by Bill Murray

Countries can be sensitive as teenage girls about their names. The change from Turkey to Türkiye aligned Türkiye’s name in Turkish with its internationally known name, but mainly, disassociated itself from the bird with the goofy reputation.

Some countries’ names become less ethnic (Zaire to Democratic Republic of the Congo) and others more (Swaziland to Eswatini). Some countries change their names for politics (Macedonia to North Macedonia).

They say Czechia changed its name for marketing. Moldova may not need a name change, but it could maybe use some rebranding. The state news agency is Moldpres and the phone company is Moldtelecom. Sounds vaguely unhygienic.

But on substance and politics, the three-and-a-half-year government of 52-year-old Maia Sandu in Chișinău, Moldova’s capital, is playing a shaky hand like a poker shark, navigating a small agrarian nation riven into parts toward the West, with many thanks to Russia’s war on Ukraine.

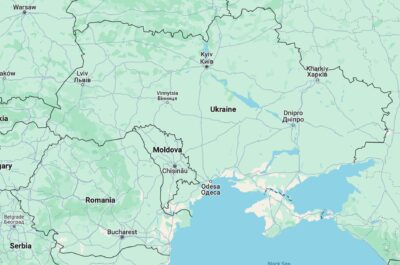

Moldova borders only Romania and Ukraine. Its fate is tied utterly to the war. To be clear right up front, I wanted to visit this summer because, depending on the outcome of the war, visiting later might not be possible, maybe for a long time.

Like everywhere else, Moldova’s electorate is divided. President Sandu’s pro-Russian predecessor Igor Dodon has been charged with all manner of crimes by all manner of authorities Moldovan and Western, crimes of high treason, corruption and racketeering. The U.S. Treasury has piled on with conspiracy charges. These charges have left Dodon effectively neutered as a political player for now.

Sandu’s most prominent current challenger, Ilan Shor, is only 37 years old. The former mayor of a Moldovan town of 20,000 called Orhei, Shor was convicted in 2017 in a fraud scheme that cost the country about a billion dollars, or 12% of its GDP at the time.

He fled the country and tends his eponymous Moldovan Shor Party from Moscow. Opponents call him “the leading political actor spearheading Russian actions aimed at derailing Moldova from its European course.”

There would be no need for politicians like Shor to operate from exile if President Putin’s war on Ukraine had gone to plan. Then, Russia would have driven through southern Ukraine to link up with a breakaway Moldovan region called Transnistria, seized the rest of the country and presented itself at Moldova’s Romanian border.

•

I wrote that Moldova is riven into parts. Let’s talk about them. The Moldovan heartland, the main and largest region, lies between the Prut and Dniester rivers, both meandering to the Black Sea. Once called Bessarabia, its governance flipped between Russia and Romania during the twentieth century and it speaks primarily Romanian. It comprises sixty percent of the country.

Transnistria is a small breakaway region that Mr. Putin uses to roil the rest of the country. It lies to the east of the Dniester River, in the narrow strip of land between the Dniester and Ukraine. People here are largely Russian language speakers and, with around half a million people, about twelve percent of Moldovans live there.

As the Soviet Union broke apart, independence wars erupted around its rim. Most Moldovans, like Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Georgians and all the way around the Stans, wanted to show their independence from the center in Moscow.

In a census prior to independence 65 percent of Moldovans were native speakers of Romanian (called ‘Moldovan,’ too), and 25 percent spoke Russian. By declaring the majority language to be Moldovan, the same language spoken by the Romanians to the west, revolutionary Moldovan leaders showed their colors. East of the Dniester River, where the predominant language is Russian, this freaked people out. With Russia’s encouragement, russophones there rose up.

It was a volatile time with conflict breaking out all around. Russia was in the throes of desperate humiliation at the loss of its empire, Putin’s “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.” As things fell apart, revanchists grasped at what they could.

With Moscow’s encouragement those inclined to grab a little bit of power cried persecution and declared their own republic, Transnistria. Thus was language used as a tool of division in Moldova, as it was elsewhere during the Soviet collapse.

(Language tests are still contentious matters in the former Soviet space. Since independence Estonia and Latvia have used language tests for citizenship, university admission, work visas and so on. Russia, naturally, views them as barriers for the Russian minority.)

Transnistria houses a Russian military base since an abortive takeover attempt following Moldova’s declaration of independence. Yet in unanticipated fallout from the war, everything has become more challenging for the Transnistrian rebels after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Because Transnistria had primarily been supplied by Russia through Ukraine and the war has closed that border, the only way out, even for the militant military types who tend the Russian garrison, is a humbling trip through the Chișinău airport.

