by Marie Snyder

He received the Order of Canada, profoundly helped many people with addiction on the streets of Vancouver, and is much loved and admired, but some of Dr. Gabor Maté’s claims feel like they don’t hold water. And some claims might actually be dangerous if blindly accepted.

He received the Order of Canada, profoundly helped many people with addiction on the streets of Vancouver, and is much loved and admired, but some of Dr. Gabor Maté’s claims feel like they don’t hold water. And some claims might actually be dangerous if blindly accepted.

I’ve encountered Maté in a few courses I’m taking, and have been strongly encouraged to watch his newest film and read his book several times now; I opted for the former. One follower was excited to tell me, with great confidence, that ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease) is caused by a specific trauma and that everyone is carrying unresolved trauma which, if resolved, can heal physical ailments like cancer.

I’m dubious. I have some reservations that I’ve kept to myself until seeing so many in academia wholeheartedly promoting some poorly substantiated claims.

While Maté has some excellent techniques in the work he does, the way he presents and explains the material provokes me to look up research studies to try to corroborate many of his ideas.

I gobbled up his books twenty years ago, and there are some useful analogies and treatments in there, but even then there were parts that gave me pause.

In Scattered Minds, he concludes that every child with ADHD experienced a trauma, and all their ineffective brain processing is due to a troubled core relationship: “Every child with ADD has been wounded by a disruption in the relationship between the caregiver and the sensitive infant.” This is not significantly dissimilar from the old claim that “refrigerator moms” cause autism, and it appears to ignore all the studies on the ADHD brain that tell a different story. Studies have found specific neurological differences in people with ASD as well. Maté followers might insist that the early years caused those brain differences, but can we take a minute to consider that it’s possible that people are born this way? Or that genetics is part of the picture? It’s curious that this possibility feels like it’s being completely tossed to the curb as a barrier to healing (overlooking the financial barrier to accessing therapy). He implies that there’s nothing different with the brain from birth; any issues were caused by parenting and, therefore, can be corrected with therapy. It’s an extreme epigenetic stance that the brain is a blank slate entirely created by childhood.

In Scattered Minds, he concludes that every child with ADHD experienced a trauma, and all their ineffective brain processing is due to a troubled core relationship: “Every child with ADD has been wounded by a disruption in the relationship between the caregiver and the sensitive infant.” This is not significantly dissimilar from the old claim that “refrigerator moms” cause autism, and it appears to ignore all the studies on the ADHD brain that tell a different story. Studies have found specific neurological differences in people with ASD as well. Maté followers might insist that the early years caused those brain differences, but can we take a minute to consider that it’s possible that people are born this way? Or that genetics is part of the picture? It’s curious that this possibility feels like it’s being completely tossed to the curb as a barrier to healing (overlooking the financial barrier to accessing therapy). He implies that there’s nothing different with the brain from birth; any issues were caused by parenting and, therefore, can be corrected with therapy. It’s an extreme epigenetic stance that the brain is a blank slate entirely created by childhood.

A study on ADHD, found “the direct effect of Childhood Trauma on total ADHD symptoms fell short of reaching statistical significance.” They could show an association with childhood traumatic events, but recognized that it could be bi-directional, as children with ADHD may be, “prone to experiencing Childhood Trauma such as aggression or abuse, because they tend to act out more and/or because of their family members might show problems with impulse control themselves (ADHD has a strong genetic basis).” This is the more nuanced and in-depth view that I would expect from someone of Maté’s reputation.

Then in When the Body Says ‘No’ he furthers this nurture-essentialism about cancer being caused by a repression of anger: “For lung cancer to occur, tobacco alone is not enough: emotional repression must somehow potentiate the effects of smoke damage on the body.” The study he cites gave a psych assessment to 1,353 people, then looked at the 619 people who died within ten years, and found the 38 people who died of lung cancer all smoked and all scored high on repression of anger. The study concludes that there’s a correlation between lung cancer and suppressed rage, but Maté goes on to suggest buried emotions led to cancer, implying a causal relationship, instead of exploring the potential confounds. It makes sense that someone with rage might turn to cigarettes to self-medicate, so the two things, smoking and suppression, could be connected, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that it’s the emotional experiences leading to lung cancer.

Then in When the Body Says ‘No’ he furthers this nurture-essentialism about cancer being caused by a repression of anger: “For lung cancer to occur, tobacco alone is not enough: emotional repression must somehow potentiate the effects of smoke damage on the body.” The study he cites gave a psych assessment to 1,353 people, then looked at the 619 people who died within ten years, and found the 38 people who died of lung cancer all smoked and all scored high on repression of anger. The study concludes that there’s a correlation between lung cancer and suppressed rage, but Maté goes on to suggest buried emotions led to cancer, implying a causal relationship, instead of exploring the potential confounds. It makes sense that someone with rage might turn to cigarettes to self-medicate, so the two things, smoking and suppression, could be connected, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that it’s the emotional experiences leading to lung cancer.

