by Akim Reinhardt

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

2016 and 2020 were almost certainly among those elections, though academic historians have not yet written much about them (or even Obama’s 2008 election) because we typically wait a couple of decades before sensing that an event has passed from current or recent events into our distant domain. And anyway, it’s quite possible, even likely, that many future historians end up examining the three Trump elections of 2016, 2020, and 2024 as a bundled set.

But that still leaves about 55 elections historians have focused on and learned lessons from. So here on Election Day 2024, I offer brief summaries of select, momentous presidential elections and explain how they connect to this current Trumpist era and today’s electoral contest.

1800– George Washington won uncontested elections in 1788 and 1792. By then, he was a wildly popular war hero and founding father who could have held onto the office. Some Americans even called for him to become a king. But Washington valued the new republican experiment, and also wanted to go home, so he stepped down. In doing so, he set an important precedent that lasted nearly 150 years. No future president, no matter how popular, attempted to serve more than two terms until Franklin Roosevelt disregarded tradition and won four consecutive presidential elections (1932–44).

In 1796, John Adams defeated Thomas Jefferson in the first truly contested presidential election. Four years later, Jefferson bested Adams in the rematch. For the first time, a sitting president lost an election and had to step down despite his best efforts to hold onto the office. And despite two rather nasty campaigns between Adams and Jefferson (No, it’s not a recent phenomenon.), Adams stepped aside, unhesitatingly and gracefully, and retired to Massachusetts. Adams’ precedent was arguably even more important than Washington’s. Establishing peaceful transitions of power after contested elections is a vital component of a healthy, functioning democracy. Many new democracies founder the first time a sitting leader faces an electoral loss and doesn’t want to give up power. But the United States pulled it off, first with Washington’s precedent, and then with Adams’. And every single presidential transition of power since then was peaceful, until 2020.

1826– Lawyer, general, land speculator, ethnic cleanser, plantation slave owner, winner of several duels, and former teenage prisoner of war during the Revolution, Andrew Jackson first ran for president in 1824. In a five-way race with low voter turnout, he garnered a plurality of both popular and electoral votes, but a majority of neither. As the Constitution stipulates, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives where each state delegation got 1 vote. After some horse trading, the House elected former president John Adams’ son, John Quincy Adams. Jackson was irate. His supporters labeled it a “corrupt bargain.” In truth, there was nothing corrupt about. It was literally politics. Adams was better at politicking, while Jackson had many enemies, which came back to haunt him. So he ran again in 1828, and that time he beat Adams. But what’s relevant is how he did it.

The second time around, Jackson joined forces with New York Gov. Martin Van Buren to create the first modern political party, now known as the Democrats. He also ran as the first populist. Every president before him (Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, J.Q. Adams) had been a wealthy, educated elite, and proud of it. Jackson was too, of course, but he played up his Old Hickory personality, positioning himself as the common man’s champion. Why? Because middle class and even poor white men finally gained voting rights during this era. Stupendously wealthy, Jackson painted himself as the rough and tumble everyman. It worked. As it has for notorious rich kid Donald Trump. No wonder Trump kept Jackson’s portrait in the Oval Office.

1860– Abraham Lincoln topped the ticket of a fairly new political party. In 1854, the Republican Party formed when refugees of the recently defunct, pro-business Whig Party: co-opted the single-issue anti-immigration American “Know Nothing” Party; courted that era’s religious social reformers; and embraced the North’s then-predominant anti-slavery stance, called Free Soil. Slavery thrived in the South, but barely still existed in the North, and Free Soilers were fine with that status quo. They are not to be confused with abolitionists, who were still a tiny minority. But Free Soilers did not want slavery (or Black people, for that matter) in the new Western territories and states. Southern slave owners did.

Lincoln won the 1860 election with a clear majority of electoral votes. However, he garnered less than 40% of the popular vote, and did not win a single Southern state; Republicans had virtually no presence in the region. Many Southern slave owners were unwilling to accept the result, not on grounds of corruption, but because they believed Lincoln represented only Northern interests and was hostile to theirs. In reality, Lincoln openly promised Southerners he would do nothing to end slavery in the South. But that was not enough. Seven Southern states seceded before Lincoln was even inaugurated. In more modern times, growing numbers of Republicans refused to accept the legitimacy of Barack Obama’s elections, and I need not explain the imperfect but very real comparisons between the Southern attack on Ft. Sumter and the January 6 attack on the Capitol.

