by Brooks Riley

Richard Wagner’s mammoth Ring of the Nibelung cycle begins with a single note—not a chord, or series of notes, or leitmotif—but an extended E flat so deep it could be mistaken for noise, or the rumblings of Earth giving birth to tragedy. Hours later, this Ur sound, produced by eight contrabassi over four measures, will hardly be remembered after so many other sounds have competed for the listener’s attention. But the effect lingers on, deep in the psyche.

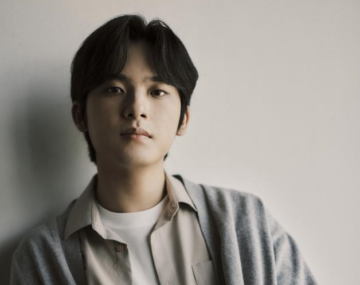

Someone else who understands the power of a single note is pianist Yunchan Lim, winner of the 2022 Van Cliburn competition at age 18, who electrified the classical music community with his performances of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 3 and Liszt’s Transcendental Études and has since sold out concerts around the world. His reputation for virtuoso barrages of perfect notes at dizzying speeds belies a deep engagement in the sound he can extract from the piano with a single note—a process he demonstrated in an interview for Korean television last May.

Someone else who understands the power of a single note is pianist Yunchan Lim, winner of the 2022 Van Cliburn competition at age 18, who electrified the classical music community with his performances of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 3 and Liszt’s Transcendental Études and has since sold out concerts around the world. His reputation for virtuoso barrages of perfect notes at dizzying speeds belies a deep engagement in the sound he can extract from the piano with a single note—a process he demonstrated in an interview for Korean television last May.

‘In my mind, there’s always a feeling of what I think is the truly perfect sound. That sound exists. When the sound in my mind perfectly matches the sound in reality, at that moment, I feel my heart moving.’

As a percussive instrument, the piano is not very malleable. The tone of a single note occurs far from the finger that hits a key to activate a hammer to hit a string. Variety of tone depends on the force with which the finger has hit the key, or where on the key the finger has hit, as well as the use of pedals to amplify and elongate the sound or to mute it. The piano has no vibrato, for which one can be grateful, considering how many other instruments depend on it.

‘. . .when I press the G-sharp key, if it strikes my heart, then I move on to the next one. . .If my heart doesn’t feel it when moving to the A-sharp key, I keep doing it. . . . if the A-sharp key strikes my heart, then I practice connecting the first and second notes, and if that connection strikes my heart, then I move on to the third note.’

This may be one reason why his practice sessions are so long, often late into the night, or why he once spent hours on two measures of a Schubert Sonata. For Lim, technical brilliance is a given. What’s important to him are tone, color, rubato, feeling, poetry, poignancy, interpretation—even if he is wary of sentimentality or too much emotion.

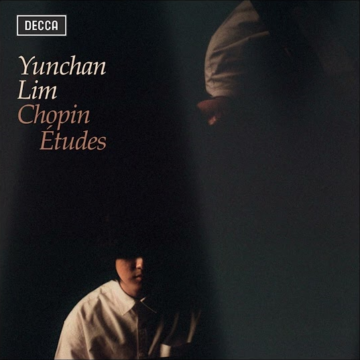

Speaking of his Decca recording of the complete Chopin Études: “A man-made garden may fool us into thinking it is beautiful. I tried hard not to fall into that illusion. Rather than aiming to hit every note perfectly, I focused on incorporating a more musical interpretation. I also aimed to create music that was less beat-driven and more free-flowing.”

What sets Lim apart from other young winners of important competitions?

With Lim, there is a quantum leap that no one quite fathoms or even dares to believe. As conductor Marin Alsop described him to the New York Times, ‘He’s a musician way beyond his years. . .Technically, he’s phenomenal, and the colors and dynamics are phenomenal. He’s incredibly musical and seems like a very old soul. It’s really quite something.’

This ‘very old soul’’ resides in a shy, self-effacing young man of 20 who lives and breathes music to such an extent that his goal in life is to live on a mountain and play the piano all day long.

Lim started late, at age 7, but his trajectory to the top has been short and steep. Long before the Van Cliburn competition, he was recognized as a prodigy in his home country of South Korea. He still studies with pianist Minsoo Sohn.

Sometimes Lim carries his self-effacement too far: ‘I’m just a person who makes music, and I’m not much of a person at all.’ Or ‘I’m not the kind of person who deserves this kind of applause.’ His discomfort at standing ovations is evident even if he tries to hide it. Watching him take bows, one gets the feeling he can’t wait to leave the stage.

What may sound like false modesty is most likely respect for the music that has propelled him to stardom almost overnight. There’s no room for flamboyance or an outsized ego in Lim’s universe, where music is the star, not the performer. His modesty runs deep.

For the Decca recording of the Chopin Études, he chose the picture to be used on the cover—his way of nearly disappearing behind the music.

