structures. Lal Zimman and Cedar Brown, in chapter 15, have it that academic freedom is a supposedly apolitical concept that is in fact often mobilised to protect and sustain the influence of racist and transphobic oppressive ideas (p. 314). E così via…

I really need to stress that the vast majority of these claims are not defended or substantiated in any way in the book; they are mostly presented, as already mentioned, as statements of fact – too obvious to require any elaboration, or indeed any references as support. Surprisingly for what is meant to be an academic book, moreover, some material is rather unbecoming. Certain admissions, in particular, come across as rather unedifying, and reflective of personal prejudices and grievances. Two examples will suffice here. Jon Henner, in chapter 1, recounts a chat with a group of women in pre-flood New Orleans, at a time where Henner admits he ‘had more patience for engaging in oral conversation with hearing people’ (p. 30), whilst De Jesus, from chapter 3, devotes much of their biographical sketch to list many of the perceived slights received in the past (macro/micro aggressions, in the parlance of the volume); in neither case, however, do such admissions add anything to either the arguments or the content of these chapters.

This is generally the case whenever authors’ “positionalities” are shared in the volume; contrary to the overarching assumption in the volume that one’s past history and personal motivations can explain and affect scholarship, I perceived no direct relationship between the biographies of each scholar and their academic views – what I did perceive was SOME connection between these biographies and the political beliefs and advocacy of the authors (including, as mentioned, prejudices and grievances), though even here I would not exaggerate the link, superficial as it is.

Worse still is the behaviour of Miles-Hercules, from chapter 4. I have already mentioned the claim in this chapter that a commitment to scholarship must entail a principled investment in dismantling oppression; Miles-Hercules also believes that those academics who are not keen on discussions or initiatives about inequality in higher education would do well to ‘steer far clear of academic occupations’, perhaps to dedicate themselves to veterinary acupuncture (p. 85; I fear the advice regarding this alternative employment is not offered in good faith, though). Miles-Hercules also claims, with no evidence, that the work of gender critical feminists incites transphobia, and in the event refers to these scholars as TERFs and FARTs (pp. 88-89), terms that by now are often used as slurs, as seems to be the case here. One Ráhel Katalin Turai comes in for particularly nasty treatment in this chapter for the temerity of having sent a critical email to Miles-Hercules on the occasion of a past event, and is effectively defamed as a transphobe in the chapter. We are thankfully spared the tiresome prospect of going through the actual contents of the email and are offered paraphrases instead, interspersed with Miles-Hercules’s rebuttals, but only because Miles-Hercules believes that emails are protected by intellectual property law in the US and thus cannot be publicly disclosed (this does not seem to be correct, but this is by-the-by now).

It is certainly disappointing for an academic publisher such as Oxford University Press to allow publication of such gratuitous attacks, which certainly have no place in scholarly publications, and I am surprised the legal team at the publisher’s UK headquarters did not identify any potential legal issues (the copy I received was published in the US rather in the UK, where libel laws are stricter, but I assume the book has also been published in the UK).

So far, so political (advocacy), but there really is very little scholarship to discuss in the volume. I will mention one issue below that is more or less academic in nature in order to close this review (such as it is), along with some comments about lost opportunities.

I will not discuss, however, any of the recommendations on offer regarding how to increase inclusion in linguistics (not even the “call shit out” advice form chapter 3, though I have taken that to heart), most of which have little to do with academia and academics per se and more to do with society at large (many recommendations, moreover, strike me as potentially negative and against well-established, and well-justified, academic norms). This is unsurprising, given that inclusion and diversity are societal issues that require structural changes and government policy, and for which, I would argue, the concept of class (and equality rather than equity) would be the most important factor, and not the “identities” to do with race, gender, etc., so obsessively emphasised in the book (as an aside, in the UK some of these identities are codified as “protected characteristics” in the 2010 Equality Act as a guard against discrimination, a nomenclature that strikes me as much more apt; after all, there is much more to a person than their personal characteristics of race, sexuality, etc.).

I should add that I find the kind of talk on inclusion and diversity in the book surprisingly divisive, and furthermore surprising coming from linguistics; divisive because the language around diversity is often couched as if people of different characteristics lived in different realities as somewhat “closed groups” – or trapped in cultural enclosures, as Jürgen Habermas has put it (see here); and surprising coming from the field given that linguists have often emphasised the theoretical validity of any of the world’s languages to the enterprise of studying universal properties of the language capacity (I have discussed universality, diversity, and language in here and here; the former argues that diversity needs to be understood within the concept of universality; the latter revisits the work of the anarchist thinker Rudolf Rocker and in so doing includes discussion of national languages and standards, topics touched upon in the volume too).

Regarding the limited scholarship present in this volume, then, the book contains various criticisms of linguistics as a field that are worth considering. Take Thornton’s contribution again, from chapter 7. In a passage in which Thornton discusses an article of Frederick Newmeyer’s on the history of linguistics (cited therein), we are offered this stream-of-consciousness reaction (I let others judge the tone):

so he just gon’ act like Greek scholars ain’ learn from KmT?! Like people of the African diaspora (pre and postcolonial contact) weren’t exemplifying linguistics, philosophy, and rhetoric through diverse oral traditions?! Like languages of the African diaspora ain’ been explicitly articulatin’ and signifyin’ all the cosmologies, epistemologies, and ontologies?! (p. 155)

where, by KmT, I gather the author means the more common “kemet”, the term Ancient Egyptians seem to have used to refer to the black soil around the Nile Delta (and thus, perhaps, to refer to the Nile Valley; in either case, nevertheless, these are reconstructions and thus modern interpretations), though here it seems to be related to those strands of Afrocentrism that use the term to refer to black Africa, as Thornton appears to intend.