With no escape except to the West, Tiraspol, the Transnistrian capital, has been forced into a modus vivendi with Chișinău. In the first half of this year more than 80% of Transnistrian exports end up in the European Union.

The internal Transnistria ‘border’ itself has become a perfunctory thing. Self-appointed Transnistrian authorities issue visas on a piece of paper, rather than a passport stamp. It shows how long you’re allowed on their side of the river. (Israel and Cuba, among other places, forego passport stamps too, as a way for visitors to bypass other countries’ sanctions.)

In a desperate shakedown for real money, Tiraspol issues local, not Russian, rubles, which are worthless everywhere else. You can’t spend Moldovan money there. Change what you’ll spend at the border.

And that Russian military base? It seems few of the soldiers there are actually Russian. Estimates vary, but one suggests that of about 1,300 soldiers, only 50-100 are Russian and the rest are locals who have been given Russian passports. It looks like their main task is to guard some 20,000 tons of Russian military equipment mostly dating from Moldovan independence, much of it unusable.

Thus tensions between Chișinău and Tiraspol have cooled for now.

There’s one more small and nominally autonomous primarily Russian speaking region called Gagauzia, not far south of the capital. With about 135,000 people, it’s led by a Putin confidant named Evghenia Guțul, formerly of Ilan Shor’s Shor Party and, like Shor, 37 years old.

According to Ms. Guțul, in a Moscow meeting this spring Putin “promised to extend support to Gagauzia and the Gagauz people in upholding our legal rights, our authority and positions in the international arena.”

She’ll appreciate Russian help. She complains of “illegal actions of Moldova’s authorities who are taking revenge on us for our civic positions and for standing by our national interests.” Meanwhile Moldova’s prosecutor general pursues legal action against her.

Without a lot of resources beyond a Putin acolyte for leader, Gagauzia’s raison d’etre looks like being a populist ethnic Turkish bastion, and otherwise little more than a Russian vehicle for undermining the Sandu government.

The thinking is that since a linkup with Transnistria is off the table for now, Russia’s Plan B now is to gain control politically through elections scheduled for the fall, using election fraud and agitation from Transnistria and the Gaugaz leader, This may be a thin reed. We’ll have to see. The Presidential election is October 20.

•

Moldova is not a big country. Chișinău to the Transnistrian capital Tiraspol would be 40 miles if you could fly; the “Zonǎ de Securitate” (has a certain Ceauceşcu ring, doesn’t it?) border post is an hour away via the R2 highway. Comrat, Gagausia’s capital, is scarcely fifty miles straight south past the Chișinău airport down the M3.

Moldova is not a wealthy country. The average monthly wage is something like $550. And with a considerable agricultural sector, the urban/rural divide is huge. Outside the capital region, farm workers live on around $220-$330 and probably engage in subsistence farming. In Chișinău professionals will earn much more, but even then, with your monthly $1600 or $1700, you will do well.

The capital region’s impact is huge nationally, generating about 60% of Moldova’s GDP. It’s because outside Chișinău and to a smaller extent Moldova’s northern second city of Balti and Comrat, Gaugazia’s capital, just about every livelihood is agriculture-based.

In Transnistria there is a steel plant, but sanctions and a mostly cold shoulder from Chișinău make it difficult for Moldova Steel Works to export its product. The only other notable industry centers around food processing and agricultural machinery, while there is some textile production. In Cahul, in the south, they can fruits and vegetables. There are no notable veins of coal or minerals for extraction.

Wine, though, is huge. About a dozen miles outside Chișinău, Mileştii Mici is a series of limestone caves 100 to 300 feet below ground known as the world’s largest wine cellar, and they say that there are 34 miles of wine storage – and a million and a half bottles – down there.

The loss of this breadbasket region hurt the Soviets just as the loss of Ukraine did. Fly in and you’ll see why. Farther west in Europe cities, towns and villages stretch across the horizon, but here the only thing is farmland, rolling hills, mile after mile of arable, productive land, seductive to a frozen northern capital like Moscow.

Chișinău itself presents as prosperous, in a low key way. Laid out on a grid, it spools over rolling hills, making it straightforward to find your way around. A handsome war monument stands over the national cemetery, the final resting place of countless Russian soldiers.

The government district, Sectorul Centru, perches atop a hill so that you can see a sprawling ring of suburban housing, and from there the city looks muscular, maybe bigger than it really is. Across the street from Government House, the neoclassical National Cathedral graces a prominent park that opens onto a leafy pedestrian promenade.

