Alexandra Jacobs in The New York Times:

We could all use a hype man like George Henry Lewes.

We could all use a hype man like George Henry Lewes.

George Henry Who’s?

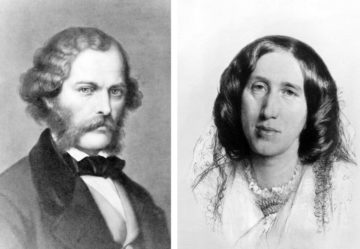

Well, exactly. A “littérateur, physiologist and metaphysician,” as an obituary in The New York Times called him in 1878, Lewes is today most remembered as the longtime romantic partner and de facto agent of George Eliot: author of works consistently ranked among the best of Victorian literature — perhaps all of English literature. “A novel without weakness” was how the generally unsparing Martin Amis assessed her “Middlemarch,” the mistress-piece to which Rebecca Mead, a writer for The New Yorker, devoted an entire memoir.

For yes, in case you’ve been living under a giant rockery, George Eliot was a “her,” with several roles other than her nom de plume: daughter, sister, friend, wife, stepmother. There have been a gazillion biographies of the great woman, starting with the one assembled by her only legal, late-in-life husband, John Cross (who was 20 years younger and notoriously attempted suicide on their honeymoon, flinging himself into the Grand Canal of Venice from a balcony and getting fished out by a gondolier and hotel employee).

“The Marriage Question,” a careful but impassioned new book by Clare Carlisle, a philosophy professor who edited Eliot’s translation of Spinoza’s “Ethics,” is different in its close focus on an idea: that the titular institution shaped Eliot’s identity and work — and has some affinity with Carlisle’s own current undertaking. “Perhaps a biographer’s devotion is a little like the devotion of a spouse,” she observes, in an especially apt analogy for this noble but sometimes plodding literary endeavor. “Writing a person’s life means living with them intimately, struggling to understand them, wondering how far they can be trusted, dealing with the ways they resist, annoy, disappoint, challenge and elude you.”

More here.