The criticism levied at Newmeyer misses the target, though, for Newmeyer is talking about the origins of what may be termed theoretical (or structural) linguistics, and that is not what Thornton has in mind at all, as is clear from the quoted passage. Theoretical linguistics is certainly not all there is to linguistics, moreover; I myself studied at a department once regarded very much as one mostly focused on theoretical linguistics (and on generative grammar to boot), but there were also many courses in sociolinguistics, historical linguistics, linguistic anthropology, and much else (courses at the interface between linguistics and other fields, such as literature, were also available). Linguistics writ large is, well, a large field of study, and different aspects of language are studied at different levels and with different methods. Interdisciplinary, after all, is a reality of modern scholarship as much as the well-cemented principle that subject matters need to be properly delimited for scientific study (both points are of course rejected in various places in the volume; chapter 5 talks of disciplinary divisions as false dichotomies, for instance). And, in any case, I note that Oxford University Press classifies this volume under its Sociolinguistics category, along with the related areas of Linguistic Anthropology and Social Theory, so what is the issue exactly?

Thornton’s sentiment is echoed elsewhere in the book. In the context of exclusion rather than inclusion, the editors mention that ‘[l]inguists who focus on the languaging of the mouth and its internal and external movements do not consider themselves obligated to include the languaging of the hands and the body’ (p. 10). Again – and taking the term “languaging” to mean “use of language” for now (the term is used over 40 times in the book, but receives no definition) – this is not a situation I have encountered myself (and the editors offer no examples); if anything, the addition of scholarship on sign language as another window into the study of the capacity for language has been very prominent in the field, along with many other sources of data (experimental, historical, etc.).

All in all, it seems to me that the situation in this volume is as follows: many of the authors do not seem to believe that their subject matter or field of study is scientific or involves systematic knowledge as these concepts are customarily understood (as Wissenschaft), whilst some of the authors seem to confuse (or indeed conflate) scientific study with political advocacy. If the former is the case, then one needs to ignore the talk about positionality and identities and instead just judge whether the knowledge on offer adds to Wissenschaft or not, regardless of where it comes from. If the latter is the case, though, one needs to recognise that political advocacy is not Wissenschaft and advocacy need not always be the concern of scholarship.

There are myriad examples of such conflations in the volume. Consider Miles-Hercules again, who actually starts chapter 4 by bringing up a controversial post from the blog Language Log from 2017 involving Geoffrey Pullum (Miles-Hercules also references, though obliquely, another post involving Pullum which proved controversial too, this one discussing the use and mention of the N-word, but this plays no role in the chapter and I suspect it was added for effect). The post Miles-Hercules focuses on has Pullum make a linguistic point about the use of singular “they”, which at the time unfortunately degenerated into a long discussion in the comments section on how the modern usage of “they”, in the context of a person who identifies as bisexual and wishes others to use “they” when referred to, ought to override a person’s grammatical knowledge regarding which linguistic contexts the word “they” can and cannot appear in, including which antecedents “they” can and cannot take. Any argument to the contrary (or any nuanced disagreement) gained Pullum and others little more than abuse at the time – accusations of misgendering and transphobia abounded – and this remains so now, with Miles-Hercules defaming Pullum in the very same terms here. I should add that, for whatever reason, Pullum stopped writing on Language Log soon after these controversies, and this has been to everyone’s loss, in my opinion.

In any case, this is a reflection of the failure to distinguish between political advocacy (or, in reality, the requests of particular individuals as to how they would like to be referred to by others) and actual theoretical points regarding the internalised and systematic knowledge of language of a person – and, thus, constitutes an unfortunate lapse into ideology.

I earlier alluded to lost opportunities. There was plenty of useful information in the book as well as a number of interesting surveys and interviews (though the samples were far too small for the conclusions that are drawn from them), but most issues of relevance were treated far too briefly and far too superficially. Some topics deserved more thorough and sustained discussion – the history and current status of Historically Black Colleges is a case in point – and a wide readership would have been found for a more judicious book (and perhaps even an international readership if the approach had not been so insular). What we have instead is a book displaying incredibly tendentious and parochial politics, poor scholarship, and an angry and divisive tone throughout, resulting in an exhausting to read list of claims, denunciations, grievances, and disqualifications. Most contributors had, quite simply, an axe to grind here, but what they described in their chapters was often more a case of how they would like the world to be instead of what the world really is like.

The reader could have been spared some of the mockery and slander too if the editors had not been so inflexible. In the preface, we are told that the project decided against a regular reviewing process for each contribution because, of course, this is susceptible to colonisation (p. xviii), opting instead for group workshops and revisions. It is not unreasonable to believe that a regular reviewing process could at least have avoided the worst excesses typical of political group thinking. No doubt the editors view such a reviewing process as an example of the gatekeeping ideologies they denounce in various places in the book, ideologies that ‘rely upon assimilatory replication models of academia that are grounded in and designed to maintain white-supremacist, colonial, normatively embodied, abled, and cis male-hegemonic views…[continues ad nauseum]’ (p. 444).

The volume could at least have been printed on recycled paper, but alas, this was not to be.

Author’s positionality: David J. Lobina specialises in cognitive science tout court and that is all you need to know.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.