It has been a hot July in southern Europe. Temperatures hit 107 in Greece. Forty two of 52 weather stations in Cyprus reported records. Protests broke out in Krasnodar, southern Russia, because of heat related power outages. Chișinău started at 96 degrees with a promised 103 by the end of the week. A graceful park called Valea Morilor near the city center provided welcome leafy forest paths, and lots of shade.

•

Remember these two toilets in a single bathroom stall? They’re from the 2014 Sochi Olympics, for which lots of new facilities had to be built in a hurry. That construction project reflected the old Soviet work ethic, wherein “they pretended to pay us and we pretended to work.” That kind of Earth Two vibe is what made visiting the end of the Soviet Union so fascinating. If things didn’t fit together, nobody called a specialist; they just deployed a hammer.

The very nice downtown hotel we enjoyed in Chișinău had gorgeous, expensive cherry wood doors, and chandeliers full of missing light bulbs, and the entire hotel’s air conditioning was repeatedly overmatched by the heat. Here is an Earth Two Soviet artifact in that hotel; an overwrought, gilded – but frowning – TV table:

An over-presented, also gilded hotel breakfast room wailed a piano music version of ‘Fly Me to the Moon’ in a tight repeating loop, cocktail music at 8:00 a.m. three magnitudes louder than it was ever meant to be. Staff hovered alongside in horror of speaking English.

English isn’t Moldovans’ natural language. Historically it wasn’t even the second language you learn at school, that was Russian, so the young people who staff this hotel man the front lines of new language wars, their valiant battles disarming. The whole city has had to dive into English as a second language:

• Shine of the Hair.

• Casa del Tobaco

• Atrium Moldova Shopping Mall: SHOPPING, DISTRACȚIE, BUSINESS

Other Soviet-era remnants are disarming too: for two, the lack of a sense of danger and an utter lack of self-importance, of pretension. Of course there’s crime (certainly of the boardroom type), but as twilight descended on a Saturday night, central Chișinău felt like Red Square mid-1980s (overlaid with a little Latin languor), families and young people on promenade, flower ladies on street corners.

I can’t speak to how the atmosphere changes and how Chișinău feels past midnight on that Saturday night, but as darkness overtook the capital people thronged the sidewalks of Stefan cel Mare si Sfant Boulevard, where the Government House faces a Triumphal Arch that suggests the one in Bucharest.

•

Before visiting Moldova I imagined a hard barrier between war partisans, commerce sundered, trade and maybe communication interrupted between the with-us and against-us, whichever side you were on, right around the Black Sea littoral, an entire area riven by the war. I was thoroughly wrong.

Everyday life and trade roll right along around the Black Sea rim and across the conflict’s borders, war or no war. And why wouldn’t they? Chișinău’s thriving central market is packed with affordable stuff from all corners of the region and beyond. Turkish pop music wafts through and it helps to ground you in where you are in the world.

Landlocked Moldova’s restaurants serve fresh seafood from the Black Sea. In the Soviet Union Odesa, Ukraine, was a local place for Moldovans, just an hour down the road from the southern border. The war hasn’t stopped that.

A man named Marin, a company owner who’d left Kyiv the previous morning, told us he tended to some business in Odesa en route just got back to Chișinău. Four hours today, he said, Odesa to Chișinău, would have been only two without the border queue. In the other direction, he said, it’s slower, Ukraine examining paperwork at checkpoints.

“I never thought a war could start in 2022,” he said. But here we are, and life, and business, goes on.

Here’s how tangled up everything is: Russia still supplies breakaway Transnistria with natural gas. While at war with Russia, Ukraine allows Russian natural gas to cross its territory and taxes it. And part of the electricity in Moldova proper is generated by the big power plant in Transnistria, via that Russian gas.

•

With four more years of a Trump presidency, would Ukraine survive? And if not, would Moldova? That’s the stuff of another column, but consider that Moldova is a country of gentle rolling hills with no real physical barriers to attack.

Then consider the state of the Moldovan army: 6500 troops supplied with mostly Soviet era arms and fighting vehicles, augmented only by nineteen former Danish Piranha III armored personnel carriers purchased and donated by Germany in 2023, and about a hundred US armored Humvees.

The former Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt, among many others, worries that if supporters in the West “lose resolve, Europe may face a scenario where Russia subjugates the rest of Ukraine, installs a puppet regime, and gradually integrates most or all of the country into a new Russian empire.”

We have overestimated Russian capabilities before, but should that happen in a new Trump administration without NATO intervention, there is little to stop a revivified Russia, when it is ready, from rolling over a wholly under-equipped Moldovan force and right up to NATO’s Romanian border. For now the Sandu government looks secure in the coming fall elections, and is busy building bridges to the West. But Moldova’s future depends almost entirely on events to its east.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.