Editorial in Nature:

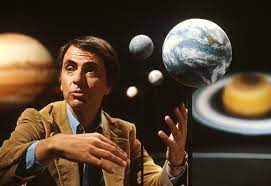

Early in 1993, a manuscript landed in the Nature offices announcing the results of an unusual — even audacious — experiment. The investigators, led by planetary scientist and broadcaster Carl Sagan, had searched for evidence of life on Earth that could be detected from space. The results, published 30 years ago this week, were “strongly suggestive” that the planet did indeed host life. “These observations constitute a control experiment for the search for extraterrestrial life by modern interplanetary spacecraft,” the team wrote (C. Sagan et al. Nature 365, 715–721; 1993).

Early in 1993, a manuscript landed in the Nature offices announcing the results of an unusual — even audacious — experiment. The investigators, led by planetary scientist and broadcaster Carl Sagan, had searched for evidence of life on Earth that could be detected from space. The results, published 30 years ago this week, were “strongly suggestive” that the planet did indeed host life. “These observations constitute a control experiment for the search for extraterrestrial life by modern interplanetary spacecraft,” the team wrote (C. Sagan et al. Nature 365, 715–721; 1993).

The experiment was a master stroke. In 1989, NASA’s Galileo spacecraft had launched on a mission to orbit Jupiter, where it was scheduled to arrive in 1995. Sagan and his colleagues wondered whether Galileo would find definitive evidence of life back home if its instruments could be trained on Earth. They persuaded NASA to do just that as the craft flew past the home planet in 1990.

As we describe in an essay, a big concern for the journal’s editors was that the paper did not report a new finding. Nature published it because it was a convincing control experiment to test the accuracy and relevance of the methods being used to detect extraterrestrial life. Had the study found less evidence of life than it did, that would have been even more significant — it would have called into question the relevance of the parameters that scientists proposed as evidence of life on other worlds.

More here.