1876– Andrew Jackson had stomped and whined about the 1824 result, but he did not formally contest it. The first formally contested election came during the nation’s centennial year. On election night in 1876, Rutherford B. Hayes (R-OH) and Samuel J. Tilden (NY-D) both went to bed thinking Tilden had won. If so, he would become the first Democrat in twenty years to win a presidential election. However, Hayes’ campaign advisors stayed up late and calculated that their man would win if three states eventually fell their way: South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana. All three seemed to be going for Tilden, but only because massive white terrorism campaigns had kept Black voters from the polls.

Some Southern states eventually sent competing Electoral College electors to Congress. Democrats filibustered Congressional acceptance of the votes, and it took until early 1877 to sort out the Compromise of 1876. Eventually, Republicans got the White House. Democrats got: thousands of patronage jobs by having Hayes appoint a Democrat as Postmaster General position; promises of a trans-continental railroad across the South; and the full withdrawal the last U.S. Army troops from the Reconstruction South, sealing the dwindling fates of African Americans there and condemning them to a century of violence, exploitation, segregation, and disenfranchisement. There was not another contested U.S. presidential election until the 21st century.

1896– By the Gilded Age (ca. 1870s–1890s) lots of Americans had lots of gripes about the boom/bust cycle of emerging capitalism and rampant political corruption. Increasing numbers of them alo felt neither party represented their interests. This would eventually culminate in what Historians refer to as the Progressive Era (ca. 1890s–1920), a period of widespread reform with wide ranging agendas. At the forefront were farmers, who still composed nearly half of the labor force. They were unhappy with banks, railroads, corrupt politicians in the pockets of banks and railroads, and a conservative monetary policy that pegged the dollar to gold. They first organized after the Civil War in rural social/professional clubs called granges. These eventually formed into to regional alliances in Midwest and South. And in 1892, those two alliances joined forces to form the People’s Party, a major third-party challenge to the Democrats and Republicans. Their members were called Populists.

People’s Party nominee James B. Weaver lost the 1892 presidential election, but he put the major parties on notice by winning five western states that added up to nearly 10% of the electoral vote. Populists were poised to make a serious run in 1896, but Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan undercut them by co-opting many of their issues. Confounded, the Populists also nominated Bryan in absentia, though he refused their overtures. Bryan eventually lost to Republican William McKinley, but by co-opting much of the People’s Party agenda, the Democrats (and the Republicans) were fundamentally changed. Soon they would espouse progressive ideals, in not entirely dissimilar ways to how the early 2010s GOP incorporated the outsider Tea Party movement and was then transformed by it.

1928– Every now and then a presidential election is bitterly divisive in ways that mirror larger divisions plaguing the nation. 1860, which was effectively a referendum on slavery, is the preeminent example. But perhaps no election crystalized so many social divisions as the 1928 contest between Herbert Hoover and Al Smith. The issues dividing Americans in the 1920s included: immigration, race, religion, alcohol, sabbatarianism, and rural/urban tensions. Republicans Hoover, an Iowa WASP who supported prohibition. Democrat Smith was a NYC native, the son of Irish, Catholic immigrants, opponent of prohibition, and lifelong member of the notoriously corrupt Tammany Hall political machine. Hoover’s supporters smeared Smith as the candidate of Rome, Rum, and Rebellion, meaning Catholicism, legal alcohol, and corrupt Tammany Hall. Hoover steam rolled him, winning 40/48 states and nearly 60% of the popular vote. Hoover’s pulverizing victory was a Roaring ’20s capstone for the conservative agenda of prohibition, immigration restriction, and laissez-faire economics. No election afterwards so distilled nation’s brewing divisions. Until 2016.