It’s similar to an old study in the 80s that showed a clear correlation between the amount of violent TV watched at age 8 and the criminality of people at age 18. Some people reacted by trying to ban any violence in shows shown. But even though there’s a strong correlation, there are other confounds in the way that could cause both of these things to happen. It could be a matter that kids who were neglected by parents at 8 watched a lot of unsupervised and also became criminals, with neglect the primary cause. Or it could be that the 8-year-old with an inborn predisposition towards enjoyment of violence watched more, with their biology the primary cause of later criminality. Or it could be something else entirely, and it’s likely a mix of things.

You can see where this is going. Just because 38 people with fatal lung cancer had anger repression doesn’t mean the anger caused their cancer. And it really doesn’t mean that resolving anger issues will prevent or cure cancer. To be clear, it’s not a bad idea to resolve any anger issues anyway, but we need to temper our expectations around what therapy can actually do.

People are far too complex for it ever to be all one thing that causes change. Maté is banking on trauma being the one. Flip that one switch, and we’ll all be healthy and productive.

Another example: Maté states that “Research has suggested for decades that women are more prone to develop breast cancer if their childhoods were characterized by emotional disconnection from their parents or other disturbances in their upbringing.” That study found a correlation but concludes, by contrast, “Although there can be little doubt that a subtle relationship exists between loss and depression and the clinical onset or exacerbation of cancer, the question still remains whether some persons are more vulnerable than others because of their idiosyncratic way of responding to, or coping with, depression.” Much more recently, cancer research organizations indicate that there is no evidence that stress has a direct effect on cancer.

Later Maté explains that “rheumatoid diseases is a stoicism carried to an extreme degree, a deeply ingrained reticence about seeking help” adding arthritis to the list.

So, what does it matter that there are different perspectives on how stress affects our physical health??

Maté’s stance takes people and governments off the hook for adverse health conditions, and puts it all at the feet of our earliest caregivers. You didn’t get cancer from smoking or living with polluted air, but because of your upbringing, but understand that your caregivers also were affected by their own childhoods, so don’t be too hard on them either. And really, it’s nobody’s fault.

Most dangerously, it could lead people to spend their money on expensive therapies, like the ayahuasca trip Maté promotes, instead of ALS or cancer treatment.

To be clear once more, I agree that our brain is affected by our earliest years and continues to be affected throughout our lives, changing neural pathways as we change the way we think about things, but that’s very different than changing entire sections of the brain, consistently, with each person with similar symptoms or with giving people cancer.

I understand why he sells so many books. If we believe there’s no genetic or structural component to our problems, that our brains started out perfect and were altered in childhood, then we can fix them!! With a little therapy, we can get ourselves back to this perfect state free from cancer, arthritis, and ADHD. That sounds amazing!! And it makes sense that a program training psychotherapists might favour this position. It’s really good for business! (And there might be a bit of a God complex in the mix if they believe therapy is a cure-all.)

The Maté video that was part of my curriculum this year was about understanding addiction as a result of trauma. Similar to prior claims, this time addiction is due to the emotional states of the mother both pre-verbally and neonatally. Since 100% of females with addiction had sexual abuse in their background, it is suggested that trauma causes addiction. I don’t disagree that trauma can provoke addiction, but I haven’t seen evidence from him that it’s not possible to be an addict without having suffered trauma. He’s making an error of confirming the consequent. It’s like saying, since 100% of professors went to kindergarten, therefore kindergarten causes people to become professors.

To really show a kindergarten-professor connection, we would need to find a random sample of a couple thousand people who went to kindergarten and see how many became professors and compare them to a couple thousand people who did not go to kindergarten. Similarly to show an abuse-addiction connection, we need to find a random sample of a couple thousand people who have been abused as children, and look at how many have addiction issues, and compare that to a couple thousand people who were not abused as children.

Instead, Maté’s proof is to do a parlour trick: He calls up someone from the audience with addiction issues, and succeeds, in three minutes, to dig deeply enough to find some traumatic childhood memory.

But, wait a minute. Elsewhere he says that we’ve all been traumatized in childhood, so shouldn’t we all be addicts??

One of the criteria of “trauma” in his demonstration was “loud voices” in childhood. Since this behaviour is relatively common in all families, I am left searching for his falsifiability criterion of “traumatic childhood.” What does a non-traumatic childhood look like? Even if he were to show a correlation between parents yelling and addiction, then that does not prove causation. It is similar to doing his three-minute challenge on everyone in the audience wearing white socks, and then, when the majority reports some traumatic childhood incident, insisting on a causal relationship between the two variables.