When he’s not practicing, he’s listening to the greats who have preceded him (Vladimir Sofronitsky, Alfred Cortot, Josef Lhévinne, Ignaz Friedman, Artur Schnabel, Ervin Nyiregyházi and Evgeny Kissin), or researching a composer’s life (Chopin ‘purposely put himself into lonely situations for his art’s sake. He continuously refined his composition until he created the perfect crystal of his music.’ Lim could be describing himself), or delving into source material (For Liszt’s Dante Sonata, he read and memorized parts of the Divine Comedy.)

I saw Lim for the first time on YouTube live during the Van Cliburn competition. Hearing him play feels like eavesdropping on an interior dialogue. He may be performing in front of an audience, but he could be on a mountain top. We just happen to be there with him. It’s a connection that transcends the typical performer/audience dynamic.

A vivid narrative clearly runs though his mind as he plays, surfacing in the rare odd smile or slight grimace. Asked what he was thinking about when playing the Chopin Étude Opus 25, Number 1, the ‘Aeolian Harp’, he said ‘I don’t know why, but it evokes imagery of a goose opening the door to the world, gazing at the crescent moon on its first night, reminiscing about its dreams.’

Jeremy Nicholas of Gramophone has written: ‘To follow Lim on YouTube is to go down a rabbit hole: once you start viewing, it is very hard to stop.’ There are Lim performances going back to his recent childhood. But the latest ones, from Verbier or Wigmore Hall, reveal his special relationship to the single note. It can be seen in the way he plays, how a finger creates the sound of a bell, or a thunderous clang in the lower registers. His hands often hover over the keyboard or seem to be sculpting the air before dropping down to caress the keys, as seen in this performance of Tchaikovsky’s ‘June’ from The Seasons.

There are few ‘wait and see’ critical responses to his concerts. Most critics are running out of superlatives to describe what Lim does—how he plays so effortlessly, like a seasoned pro, with such musical maturity—or how he fashions an emotional interpretation as if he had already lived a long life and experienced the joys and pain of love. His recordings have been called ‘triumphs’.

“The real things in this world are invisible to the eyes. Because music is invisible.’

Yunchan Lim has created that mountain in his mind—a place of joy and sound where he studies, builds and practices his musical repertoire. He may leave it to meet with his musician friends to gain inspiration from them. If there’s time left over he reads Rilke, his favorite poet, or Heine, recommended by his teacher.

In the two years since the Cliburn, he’s grown taller and somewhat less diffident. Even in Korean he speaks haltingly, as if his words were trying to cross a river swollen with musical notes to get to us.

According to the Korean custom of acknowledging a next life, Lim has already divided his musical challenges between this life and the next one. There are simply too many works he wants to master for a single lifetime. He aims to be a pianist like Trifonov who can play everything, from baroque to modern music.

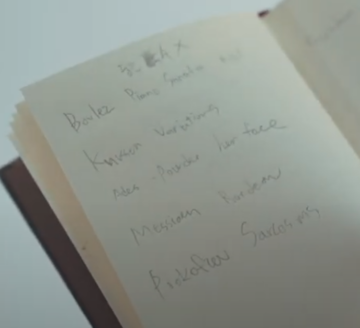

In a 2020 interview for the Korean Symphony, Lim showed a random page from his notebook with an imaginary concert program: Pierre Boulez Piano Sonata, Oliver Knussen Variations Opus 24, Thomas Adès Powder her Face, Olivier Messiaen Rondeau, and Prokofiev Sarcasms. What 16-year-old makes plans like this?

This life or the next?

Playlist

The winning Rachmaninoff Concerto No. 3 performance at the Van Cliburn competition 2022. 16 million people have watched this video.

Ben Laude at Tonebase Piano: a fascinating and entertaining analysis of Lim’s performance of ‘Rach 3’, including remarks by two members of the jury.

Lim’s historic semi-final performance of Franz Liszt’s Transcendental Études , a technical and artistic tour de force

Final movement of Beethoven Concerto No.5 (the Emperor) with Gwangju Symphony Orchestra 2022. Lim has a special relationship with this orchestra. He is unusually animated in this lively excerpt.

NPR Tiny desk concert In this video, Lim manages to ‘transform’ an old upright piano into a concert grand. Franz Liszt’s Sonetto del Petrarca No. 104 , the first of three pieces, is amazing.

Classical Musicians React This YouTube Channel features young classical musicians, some of them students. Their take on Lim’s performance at NPR’s Tiny Desk Concert is both entertaining and educational.

Mendelssohn’s Song Without Words, Opus 85 No. 4, from the Verbier Festival 2024

Tchaikovsky’s May from The Seasons. In this television performance, he offers glimpses into his way of approaching a work. Hints of synesthesia can be noted in his use of colors to describe a musical moment.

Two short interviews with Lim for the Korean Symphony 2022 and Korean Symphony 2020 are both revelatory.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.