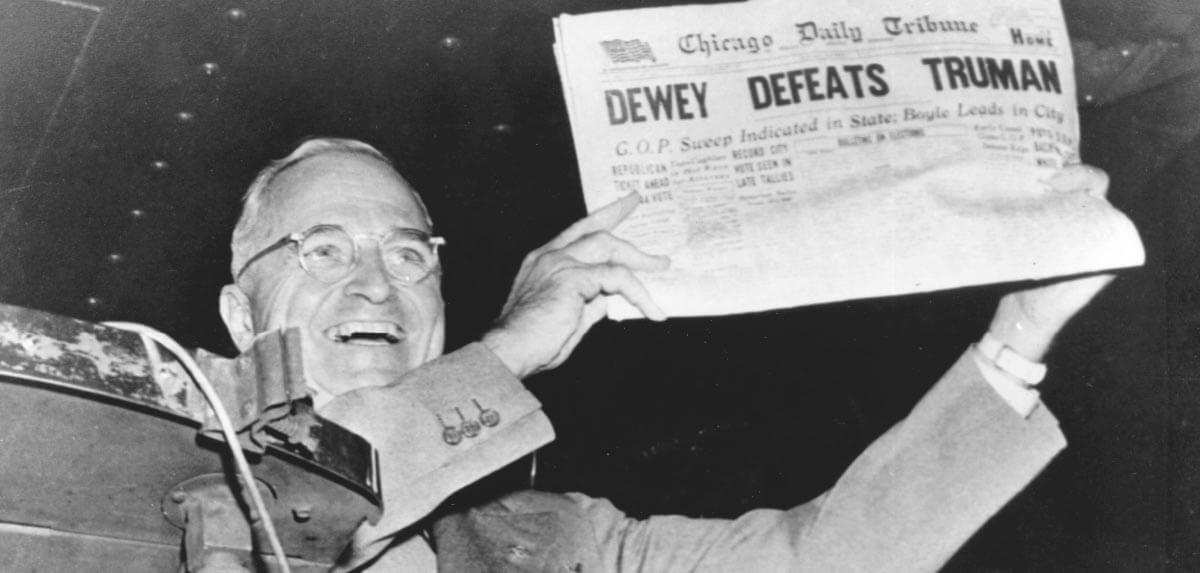

1948– Incumbent Harry S. Truman was already up against Republican Thomas Dewey when he faced a rebellion within his own party. Truman’s pro-civil rights stance led South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond to exit the Democratic Party in the name of racial segregation and run as a third candidate on the Dixiecrat ticket. Everyone assumed Dewey would win because A) Thurmond’s candidacy would split the Dmocrativ vote, and; B) as was the case in 2016, the polling stunk. In 2016, many Americans were embarrassed to admit they would vote for a foul-mouthed, racist, sexist, rapist, thereby skewing poll results. In 1948, pollsters relied on phone calls, but many Americans, particularly among the working class, did not yet own phones, thereby skewing poll results. On election night in 1948, some newspapers trusted the polls and called the election for Dewey in their upcoming morning editions, only to be shamed the next day. In 2016, many assumed Hilary Clinton could not lose only to awake to shocking news.

1980– Ronald Reagan’s landslide victory over incumbent Jimmy Carter was due to many factors. Among them was how he campaigned on Cold War patriotism, bringing together many Americans who craved national unity after the divisions Vietnam and Watergate. However, the neo-Conservative movement Reagan helped bring to power began encouraging Republicans to see Democrats not as the Loyal Opposition, but as enemies to be defeated at any cost. The Washington Consensus, a post-WWII era in which the two major parties were more similar on policies than they ever were before or since, began to erode. What gradually replaced it was forty-four years (and counting) of widening political divisions in which Republicans increasingly saw Democrats’ policies, and now even electoral victories, as illegitimate.

2000– It was nearly a quarter-century ago, but no doubt many 3QD readers still remember the controversy over “hanging chads” in Florida and the partisan, 5-4 Supreme Court decision in Bush v. Gore that effectively ended the Florida recount and any chance of Al Gore winning the presidency. Historians don’t deal in what-ifs such as What if Gore had been president instead of Georg W. Bush on September 11, 2001? Would he have maintained the national unity spurred by the tragedy of 9-11, instead of squandering it like Bush did by concocting lies to justify invading Iraq? Who knows. It’s hard enough to study what actually happened, much less what might’ve. And what did happen was that for the first time in nearly 150 years, one candidate launched a serious, legal dispute over presidential election results. Aside from handing the election to Bush, it left tens of millions of Americans feeling the results were less than legitimate. Twenty years after the Republicans had begun to see Democrats as illegitimate, Gore v. Bush jump started Democrats’ views of Republican illegitimacy. Even worse, it laid the groundwork for the modern public to doubt the veracity of election results, thereby sending the U.S. democracy to the brink of dysfunction and revolution.

2024– If studying the past teaches you anything, it’s that predicting the future is folly. It is impossible to know what’s next. But if you study the past effectively, nothing that comes will ever surprise you. You might be unhappy, depressed, concerned, or angry, but it will all seem at least vaguely familiar. Indeed, there is nothing new under the sun. We’ve seen this before, at one time or another, in one way or another. Sometimes it ends well. Sometimes it does not.

Look hard. Squint. If you recognize that Donald Trump poses a very real threat to democracy, not only in the United States but around the world should he be elected, and you haven’t already voted, then go vote. If you do not recognize that Donald Trump poses a very real threat to democracy, then you probably also don’t recognize that you are a classic example of why the Founding Fathers didn’t want most people (and almost certainly you) to vote.

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.