by Barbara Fischkin

Again, I thought about changing my name.

I dreamed about publishing essays under a new byline. I tried out pseudonyms for my next book. I wrote down alternate names, said them out loud. A name change would make introductions easier. Now, when I extend my hand and say “Fischkin,” people look at me funny, as if I might be holding live bait.

I can live with Barbara. As a first name, it is dated. But Barbara will come back in style. First names do. I was almost named Benita. Benita Fischkin. Think of that. My mother loved that name, until a friend said a cute nickname for me could be Mussa—close enough to Mussolini.

That was all my mother Ida Siegel Fischkin had to hear. She was a passionate supporter of the State of Israel, a lifetime Hadassah member and a child survivor of an antisemitic pogrom. Benita went down the drain. As a little girl, bored with Barbara—too easy to spell—I asked my mother if she had ever wanted to name me something else.

“Benita,” she said. My mother hid little from me.

Wow, I thought, wishing she had gone through with it. A name like that dripped with fame, fortune and beauty.

Benita as a baby name for a newborn girl must have been making the rounds of pregnant mothers in our Brooklyn neighborhood, circa 1954. Very odd since this was less than a decade after World War II. My guess: When it came to villains, Hitler was the main event. I bet no one ever said: “For a boy, how about Adolph?”

The mother of one of my classmates did name her daughter Benita. Benita asked us to call her “Bunnie.”

Back to the real problem. Fischkin. It has other strikes against it. Fischkin is not melodic. In my case it also has that annoying extra letter, the “c.” People want to spell Fischkin as Fishkin. Most Fishkins are Fishkins not Fischkins.

It does make it easier for me to be found on Google. A mixed blessing.

It all comes back to that ghost. Fischkin evokes the name of my paternal grandfather, who died long before I was born. He was a drunk and a womanizer. He beat his wife and children. Today he also would be called a “Deadbeat Dad,” which he was on occasion. I know all this because relatives did speak about him. But only in hushed tones and without mentioning his first name, as if mentioning it would bring on a curse. I am still not sure of his name. Phillip, maybe. What was he called before Ellis Island? Your guess is as good as mine. And, no, I do not want to explore this on ancestry.com.

I do know that my grandfather was Fishkin not Fischkin. My father added the “c,” to his name as a young man. His siblings did not. They remained Fishkins. My father, often a great parent despite his own upbringing, told me he did this to disassociate himself from that father of his. He said adding the “c,” made him feel like a rebel.

Laugh, if you will. Even as a child I thought this was a hoot. My father had a boring job as a civil service accountant. He wore white shirts to work, short sleeve white shirts in the summers before office air-conditioning. Not that he was a milquetoast. Or that everything was rosy and nothing was weird. He asked my mother to put covers fashioned out of paper bags on the regulation paperback mysteries he read on the subway. He did not like other people to know what he was reading, no matter how benign. He had opinions. He had a temper. He yelled at my mother, his in-laws and my older brother although rarely at me, the princess. His yelling scared me. I came to believe it had roots deep inside him, old roots.

At home, we chuckled when my father came home from the shul and said he had yelled at the rabbi. Again? For decades he served as the congregation’s president, working with the rabbi as they yelled at one another.

Still, in my young mind rebels did not work for the City of New York or lead the board of trustees of Congregation B’nai Israel of Midwood. They wore leather jackets and drove motorcycles. As a college student I tried to convince myself that adding a letter to one’s name could be an act of peaceful civil disobedience. I tried to view my father David Fischkin as a major hero, like Mahatma Gandhi. I couldn’t.

I am particularly haunted by the sound of Fischkin, when I compare my name to those of other writers. So many of my writer friends have beautiful names. Ana Menéndez, Roxana Robinson, Terese Svoboda to name a few. Their names roll off the tongue in a way that Fischkin never could.

To assuage myself, I have looked up the meaning of Fischkin. I found one nice definition that claimed Fishkin—couldn’t find Fischkin— is not related to fish but rather to a word meaning “life.” Nice, if true but too long to explain upon offering a (clean) handshake.

There is, of course, the easy solution. I could be Barbara Mulvaney. I have, in effect, been Barbara Mulvaney for 39 years, since I married Jim Mulvaney. My grown children are Mulvaneys. Barbara Mulvaney would be a beautiful byline—and a recently redeemed one now that Trumpster Mick Mulvaney is out of the picture. But if I didn’t become Barbara Mulvaney when I got married, why do it now? At the beginning of our marriage, I was a newspaper reporter with my own byline. Barbara Fischkin. Professionally I wanted to be known as myself. Not as my husband’s wife. That we reported for the same newspaper intensified my resolve. But even now, as we each write in different realms, I feel the same. Or at least I think I do.

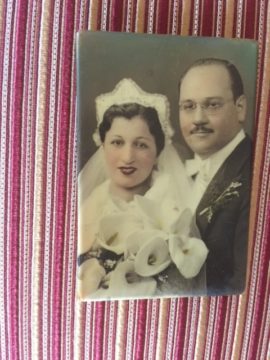

If anyone has ever published anything about my father’s side of the family, I have not seen it. As the only mainstream author among the Fischkins, I am the one most likely to do this. I have not written about my father’s relatives because the story of my mother’s side of the family, the Siegels—which inspired the historical novel I am writing—is so much more exciting. Despite war and mayhem, it is also less dreary. My Siegel grandparents, aunts and uncles and my brother died of natural causes in their sixties, seventies, eighties and nineties. My three first cousins and I remain close. Each of us knows the family history, as if the stories that make it whole are flesh, blood and bones. My mother—she of the great “Benita” idea—is typically the star of these tales. In 1919, at the age of six my mother saved her own life in the midst of that pogrom. She ran from a burning building into the countryside and hid in a haystack. A local farmer, who was not Jewish and perhaps a Ukrainian Nationalist, found her and hid her, risking his own life to save hers. Not that my Siegel aunts and one uncle were slouches when it comes to legend. Aunt Doris dressed like a flapper and yearned to dance on a Catskills hotel stage. Uncle Sammy, as a kid in Brooklyn, got shot in the leg (probably by local gang members) and later returned to the Europe of the pogrom he had also survived to fight the invading Nazis. Aunt Mollie was the first of her immediate family born in America and that should be enough, although there is so much more to tell about her.