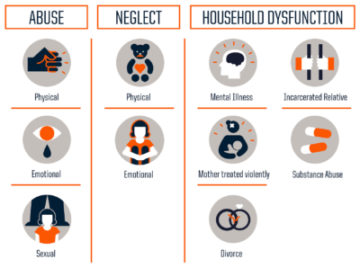

Here’s the thing: There has been a study that found a clear correlation between the amount of negative events in childhood and addictive behaviours in adulthood. They gave people an ACE-Q test that asks them about the Adverse Childhood Experiences: physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, physical and emotional neglect, and any household dysfunction that include a family member with mental illness, incarceration, domestic violence, substance abuse, and divorce. Add up the scores out of 10, and they found a direct correlation: “the odds of illicit drug use and addiction increases with the number of positive ACE categories.” Their questionnaire does not include yelling as a form of trauma.

However, the study doesn’t take the extreme view that Maté takes. It acknowledges the limitations of the ACE test, that participants self-report frequency (“often or very often”) of these events so being grabbed roughly a few times counts as much as being regularly beaten. It also doesn’t ask about the positive events in childhood that could help to foster coping skills. Furthermore, even with a correlation, it’s entirely possible that people with troubled backgrounds don’t have addiction issues, and many with loving childhoods not marred by trauma do, because it’s complicated. There are many causes. I completely agree that abuse in childhood is one factor, but I disagree that it’s necessary or sufficient to produce addiction.

| According to Maté… | These People Exist | These People Do NOT Exist |

| High ACE score | addicts of all kinds | not addicted to anything |

| Low ACE score | not addicted to anything | addicts of any kind |

Dr. Stanton Peele explains another problem with Maté’s claims about addiction and trauma: “It is not enough to say that this model is highly conjectural. It also isn’t true, that is, it makes little sense of the data. . . . Only a tiny group (3.5%) of people with four or more adverse childhood experiences became involved in injection drug use. So Maté’s model is highly undiscriminating.” Drinking is similar, with just 16% with high ACE scores having any alcohol dependency. Peele’s concern: “Rather than expand our understanding of addiction, his views harm our ability to respond to it. . . . diverting the addiction field from a more comprehensive and practicable view of addiction.” He’s also skeptical that, if trauma isn’t apparent, Maté will go looking for it, “in which case it will always be found, or else made up.” James Coyne further scrutinizes his claims more colourfully: “Maté urges us to abandon what has evolved over time to be evidence-based solutions to health and social problems [for] perhaps interminable therapy to exorcise the demons.”

It’s very plausible that child abuse leads to addiction, absolutely, but it’s not necessarily the case, and, more importantly, it’s not the only element. Genetics and parental coping behaviours modelled to children might both be more highly correlated than an adverse childhood experience.

Maté also argues that Oppositional Defiance Disorder (ODD) is entirely a North American phenomenon from pathologizing normal childhood behaviour; it’s just a child pushing back on a parent. He argues that since ODD only appears in the company of others, and disappears when the child is alone, then it doesn’t exist. However, from this logic, conditions like borderline personality disorder, narcissism, and level 1 ASD also do not exist since their main symptoms only appear in relation to other people. I have worked with teens with ODD, and, anecdotally, they appear to operate significantly differently from their peers in how they assess and react to their environment. It is not a matter of just pushing back on demands since they will argue against any random statement or request even against things they want to happen. They are contrary by nature. It is a difficult condition to work with, and it does a huge disservice to parents, caretakers, educators, and people with the disorder to insist it is a figment of the imagination of North Americans. And, of course, ODD is seen at similar rates in European studies.

The most nefarious perspective: some suggest that these types of mind-cures are to get people to,

“internalize their failures. It’s to get them believing they don’t need medicine. It’s to get them to police each other for dissent and to reinforce and normalize passive behavior. It’s to make the exploitation go down a little smoother. . . . Your typical self-help seminar operates the exact same way that Phineas Quimby did almost 200 years ago. The guru stands in the middle of a giant crowd. They have people stand up and describe their problems. The guru diagnoses them on the spot. They come up with a convincing story, something that sounds good. They give them homework. The patient goes through some kind of catharsis, mainly because it’s the first time anyone ever bothered to listen to them. Simply by the law of averages, some people will manage to pull themselves together.”

That sounds very familiar.

It’s a quick fix to finding your perfect healthy self. Find the right therapist and you’ll be amazing. But that’s just not true. The reality is, a therapist can help, but they won’t be your saviour that washes off the detritus to find the most perfect version of you inside. We will always have to struggle to find meaning and resolve our issues and think for ourselves and that is a lot of work. People are messy. And we will get sick in ways that therapy has nothing to do with, so we have to fight for access to quality medical care and medication. And many of us think differently (ADHD/ASD), which could be helped more if it were accepted as a difference rather than considered the unfortunate result of childhood trauma. It wasn’t all your mum’s doing. It just is what it is.

But he definitely has some good mixed in with the outrageous claims. For instance, “Children don’t get traumatized because they got hurt. Children get traumatized because they’re alone with the hurt.” Be there for your kids or for anyone who needs a listening ear. Let’s be there for each other, for sure. That’s the best we can realistically do.