Yes, I have wondered about changing my name to Barbara Siegel.

My father had no uplifting tales like these about his family. When he met my mother he married her—and her family. For the warmth and for the stories.

It was on a rainy day in June that I began this year’s musings about changing my name. In July I threw the idea out the window to melt in the hot summer air. When I backtrack like this, there are always triggers. Triggers apart from the weather.

My change of heart started with the arrival of the Summer 2023 print edition of PaknTreger, the multi-faceted magazine of the Yiddish Book Center. It had an article about deadbeat Dads of yore: A Gallery of Missing Husbands by Michael Morgenstern. He writes: “Thousands of Jewish men who trekked overseas either failed to send for their families or disappeared once the whole family was resettled. They often did this without warning, leaving wives and children in dire distress. The first significant effort to alleviate this crisis did not come from a social service or government agency but from the New York-based, Forward, a rising Yiddish newspaper that was then barely a decade old.”

My Siegel grandparents loved the Forward, as I love today’s English version. PaknTreger were book peddlers who wandered the Eastern European shtetls. I read the PaknTreger article, a compilation of notices and pleas often contributed by the long-suffering wives, themselves, as if it was news, delivered to me by one of those peddlers. I devoured the stories of men, men sort of like my grandfather. It was akin to seeing Hester Street in multiple variations. I wondered if my grandfather’s photo had ever appeared in the Forward. The timing was right, and those missing husbands sounded a lot like the little I knew about him.

Reading about those men also sent me back to an informal memoir my father had started to write after his retirement. He wrote it in his neat half print, half cursive on unused sheets of his accountant letterheads. I had not looked at my father’s pages in years but do remember brushing them off as “not enough information.” Nothing about the added letter “c.” There was a lot about my grandfather and yet not enough. My father never mentioned his name.

My father died three years after he started to write this, never finished it and the end is slapdash. But I now see it contains gems.

A sample: “We were living on Osborn Street in Brownsville, even then a rapidly decaying slum street. There were two small frame houses. We, of course, lived in the worst of the two, the one in the backyard. One night about 2:30 am a fire broke out in the front house. Mother, my two younger brothers and myself went quickly into the street. My father was nowhere around. Not home. Probably drinking or whoring somewhere. We walked the streets until daylight. No one cared. No one took us in. We were cold, shivering and miserable. I never forgot this and I became cynical and unfriendly to other people.”

Another sample from my father about his: “My father cut a wide swath with wine, women and song.”

And then this about my grandfather’s background, which may or may not be true. “He was a landsman of General Sarnoff [who ran RCA, among other accomplishments]. But never met him to my knowledge in New York. Two Jewish-Russian boys and how different they turned out to be!” My father added that his father was a pressman and “a member of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union but a follower never a leader.”

From this I was at least able to discern that my grandfather must have come to Brooklyn in the early years of the twentieth century from a small town near Minsk, now the capital of Belarus. The town might have been called Uzlian, now Uzlyany. Well, that is where David Sarnoff came from, why not my grandfather as well?

My father’s writings came out of a drawer in my home office that also contains my mother’s memory book. As I was reading what my father wrote, a piece of paper slipped out of my mother’s book, like a nudge. The paper was a narrow sheet with red lines, from a stenographer’s notebook. In the early days of her marriage my mother worked as secretary. Years later my husband and I, like most newspaper reporters, used the same sort of notebooks.

This single page was folded in half.

On the top half in my father’s distinctive dual handwriting: “Private Communique!” On the crease and beyond to the other side: “For Mrs. Ida Fischkin only!! (turn over).

Inside was this:

Intra House Memorandum 10/21/40

From: David Fischkin

To: Mrs. Ida Fischkin

Please consider this memorandum as your authority to awaken, upon your arrival, the newest, lowest salaried Assistant Manager of the City of New York. Don’t be bashful. Although gruff, dry-witted and sharp tongued, the new Assistant Manager is honest, fair and sincere. To be truthful, he would rather be awakened and see you than to receive the glory and acclaim of his new position.

Yes, my father liked to take naps. He liked to play with words. I think that most of all, apart from his wife, children and adopted Siegel family, he liked the name Fischkin with a “c.” After I read this “private communique,” I remembered that my father watched my first television “appearance,” as a Newsday reporter interviewing Patrick Vecchio, a Long Island Town Supervisor on the regional show: Meet the Mayors. A far cry from Meet the Press. That did not matter to my father. He told me that “seeing the Fischkin name on the television screen was the happiest day of my life.” (Yes, Channel 13, WNET, the New York City public television station, had spelled it correctly.)

And so, at this moment I am still Barbara Fischkin. Unless I (finally) become Barbara Mulvaney. My husband has also written me beautiful letters, which I treasure. I hope as I write more about my mother and her family, I also will start to write more about my father and his demons. I remember my father well, even with the specter of my grandfather behind him. As for my grandfather, I imagine him removing the “c” and then skipping town.

***

Barbara Fischkin’s website can be found here.